The Not-So Secret Jewish History of the Jelly Doughnut

How Jewish immigrants pioneered American doughnut culture.

Chana Shapiro is an educator, writer, editor and illustrator whose work has appeared in journals, newspapers and magazines. She is a regular contributor to the AJT.

What would Chanukah be without jelly doughnuts? Called sufganiyot in Hebrew, this confection is a Chanukah treat throughout the Jewish world. Deep-fried jelly doughnuts recall the oil that burned miraculously for eight days in the second-century BCE Temple in Jerusalem. The word sufgania comes from sfog, meaning “sponge,” which refers to the process by which the oil soaks into the dough.

According to Israeli writer Carol Green Ungar, the earliest reference to fried Chanukah pastry is found in the writings of Rabbi Maimon ben Yosef, the father of Rabbi Moses Maimonides, who lived during the 12th century. “One must not make light of the custom of eating sofganim [fried fritters] on Chanukah,” he wrote. “It is a custom of the Kadmonim [the ancient ones].” The fritters he mentions were likely a sweet, syrup-coated pancake.

Today’s plump, jelly-filled doughnut is a modern Western innovation. Gil Marks, in his “Encyclopedia of Jewish Food,” dates the first modern sufganiya to 1485, when a recipe for gefullte krapfen (filled doughnuts) appeared in “Kuckenmeisterei (Mastery in the Kitchen),” possibly the first published cookbook, printed on Gutenberg’s original printing press.

The popular Christmas treat was made from two rounds of yeast bread, with jam between them, fried in lard. Jews substituted kosher chicken or goose fat and served their own version on Chanukah. Eventually, the fleishig doughnut traveled to Poland, where it was renamed ponchik. Marks writes that the first filled-and-fried pastries in Europe contained savory fillings such as meat or mushrooms. Fruits imported in the 16th century from European colonies in the Caribbean enabled bakers to use fruit preserves as fillings, and Polish Jewish immigrants to Palestine in the early 20th century served fruit-filled doughnuts on Chanukah.

Food historian Emelyn Rude describes sfeni, small, deep-fried balls of yeast dough that were eaten on Chanukah by Jews in North Africa and brought to Europe by Jewish merchants. These doughnuts were usually drenched in sugar syrup. Today, many Sephardim prepare Chanukah bimuelos, fried yeast doughnuts steeped in a sugar syrup, and often flavored with lemon, rose or orange-blossom water. Egyptian Jews call these sticky sweets zalabia; Iraqi Jews call them zengoula.

Marks explains that sufganiyot became Chanukah’s culinary symbol in Israel because of the Histradut, Israel’s national labor federation. Founded in 1920 during the British Mandate of Palestine, the Histadrut organized economic opportunities for Jewish workers, and in the late 1920s, promoted manufacturing jelly doughnuts to create jobs. Anyone with a grater and frying pan could make latkes at home, but sufganiyot preparation was very labor-intensive. The dough had to be kneaded, rolled and cut by hand, then fried in small batches on a kerosene heater known as a primus. The manufacture of sufganiyot for Chanukah created jobs for trained Jewish workers.

The Histadrut’s plan succeeded. According to a 2018 Chabad report, nearly 20 million Israeli sufganiyot are consumed around Chanukah — about three doughnuts per citizen. A recent Jewish Action story claimed that more Israelis eat sufganiyot than fast on Yom Kippur.

