Halting the Hemorrhaging of the Jewish People

We need solutions to make Judaism appealing in an open, assimilated world.

There is a story about two cousins: Czar Nicholas of Russia and Emperor Franz Joseph of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Late in the 19th century the czar went to Vienna for a visit. He was struck by the relative freedom, at least economic, that Jews enjoyed in that city.

When the two cousins met, Nicholas chastised his cousin: “Franz, haven’t we agreed that we will destroy the Jews? Look what I have done. I force them to live in isolation in the Pale. I do not permit them to travel, to get an education or to enter meaningful occupations. You, on the other hand, give them economic opportunities. They become owners of great businesses, and, of course, they attend university and become professionals.”

Franz Joseph responded, “Cousin, you destroy them your way, and I’ll do it my way.”

Get The AJT Newsletter by email and never miss our top stories Free Sign Up

Was Franz Joseph right?

It seems that 2,000 years of anti-Judaism in the Christian world could not destroy us. To the contrary, imposed isolation — whether in the Ghetto Nuevo in Venice, the various German ghettos or Russia’s Pale of Settlement — kept us alive spiritually and prevented assimilation into the Christian culture.

But two historical changes have offered Jews paths to integrate into Christian culture, a trend that increases in spite of the Holocaust: the breakdown of isolation and increased educational opportunities.

As late as 1943, when I and all Jews in Munkacs were taken to the German camps, most Jews lived, more or less, isolated from the Christian community.

I lived on a street that was completely Jewish with the exception of one family. At the age of 6 or younger, I would leave our Shabbat table and visit a neighbor because, as I told my mother, the cholent or kugel was better than hers. I just had to appear at the neighbor’s home, and a place was made for me.

I went to a parochial school where the language of instruction was Hebrew, and all the students were Jews. My parents didn’t have to worry about intermarriage because I didn’t have a chance to interact with non-Jewish girls and the Christian girls didn’t have the opportunity to develop sentimental relationships with Jewish boys. The separation between the religions was a fact of life.

Maintaining ourselves as Jews in a society that encouraged our isolation was easy. The difficulty arose when we achieved freedom and our imposed isolation eroded.

In the major European cities, this change began with the Enlightenment and the French Revolution ideals of liberty, equality and fraternity, as spread by Napoleon.

When the walls of the ghettos began to crumble and our interreligious association increased, we were stuck on the horns of a dilemma. On the one hand, we desired this new freedom; on the other hand, how could we keep Jews from intermarriage and conversion?

Once we could live where we chose, interreligious interaction became more frequent. Take the case of Rabbi Moses Mendelssohn, the father of the Jewish enlightenment. His closest friend was Gotthold Ephraim Lessing, who portrayed the rabbi in his famous book “Nathan the Wise.”

The synagogues and Jewish houses of study were not equipped to overcome the consequences of friendly interaction. One of the first sociological laws is that interaction varies with sentiment; in other words, the more one interacts with another, the more likely it is that sentiment will develop between the two.

To prevent interaction and the development of positive sentiments that encourage assimilation, we would need to revert to isolation, which most Jews would refuse.

Jewish integration into the Christian world also was enhanced by the rise of ideals that advocate rationality and secularization. Both of those perspectives in a short time became part of the Jewish intellectual world, and, together with positivism, a new philosophical movement led to a commitment to a rational, fact-based interpretation of the Torah and Talmud.

These new perspectives brought a demand for the reinterpretation of Judaism and a rejection of the notion that the sacred mitzvot were G-d-given; instead, they could be understood as a function of social needs.

Positivism also led to the rejection of the ancient belief that G-d gave the Torah on Mount Sinai, a perspective that was rooted in naaseh v’nishmah (we shall do, and we shall listen) and demanded obedience to the Torah and rabbinical laws.

