‘Wild Nights’ Awakens Us to Sleep Nightmare

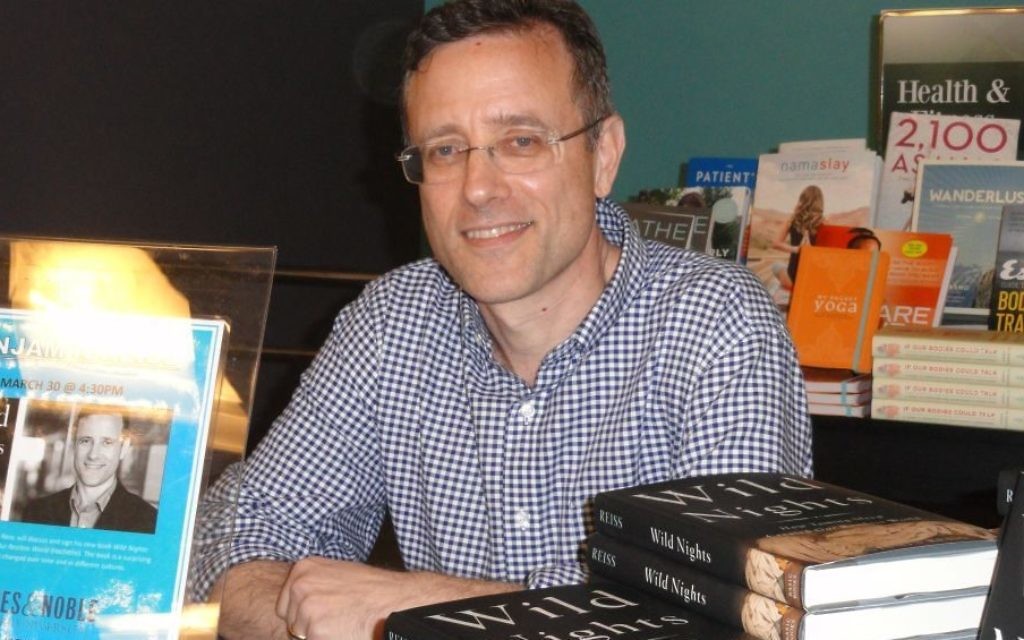

Emory professor and Bet Haverim member Benjamin Reiss explores the unnatural ways we try to force sleep.

We have been sleeping all wrong, and we are teaching our children bad sleeping habits, Emory University English professor Benjamin Reiss says in his new book, “Wild Nights: How Taming Sleep Created Our Restless World.”

Reiss, a Congregation Bet Haverim member, spoke March 30 during a book signing at the Barnes & Noble store on campus.

“My background is in cultural history,” Reiss said. “I teach in the English department, but I work in that vein, trying to see how ideas, assumptions and culturally learned behaviors change over time.”

Get The AJT Newsletter by email and never miss our top stories Free Sign Up

Sleep has changed tremendously the past 200 years, he said, “and those changes have created a lot of the mess we have inherited in our sleep world. How strange it is that this very basic biological activity every living creature needs to undertake in order to survive has become such a source of conflict and stress for so many people.”

The book grew out of a course Reiss taught alongside neurologist David Rye, a specialist in sleep science at Emory.

“I really learned a lot about the workings of sleep from a biological standpoint, and I brought to it readings on literature, philosophy, history and anthropology, trying to get at the social and cultural meanings of sleep, particularly as they evolved,” Reiss said.

“Before the 19th century it was unthinkable for families to spread out in ways we now expect them to,” he said. “The whole idea of a bedroom for a common home is a relatively recent invention. Most homes had rooms with overlapping functions for day and night. People slept in collective spaces, and in many societies it was common even for strangers to sleep together on certain occasions. It was only with the rise of industrialization that health concerns arose about large numbers of people packed together in factory boarding houses and so on that health authorities started aggressively trying to separate them. That played a big role pushing this idea of separate spaces.”

Increasingly, Europeans came to view co-sleeping societies as inferior, and we have inherited some of that stigma, Reiss said. “Children don’t want to sleep apart; we have to train them to do it. A lot of fuss and energy goes into it. The ritual of the bedtime story, to ease their passage into it, it becomes a zone of struggle in many families to get everyone on the right schedule and make sure they’re doing what they should.”

He laid out the “basic rules” for how Western society has decided to do sleep: “at night, more or less all at once for about seven to eight hours, in a private, specially appointed room that is sealed from the external world, noise-free, no distractions, probably climate-controlled, with a relatively soft surface that is somewhat customizable according to what your body likes.”

By Benjamin Reiss

Basic Books, 320 pages, $28

Reiss said it’s odd how we train our children to sleep according to strict guidelines and consult manuals and experts for advice. It doesn’t seem to stick because once you get children to learn to sleep appropriately, they grow up and have to adapt to new circumstances, and sleep becomes an ordeal.

The middle-class ideal is to put children alone, away from their parents and generally apart from siblings. “The main thing we should guard against is having them be too routinized because if they have to change their routine, like when a new sibling comes along, it can be very upsetting to them. If they are used to sleeping on a mattress that’s too comfortable, when they travel, they not be able to deal with the change.”

Which system is better, Reiss asks, the one in which the child thinks sleep is something to be rigidly adhered to or something that trains the child to be flexible?

The problem, Reiss said, is society’s obsessiveness with the subject. “We’ve created all this commercial interest around sleep. We have over 2,500 registered sleep clinics in this country. There’s a multibillion(-dollar) pharmaceutical industry related to sleep and waking. We have hundreds of products you can buy to monitor your sleep. So a lot of what we experience as disordered or disturbed sleep is a response to the expectations we bring to it.”

comments