Atlanta Medical Duo Assists in Ukraine

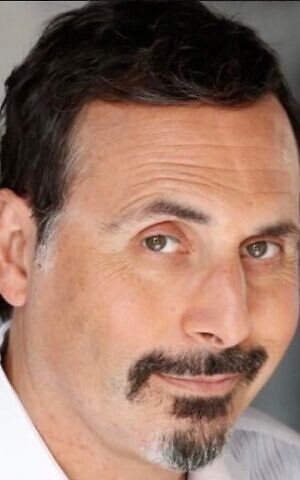

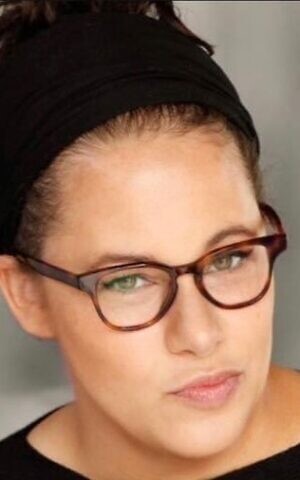

Adrienne Clark Usadi and Moshe Usadi went to Ukraine to work in the field in Dnipro.

Chana Shapiro is an educator, writer, editor and illustrator whose work has appeared in journals, newspapers and magazines. She is a regular contributor to the AJT.

On rare occasions, something happens in which a person can make a real difference in the world. Just such an event, in March 2022, prompted Adrienne B. Clark Usadi and Moshe Usadi to spend two weeks away from their children and their medical practice, Qualified Quacks Concierge Medicine.

Adrienne, a nurse who spent many years in hospitals in baby-delivery, labor, pain management, and assisting with procedures in hospital plastic surgery, and Moshe, whose background included being a family practice physician and practicing emergency medicine, took the opportunity to bring their knowledge and training to Ukraine.

They decided to go to Ukraine shortly after they saw reports about the bombing of the maternity hospital in Mariupol. They learned that Russia was targeting non-combatants (civilians), health centers and scores of other hospitals, and Adrienne reports, “I couldn’t just stand by and watch, and my husband felt the same.”

They brushed up on emergency procedures (Moshe was already well-experienced in this area; Adrienne’s experience was more limited), with the goal of becoming, in Adrienne’s words, a “well-oiled team” with mastery of “in the field” procedures.

They had to anticipate which medications and supplies would be needed and have back-up plans if the preferred items were unavailable.

The Usadis were not sponsored by any agency, and it would take months before they could be reviewed by non-government groups, so they got resourceful. They had been the medical team for March of the Living South, and they contacted the director, Jack Rosenbaum, who they expected had contacts in Poland and Ukraine.

They also joined Facebook groups dedicated to aiding Ukraine. Between these two resources, they received points of contact in Poland and Ukraine and learned that the best place to fly into the area was Krakow, Poland. They booked a flight through a company that exclusively discounts airfare for medical mission trips.

They were allowed only six bags of medicine and medical supplies, which they filled from their own practice, contributions from colleagues, and a large amount from Northside Hospital. Their nearly $8,000 worth of supplies were donated to the Ukraine Hospitallers; however, the Usadis kept minimal supplies with them in case of personal injuries.

Their staging location was Dnipro. From Krakow, train travel would take too long to Lviv, where they would meet their driver, Chris, who would take them to their destination, and they decided to go to Lviv by Uber. While the border crossing from Poland was smooth, their crossing into Ukraine entailed being questioned about where they were going and having their luggage searched; however, showing their medical ID badges and being loaded with medical supplies helped to streamline the process.

On route, they were pulled off to the side of the road behind many other vehicles. Subsequently, they found out that everyone was held in place because an alarm had been sounded. Once the “all clear” was given and their crossing documents were processed, they proceeded to Lviv with their driver, Chris.

In Lviv, the Usadis purchased a sim card and burner phone (a cheap phone with minimal features that can be easily discarded and untraced) because the Russians were targeting phones that showed USA or European origins. Lviv was a beautiful, charming city, although soldiers were present, indicating it was a military town.

