Was Elvis, ‘King of Rock and Roll’, Jewish?

The NBC Comeback Special created by Bob Finkel, Steve Binder and Billy Goldenberg revitalized Elvis Presley’s career.

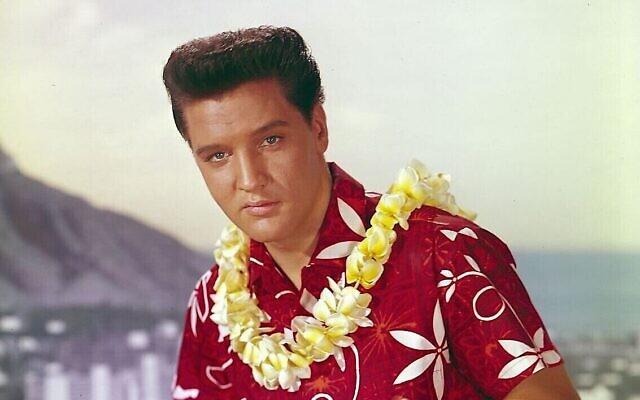

When director Baz Luhrmann’s new film, “Elvis,” finally hits the nation’s screens next June, it will mark yet another comeback for the King of Rock and Roll. Starring Tom Hanks as Elvis’s manager, Colonel Tom Parker, and Austin Butler as the legendary singer, the biopic comes 53 years after another comeback, the NBC television special also simply titled, “Elvis.”

The television program, which was first broadcast on Dec. 3, 1968, was thought to be just another holiday special meant to sell Singer sewing machines for the program’s sole sponsor.

But in the hands of the three key members of the show’s creative team, the program became an ambitious attempt to revive the reputation of The King.

For the executive producer, Bob Finkel, director Steve Binder, and music composer and arranger Billy Goldenberg — all of whom were Jewish — creating what came to be called “The Comeback Special” was nothing less than a media resurrection intended to bring the moribund King back to life.

During much of the 1960s, Presley had shunned live performances. He largely devoted himself to a long string of forgettable films with often uninspired soundtracks that produced a quick buck for him and his manager but did little to further his career.

By the time he had finished the 31 films he had turned out during the 1960s, many of his fans had deserted him for rock and roll groups that had been inspired by the Beatles and Rolling Stones. He hadn’t had a number one single on the charts for six years.

In his initial meeting with Binder, the director frankly told the singer that his career was “in the toilet” and that doing another holiday program like the one his manager was suggesting might be fine for Perry Como or Andy Williams but would do nothing for him.

In an account of how “The Comeback Special” came to be, published by a small, privately owned publisher in 2010, Binder described how he took Presley out to Hollywood’s Sunset Boulevard. As they stood there, to Presley’s astonishment, nothing happened. Cars whizzed by, and a few pedestrians walked past without a word. Binder had made his point to a performer who had largely lost touch with his audience.

From then on, the iconic performer, who had come out of nowhere in the mid-1950s and seemingly transformed popular music overnight, put himself in the hands of his new Jewish collaborators.

It wasn’t the first time Presley had grown close to Jews. As a teenager, his family had lived in Memphis, on the ground floor of a small apartment building. Upstairs, Rabbi Albert Fruchter and his family also lived in a small apartment.

The young rabbi and his wife had come to the mid-South community to establish the city’s first Jewish day school. The young Presley became the family’s “Shabbos goy,” turning on the lights and the stove for the observant family on Friday nights and Saturdays.

Down on Beale Street, the Memphis entertainment mecca, he became a lifelong customer of the Lansky Brothers. Their menswear shop was also a favorite of the African American entertainers who appeared in Beale Street’s bars and clubs. Three of his high school friends, the so-called Memphis Mafia — George Klein, Marty Lacker and Alan Fortas, a nephew of the Jewish Supreme Court Justice, Abe Fortas — were Jewish.

But what none of these early friends knew was that Presley himself was, at least, technically also Jewish. His maternal great-great grandmother was a Lithuanian Jew named Nancy Burdine, who died in 1887. One of her direct descendants was Elvis’s mother, Gladys Love Smith, who married Vernon Presley in 1935. They named their son Elvis Aron, after Moses’s brother, Aaron, the first high priest of the Israelites. El, as he was called by many who later knew him, was also one of the names of G-d in the Jewish scriptures.

