American and Israeli Jews Don’t Understand Each Other

Differing views on Judaism and democracy are among the reasons why those from Israel and America don’t see eye-to-eye.

It’s hard to give up on a familiar worldview, even harder than giving up on comfort foods during our quarantine-driven isolation. With the world battling a murderous plague, with democracy under siege no matter, despite or because of the outcomes of the 2020 presidential election, some homemade chicken soup or spicy shakshuka can ease the pain and allow us to drift off into reveries of the way that things used to be. But only for so long.

Similarly, believing that every Jew still (if ever) axiomatically feels tied by faith, fashion, and ethnicity to the fate of every other Jew in this post-Holocaust world can be as comforting as that chicken soup or shakshuka. We can, for example, disregard the Haredi and ultra-Orthodox alliance that tried (unsuccessfully) to delegitimize Reform, Conservative and Reconstructionist Judaism during the recent virtual World Zionist Congress; we can pretend that the agonizing disagreements over Israel’s intended annexation of significant parts of the West Bank didn’t really happen. But we can quiet our nagging feelings of rejection, pain and even rage for only so long before reality dulls our taste buds, and the unpleasant truth sinks in. That shakshuka will grow cold, uneaten. We will have no comfort.

We cannot keep turning a deaf ear to the familiar words from “Porgy and Bess:” “it ain’t necessarily so.” Soup and shakshuka can serve to divert us from social injustice and the threat of armed militias only until the next Breaking News Alert. But they cannot make us continue to believe that all Jews see ourselves as responsible for one another because we share a common fate, when reality and bitter experience strongly suggest otherwise.

There are stark, profound differences between the Israeli Jewish community and the American Jewish community. We need to acknowledge those differences before we can even begin to deal with them. There are social, religious, economic, political, cultural and historical differences – and many more.

Political systems, for example, are shaped both by thought and experience. Inevitably, many Israelis view democracy differently than do American Jews, even as many American Jews view Judaism differently than do Israeli Jews. We use “Judaism” and “democracy” as if everyone understands them the same way. But they don’t. They never have.

And because they don’t, American Jews often have a difficult time understanding how Israelis can claim that theirs is a Jewish and democratic state. Israelis cannot understand why so many American Jews seem to privilege their commitment to democracy over their embrace of Judaism. Our default belief is that Israeli Jews and American Jews pretty much think the same way and carry the same set of priorities and concerns. But they don’t. And even when they do share some priorities and concerns, like the builders of the Tower of Babel they have acquired a profound inability to understand each other.

And that is why Rabbi John Rosove and I, together with a stellar group of social scientists and activists from both Israel and the United States, chose to create the book “Deepening the Dialogue: Jewish-Americans and Israelis Envisioning the Jewish-Democratic State,” recently published by CCAR Press. John and I are committed liberal Zionists; both of us have carried major responsibilities within the Reform movement, The Jewish Agency for Israel and the World Zionist Organization.

Our goal was simple: We wanted to forge a shared path along which Israeli Jews and American Jews could walk, coming to truly understand each other while actively working in full and equal partnership for social justice in Israel. There is only one document extant that embraces the full range of Israel’s foundational values and concerns: Megillat Ha-Atzmaut, Israel’s Declaration of Independence. We strove to bring Israeli social activists and American Jewish social activists together in what Rabbi Judith Schindler and Rabbi Noa Sattath have called “Social Justice Zionism.”

An Israeli activist and an American activist would together explore each of the values embedded in the Megillah. Gender equality. Economic justice. Full participation of Israel’s Arab citizens in Israel’s cultural and political life. Equal rights for the diverse forms of Jewish religious expression. And so much more. Every chapter in the book would be published in Hebrew and English, so that we could “hear” each other better.

By working together, our authors would come to understand each other. Side by side, they would craft sharp and loving critiques of Israel as a Jewish and democratic state – as viewed and understood from two differing positions. Together they would build a platform of understanding so that actual projects, actual social justice undertakings, could be launched in Israel. Comforting worldviews would be adjusted, language clarified, and bland assumptions set aside.

Recent surveys from across the spectrum make clear that Israelis feel attached to the Jewish people, but overwhelmingly they do not want non-citizens intervening in matters of Israeli defense and survival. Israelis are also cautious about welcoming diaspora involvement in domestic matters, such as the struggle for civil marriage, for broad conversion rights and for weakening the power of the Chief Rabbinate. And a majority of Israelis are worried about the long-term viability of the non-Orthodox American Jewish community.

There is a better way. “Deepening the Dialogue” cannot promise that the path will be smooth, but only that those who choose to walk it together will enrich the Jewish future.

And I still want that shakshuka.

I am very grateful to Rabbi Uri Regev, president of Hiddush – For Religious Freedom and Equality, for having shared with me a wide range of sophisticated studies regarding core values and attitudes embedded within contemporary Israeli society.

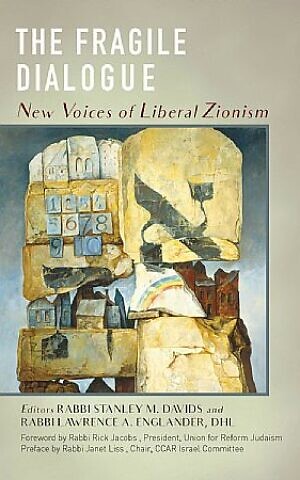

Rabbi Stanley M. Davids is rabbi emeritus of Temple Emanu-El. He has held leadership positions in the Association of Reform Zionists of America and Israel Bonds, among others. He is also the co-editor of “The Fragile Dialogue: New Voices in Liberal Zionism.”

comments