Atlanta Families’ Holocaust Artifacts Documentary

AIB-TV presents video to counter Holocaust denial and anti-Semitism.

“Preserving Holocaust Artifacts,” the latest Atlanta Interfaith Broadcasters TV documentary, aims to counter Holocaust denial and anti-Semitism. The timing couldn’t have been better. The 26-minute video premiered just after Yom Kippur and only days after the latest anti-Semitic graffiti incidents occurred in various Cobb County schools. Subsequent screenings continue through Oct. 19. It’s also available on Facebook.

Months in the making, the documentary focuses on a couple of Atlanta families who discovered troves of letters, photographs and documents their families had saved for more than 75 years. Both families are donating their collections to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C.

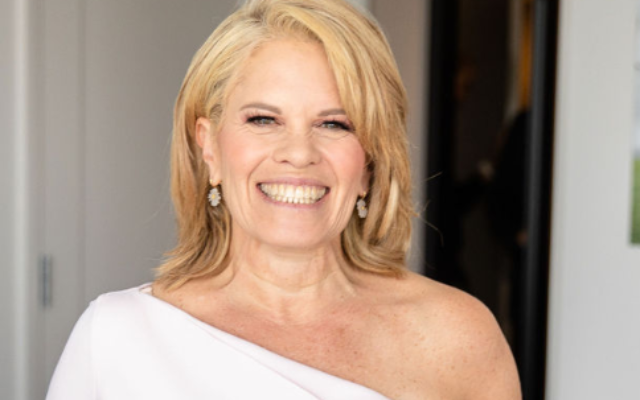

“We had intended to air the piece earlier,” acknowledged Audrey Galex, AIB’s community engagement manager and producer of the documentary. Galex, who also narrates the documentary, said the stories related by Alli Allen and Naomi Liebman really touched her. “I think about my own childhood, carpooling with kids whose parents were survivors,” Galex told the AJT.

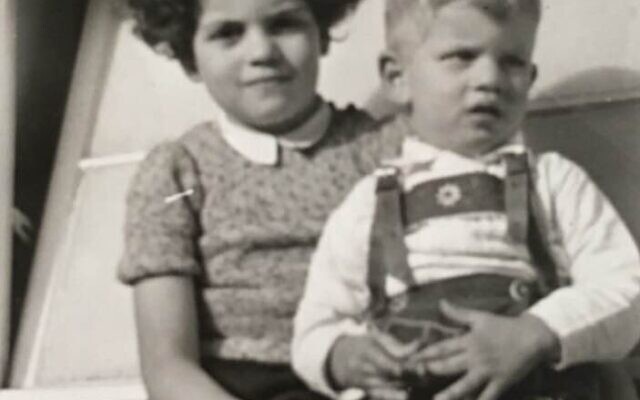

In the film, which is part of a series for “AIB Presents,” Atlantan Alli Allen said she knew of her family’s Holocaust history growing up, but it wasn’t until after her grandmother, Paula Hartstein Marx, died in 1999 and her mother, Inge Marx Robbins, found boxes of letters and artifacts in her attic, that the story became clearer. Her maternal grandmother, Allen said, never spoke about the fact that her parents and sister died in the Holocaust. But the letters, written almost once a week between 1938 and 1941 on onion-skin paper in German, related how progressively desperate they were to flee Europe.

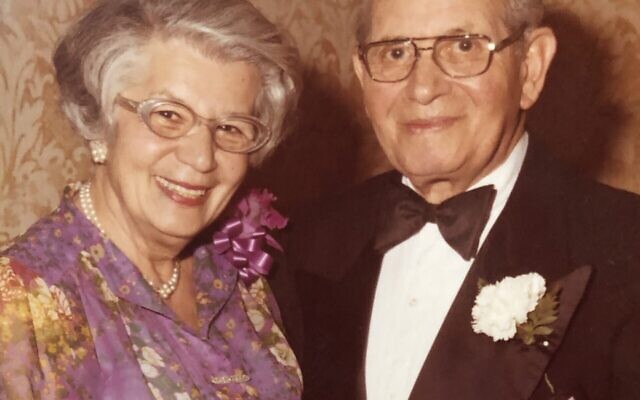

“The letters started within a week of my grandparents leaving,” said Allen, which by chance was in November 1938 — a week before Kristallnacht. “They wrote, ‘I can’t believe you left.’” Then her great-grandparents Blanka and Max Hartstein in Stuttgart and her great aunt in Prague started preparing for their hoped-for journey to America. “They were writing about their efforts to get visas and passage out of Europe. They took English lessons, and my great aunt was learning how to sew” so that she would have employment when she arrived in the U.S.