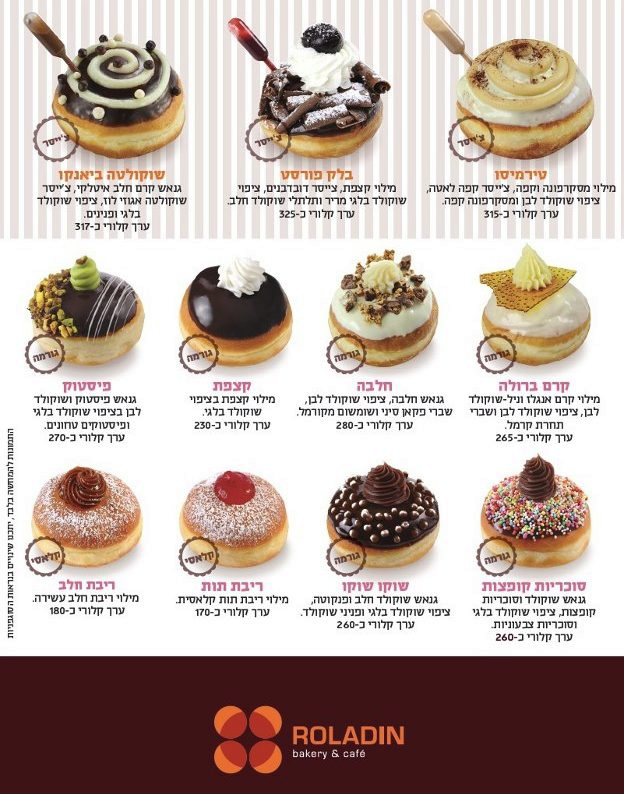

Israeli news sources confirm that the Israeli Defense Forces purchase more than 50,000 sufganiyot for its troops on each day of Chanukah. In addition to strawberry filling, bakeries now include cappuccino, Bavarian cream, cheesecake, Bamba, and even alcohol. In the 1980s, Argentinian Jewish immigrants introduced caramel filling. For health-conscious Israelis, “minis” are half the size of the traditional 3.5-ounce jelly doughnut.

Rude mentions that Jewish doughnut businesses flourished following the coffee craze that swept through Europe. The first European coffeehouses, established in the city of Livorno in 1632, were owned by Jews. The first English coffeehouse was opened in Oxford in 1650 by a Jewish immigrant from Lebanon named “Jacob the Jew.” Jews owned cafes in France, Germany, and the Netherlands, and as coffee grew in popularity, so did doughnuts.