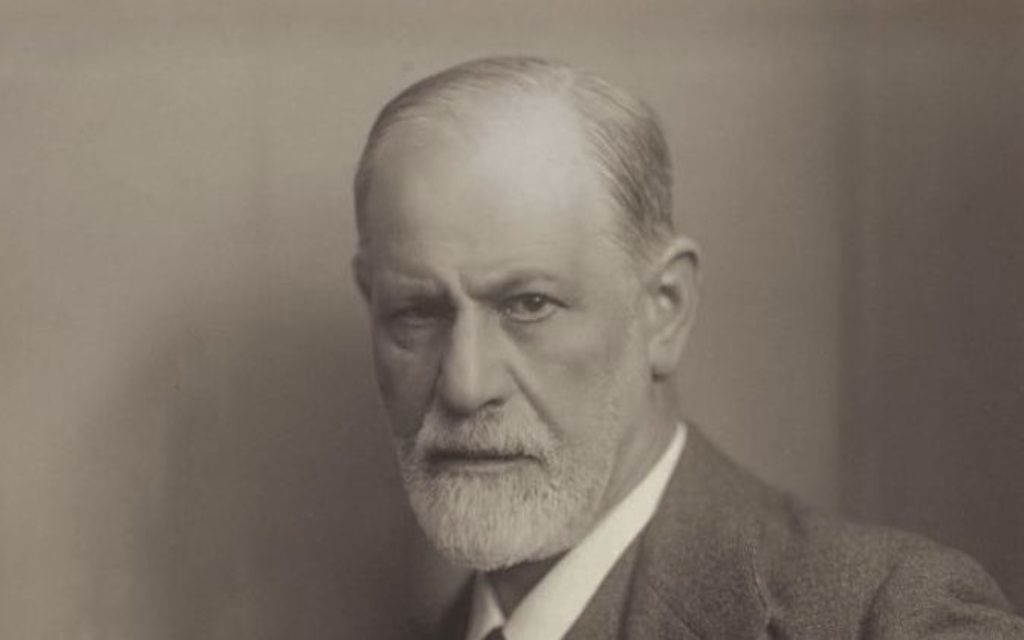

The Enlightenment brought a rejection of unquestioned obedience and supported the critical examination of religion from a rational perspective. This new perspective influenced Freud, Einstein, and writers such as Kafka and Zweig. No wonder that Peter Gay’s biography of Freud is titled “A Godless Jew.”

Freud and Einstein maintained their Jewish identity, but it was an identity without faith or adherence to beliefs and laws dictated by Judaism as a religion.

My wife was a member of the Atlanta Lawn Tennis Association, where the majority of her teammates were Christians. They asked her the reason for kashrut. She gave them a rational explanation, then in vogue, that kosher laws were based on an early perspective of the relationship between food and health.

Later, she asked me whether her response reflected the true reason for food laws. I told her that the reason for kashrut is unknown and that those who adhere to it do so because they believe that G-d ordained it. Such a response, of course, would have violated all tenets of rationality.

I have heard various explanations, such as “We don’t eat pork because of the danger of trichinosis,” which isn’t true. Trichinosis was an unknown disease 3,000 years ago.

I have also read a rational explanation given by an Orthodox physician for using the mikvah after menses; according to him, it is for health reasons. This physician related the use of the mikvah to the relative absence of uterine cancer among Jewish women.

Like Freud, many Jews who gave up their religious identity because of its demand for belief in nonrational explanations still wished to keep their Jewish identity, especially in Germany. This was true among Zionists who centered their identity in history rather than religion, especially among socialists, such as the Hashomer Hatzair.

There also were the Yiddish Bundists, whose Jewish identity was placed in a commitment to culture.

With the advent of Hitler and the Holocaust, all such issues disappeared for a while, only to reappear in the United States some years after World War II.

The latest report based on the Pew Study shows that the United States has 2½ million Jews who reject religion and substitute an ethnic- or cultural-based Jewish identity.

Reporting on this phenomenon, demographer and sociologist Steven Cohen suggested that this is a growing phenomenon among Jews. Secularization, the substitution of a rational explanation of life for one based on religious beliefs, is increasing not only among Jews, but also among Christians.

The reason is increased education. Changes toward religion in general and among Jews in particular were enhanced by tremendous increases in the percentage of Americans attending colleges and universities — a function of the GI Bill that connected with a high commitment to education among Jews.

The increase of education led to revolutionary changes related to race, sex and gender, as well as a stronger commitment to rationality.

The number of Jews who will seek a Jewish identity outside religion will continue to increase and may even invade the Orthodox community as they permit their children to attend non-Jewish schools of higher education. Can we afford to lose that many Jews from our community?

The issue all Jewish communities must face: Is there a way by which we can reintegrate these Jews into our community? Can we find new ways to be Jewish without religion?

Perhaps we need to heed Isaiah Berlin, who proposed more than 50 years ago that Jews will seek a historical identity based on our worldview of morals and freedom rather of traditional faith.

An interesting phenomenon reported by the Pew Study is that the number of Jews, including non-religious Jews, who participate in the Passover seder remains high. Why? Perhaps because this holiday’s historical message reflects the Jewish consciousness of a commitment to liberty — to a universal moral concept of personal and collective freedom.

Let me direct the following to the rabbis of liberal Judaism. Perhaps we need to begin with Reform temples — institutions that proclaim themselves to be liberal — to open their facilities and under their auspices reintegrate the historical-cultural Jews into our communities and thereby stop the loss of Jews from our midst.

Perhaps quasi-services consisting of music, history and the examination of the development of morals will bring them back and reintegrate those whom the PEW report refers to as Jews without religion into the Jewish collective.

comments