In addition to letters and photographs, the family stuck in Germany sent clothes that they thought would be useful upon their arrival in America. But suddenly the letters stopped. In 1942, the family received a last postcard from the Theresienstadt concentration camp via the Red Cross. Allen learned later that her great-grandparents were at the camp for two years, while her grandmother’s sister was there for six months. “We have their death dates,” she said. “The letters are hard to read because you hope for a good outcome, even when you know there isn’t one,” she added.

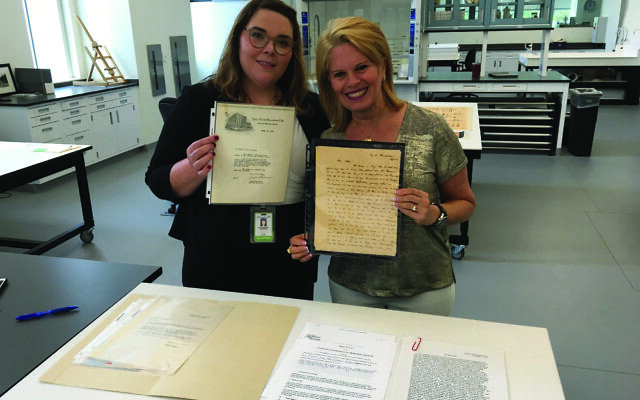

The documents became a family project, Allen relates. Her mother, now 92, and uncle “worked on getting the letters translated, organized all the business correspondence from my grandfather, and assembled the bound volumes of all the translated letters. My cousin, Renae Marx Popkin, helped assemble and print the books.” The family then reached out to the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum. “We met with a curator and signed the documents to turn over the collection to the museum,” said Allen.

As Robert Tanen, director of the Museum’s Southeast Regional Office, recalled, “Alli Allen was in the process of donating one of the largest family collections that the Museum has acquired from Atlanta when the pandemic struck.” The translated letters are already at the museum, but Allen still has the originals.

Pre-pandemic, the museum would receive one or two collections from families every day, said Kyra Schuster, curator at the National Institute for Holocaust Documentation at the U.S. Holocaust Museum. When the pandemic struck in early 2020, the museum closed, and employees only worked virtually. Schuster said she’s now coming into the office a couple of times a week and that they are “starting to make arrangements for receiving collections” from many different families.

The collections range from a button to “an entire storage unit,” said Schuster. The Allen family collection includes letters that her grandfather sent to Germany after the war as he attempted to claim restitution. Her grandfather was born in Buttenhausen and was able to get his mother and nephew out of Germany.

In May, the U.S. Holocaust Museum worked with Atlanta’s Breman Museum to present a two-part virtual series that helped to explain the Museum’s process for reviewing and acquiring Holocaust artifacts. According to Leslie Gordon, the Breman’s executive director, “Our collections policy is limited to Georgia and Alabama, and we encourage donors to donate to either or both. Also, the U.S. Holocaust Museum has a loan policy, so that if we wanted to focus on something they had collected, we could borrow it easily. We work together because what we do is so important.”

Schuster suggested that anyone who has Holocaust-related artifacts can contact the U.S. Holocaust Museum either by email (curator@ushmm.org) or through a form on its website (www.collections.ushmm.org). “People used to walk in the door” with documents pre-pandemic, she said.

Prospective donors should provide a description of the artifacts, she added. “We want to make sure we’re the right repository for the items,” said Schuster. “Sometimes we refer people to other institutions. Once we determine we want to acquire the artifacts, we make arrangements for the shipping.” The museum will then preserve and digitize the documents so that they can be accessed by researchers or the public.

Only about one percent of the museum’s collection is on display at any given time. The rest is kept in a special facility in Maryland under strict preservation conditions. Schuster said that she thought donations would “peak in the 1990s, but we’re busier now than ever. I think we’ll be just as busy in 10 years.”

- Then & Now

- Local

- Jan Jaben-Eilon

- U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum

- Breman Museum

- AIB-TV

- Video

- Holocaust Denial

- Anti-Semitism

- Blanka and Max Hartstein

- holocaust

- Alli Allen

- Kyra Schuster

- Inge Marx Robbins

- Albert Marx

- Paula Hartstein Marx

- Hugh Marx

- Atlanta Interfaith Broadcasters TV

- Yom Kippur

- Cobb County Schools

- Atlanta

- Washington D.C.

- documentary

- Letters

- photographs

- documents

- Clothes

- Audrey Galex

- Naomi Liebman

- German

- europe

- Kristallnacht

- Stuttgart

- Prague

- Germany

- America

- Red Cross

- Family Project

- Renae Marx Popkin

- Robert Tanen

- pandemic

- National Institute for Holocaust Documentation

- Buttenhausen

- Leslie Gordon

- Holocaust artifacts

comments