There were also places helping long lines of refugees. The Usadis’ supplies were added to those in Chris’s truck, filling it top to bottom.

The drive from Lviv to Kyiv took 12 hours, mainly due to fuel issues and checkpoints. Gas was rationed (4.5 gallons a time) unless one had an army permit, and there could be a one-to-two hour wait. Chris stopped wherever he could, trying to keep a full tank and full extra containers he carried in his truck.

On the drive between Lviv and Kyiv there were increasing defensive positions, including high walls of sandbags and shacks that were lookout and fighting positions. Tires were stacked in the middle of major roads, forcing drivers to slow, and many had checkpoints. Roads became heavily pockmarked as they got closer to Kyiv, and there were curfews in major cities. At one point, they had a flat tire from a huge pothole caused by the war, and the setback meant they would not reach Kyiv before the 10 pm curfew.

To avoid using valuable gas to maintain heat, they would have to endure a freezing night in the truck. Fortunately, a trucker and his wife saw them and took them to a hostel just outside the city limits. The next day, they drove another 12 hours to Dnipro.

Their home base was a hotel/apartment in Dnipro, where the accommodations were better than the Usadis expected, and, after acclimating to the war environment, they were embedded with a medical team. They used their skills in unexpected ways, such as turning box trucks into makeshift patient transports. It was common for both patients and refugees to be transported at the same time from areas of active fighting, and ambulances and transport vehicles were often destroyed near the front line, thus there was a constant need to replace them.

Air raid sirens were frequent in Dnipro, but somehow life carried on, and residents didn’t scramble for shelter whenever they sounded. When questioned about this, their interpreter, Roman, reflecting the Ukrainians’ humor under pressure, joked about the Russians’ “bad aim.” Curfew in the city required being within the checkpoint, turning off all lights and pulling the blinds, so as not to make an easy target for bombing.

Adrienne sums up their two weeks, “We learned a lot, and there are many significant moments that impacted us. One was the resilience of the Ukrainian people…[whose] mindset was basically, ‘This is our country, we are here to stay, and we will do what it takes to protect our country.’ In the beginning of the war, Dnipro came under serious bombing (about a month before we arrived). The Menorah Center, [not far from the Usadis’ lodging], became a place of refuge, and the community helped people evacuate, feed refugees, and provide shelter.

“Our last days in Ukraine fell over Shabbat. We went to services at the shul attached to the Menorah Center, and it was wonderful to see Judaism thriving despite the war. Rabbi Kaminezki invited us to lunch in one of the ballrooms of the center, a three-course affair for over 100 people. There was a beautiful mix of Jews and non-Jews who were staying at the center, helping Ukraine. I cannot begin to describe the immense feeling that overtook me as I sat among this lovely community, and my gratitude to Hashem for sparing this community from the destruction and devastation other parts of Ukraine have endured.”

After their Ukraine experience, the Usadis became certified in TECC (tactical emergency casualty care) in Israel, knowing that trauma conditions away from a hospital are very different from what doctors typically experience. For trauma in the field of battle, a doctor learns temporary “fixes” with basic supplies to help until the patient arrives at a health care facility. One learns that training in the field is essential, and important basic supplies include everyday zip-lock bags and plastic wrap.

- News

- Community

- Chana Shapiro

- Adrienne Clark Usani

- Moshe Usani

- Ukraine

- russia

- March of the Living

- Jack Rosenbaum

- northside hospital

- checkpoint

- burner phone

- sim card

- ID badge

- soldiers

- Mariupol

- Dnipro

- Kyiv

- Lviv

- Krakow

- Poland

- Menorah Center

- resilience

- curfew

- Bombing

- Medicine

- civilians

- health center

- nurse

- Doctor

- emergency medicine

- physician

- pain management

- sirens

- sandbags

- Rabbi Kaminezki

- ambulance

- Qualified Quacks

- Ukraine Hospitallers

comments