When Presley was a youngster, his mother confided to him the family secret, but admonished him to keep it to himself. In Tupelo, Miss., where Elvis was born, there was a deep undercurrent of anti-Semitism at the time. Congressman John Rankin, who represented the town for 30 years — including the years when Presley was growing up — had a well-known hatred for Jews.

Today, though, in the small museum that adjoins his birthplace in Mississippi, there’s a Chanukah menorah that Presley was said to have admired as a child.

When his mother died in 1958, Elvis marked her grave with a granite tombstone that included a Star of David. Later in life he wore the star in gold around his neck, as well as a golden chai, the Jewish word for life.

Today, the headstone marks Gladys Love Presley’s grave in the Memorial Garden at Graceland, the Presley shrine and his Memphis home. The golden chai is housed in one of the building’s display cases. All of it will be viewed by the thousands who assemble, reverentially, in January, for what would have been the King’s 87th birthday.

But as he was being guided through the preparations for his holiday special, which was actually recorded in the summer of 1968, his thoughts were less on the past than on his future.

Finkel, Binder and Goldenberg, in an effort to give Presley a new image for their show, had dressed the singer in a tight-fitting black leather suit with a black leather wrist cuff. For four hours they recorded a largely impromptu jam session in a casual setting with several of his favorite musicians. As the cameras rolled, Presley largely ad-libbed his way through more than 13 years of hit songs released since he first teamed up with the Colonel.

What the audience, largely made up of adoring young women who surrounded the stage, saw was a musician at the height of his powers — relaxed, charming and in control. The one-hour special was seemingly magical, both in the way it transformed the performer who had almost forgotten how to perform before a live audience and the new image it gave him after years of ups and downs. It was, in the words of Binder, like watching a black panther in his cage.

For the finale, the Colonel had told Binder to come up with a traditional Christmas song and then end the broadcast with a short holiday farewell. But Binder and Presley had other ideas.

Robert had been assassinated in Elvis’s hometown in April, just a few months prior. Early in June, as the show was being prepared for the cameras, Robert Kennedy was shot and killed in Los Angeles. The occasion demanded something special.

In the last few minutes of the broadcast, Presley stepped onto a stage with just the oversized letters of his first name spelled out in red behind him. Overnight, Billy Goldenberg and Earl Brown, who was an African American working on the program, had come up with one of the most powerful songs Presley would ever record, “If I Can Dream.” In an impassioned performance, Presley made a plea for understanding and reconciliation.

If I can dream of a better land

Where my brothers walk hand in hand

Tell me why, oh, why, oh why can’t my dream come true…

We’re lost in a cloud with too much rain

We’re trapped in a world that’s trouble and pain

But as long as man has the strength to dream

He can redeem his soul and fly.

At the age of 33, this entertainer, who had once been cautioned to keep his Jewish roots a secret, had finally come home. In 1968, just ten days prior to Chanukah, and 13 years after he and the Colonel had first cemented their relationship, Elvis Presley delivered a bar mitzvah speech worthy of any synagogue in America.

- Chanukah

- Community

- Bob Bahr

- Elvis Presley

- Memphis

- 1968 Comeback Special

- Tupelo Mississippi

- Graceland

- Moses

- Aaron

- NBC

- Singer sewing machines

- Hollywood’s Sunset Boulevard

- Menorah

- Chai

- Star of David

- Beale Street

- Lansky Brothers

- Colonel Tom Parker

- Baz Luhrmann

- Gladys Love Presley

- Nancy Burdine

- Rabbi Albert Fruchter

- Vernon Presley

- Tom Hanks

- Billy Goldenberg

- Bob Finkel

- Steve Binder

- Perry Como

- Andy Williams

- John Rankin

- George Klein

- Marty Lacker

- Alan Fortas

- Supreme Court Justice

- The King

- Anti-Semitism

- Abe Fortas

- King of Rock and Roll

- Reverend Martin Luther King Jr.

- Robert Kennedy

- Beatles

- Rolling Stones

- Earl Brown

- If I Can Dream

- bar mitzvah speech

comments