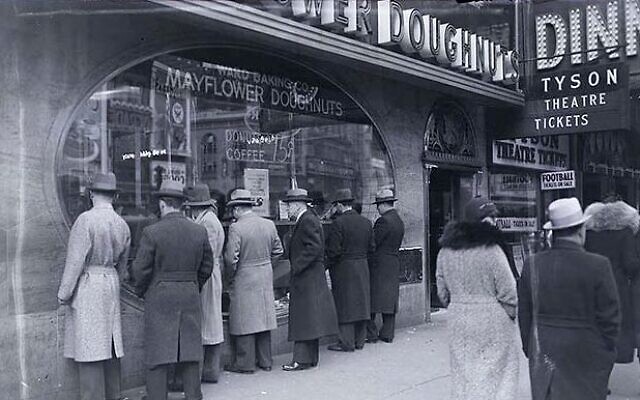

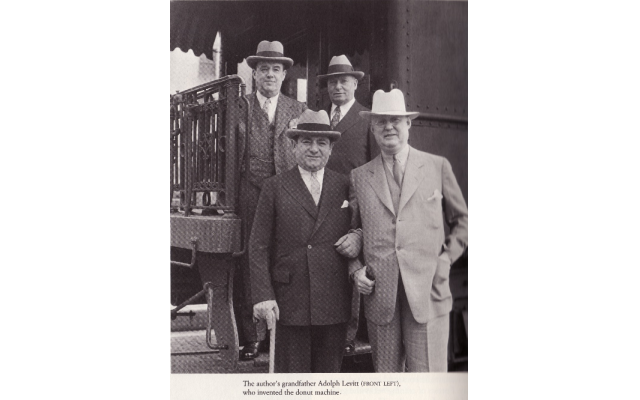

Jewish immigrants also strongly influenced American doughnut culture. Jewish refugee Adolph Levitt invented the first automated doughnut machine in 1920, the “Wonderful Almost Human Automatic Donut Machine,” which speedily produced uniform doughnuts. Doughnuts were the featured food at the Chicago World’s Fair in 1934, hyped as a symbol of American mechanization. In 1925, Levitt manufactured a doughnut mix for bakers to use with his machines, guaranteeing consistent quality. By the 1950s, Levitt’s Doughnut Corporation of America was selling over $25-million-worth of doughnut-making equipment annually, and doughnuts became America’s favorite pastry. When Levitt opened a doughnut establishment in Times Square, people stopped to watch his new invention, often blocking traffic.

William Rosenberg, of Dorchester, Mass., launched the largest doughnut shop chain in the world, Dunkin’ Donuts. Nearly half of his catering business, delivered in food trucks whose sides opened up to display food on stainless steel shelves, consisted of coffee and doughnuts; consequently, he opened a doughnut shop with 52 varieties, where customers could sample a new flavor each week of the year. In 1950, Rosenberg changed the name of his chain from the original Open Kettle to Dunkin’ Donuts, and in 1955, franchised the business to other stores. By the time of Rosenberg’s death in 2002, there were more than 12,000 Dunkin’ Donuts locations in nearly 45 countries, including 40 outlets under kosher supervision.

What about Krispy Kreme? According to the brand’s website, “Our plant in Winston-Salem, N.C., where the mix is made is certified Kosher. In addition, some of our stores, [including Atlanta] … have been certified Kosher.” The North Carolina Museum of History’s website credits baker Vernon Rudolph, who worked at his uncle’s doughnut shop and used a yeast-dough recipe, with the company’s origins. In 1937, Rudolph rented a building in Winston-Salem and made doughnuts for local grocery stores, gaining fans by cutting a hole in the wall of his store and installing a window. In the 1940s, Rudolph opened his own mix plant and manufactured doughnut-making equipment, eventually offering franchises and creating the Krispy Kreme Corporation in 1947.

A 2019 story reported by CNN Business offered an ironic twist on the sale of Krispy Kreme to the JAB Holding Company. The billionaire Reimann family of Germany, which owns a controlling stake in JAB, admitted that their Nazi forebears were major supporters of the Third Reich as early as 1931, used slave labor and were responsible for sexual abuse in their factories and villas during World War II. The family announced that they would donate $11.3 million to charity to atone for their Nazi past.

Today, Chanukah celebrations around the world feature both manufactured and homemade jelly doughnuts — delicious tributes to Jewish ingenuity and the single cruse of oil that lasted eight days.

- Holiday Flavors

- Community

- Chana Shapiro

- Mayflower Doughnut shop

- Times Square

- sweet treats

- Israel

- William Rosenberg

- Dunkin’ Donuts

- Jewish immigrants

- refugee

- Adolph Levitt

- sufganiyot

- Chanukah

- Donuts

- jelly doughnuts

- Krispy Kreme

- BCE Temple

- Jerusalem

- Carol Green Ungar

- Rabbi Maimon ben Yosef

- Rabbi Moses Maimonides

- Kadmonim

- Fritters

- Gil Marks

- Encyclopedia of Jewish Food

- Kuckenmeisterei (Mastery in the Kitchen)

- Poland

- Caribbean

- Polish Jewish immigrants

- Palestine

- North Africa

- europe

- Emelyn Rude

- Histradut

- Yom Kippur

- Israeli Defense Forces

- strawberry filling

- Bakery

- cappuccino

- Bavarian cream

- Cheesecake

- Bamba

- Alcohol

- European Coffe Houses

- Livorno

- Oxford

- france

- Germany

- Netherlands

- Chicago World’s Fair

- Doughnut Corporation of America

- Winston-Salem

- Atlanta

- North Carolina Museum of History

- Vernon Rudolph

- CNN Business

- JAB Holding Company

- World War II

- Reimann family

comments