Directors’ Cut

A few of the AJFF’s most heralded directors spoke to the AJT this week about the process of making a film and the importance of film festivals.

A few of the AJFF’s most heralded directors spoke to the AJT this week about the process of making a film and the importance of film festivals. These four directors demonstrate how diverse the AJFF’s offerings really are, from documentaries to comedies and everything in between.

While some may think a director simply sits in a tall chair yelling “Action” and “Cut,” these storytellers let us see behind the curtain and into the minds of rising stars in the world of Jewish filmmaking.

Jamie Elman and Eli Batalion on ‘Chewdaism’

Making their way around the world through food is not new to Jamie Elman and Eli Batalion, but their film, “Chewdaism: A Taste of Jewish Montreal,” takes them on a novel journey — home.

Though the pair first met in high school, their partnership really blossomed when they started their YouTube series, “YidLife Crisis.”

“It was 2005 in Los Angeles and we got to know each other through a mutual friend and realized we had a lot of similarities in our comedic leanings,” Batalion said.

The series – and its spinoff docuseries, “Global Shtetl,” – has taken them across the world, visiting places with deeply ingrained Jewish roots like Tel Aviv and Krakow. But the pair felt the need to do something special for Montreal.

“We decided we would turn the cameras back on our own hometown, and we had to do it in the most deluxe way,” Batalion said. Food as a vehicle simply seemed like the most natural fit to tell the stories the pair wanted to tell.

“Any chance we can get to – professionally – stuff our faces with Montreal bagels and smoked meat is enough reason for us,” Elman said. “We’ve used food throughout the YidLife series as a way of talking about Jewish culture generally and in Montreal.”

The film is broken down into six meals, telling the history of Jewish Montreal, which, according to Elman, is really the story of Montreal more generally.

“Over the last 100 years, the Jewish community has had a huge impact on the city,” he said.

Batalion explained that “Chewdaism,” much like their Yidlife series, taught them a number of lessons about their hometown. In particular, the pair cited one of the meals from the film as especially informative.

“We go and have a dinner amongst Sephardic Jews,” he explained. “There’s a term being used a lot these days – Ashke-normative – and we tend to look at our history through that, we don’t think about those who arrived from elsewhere.”

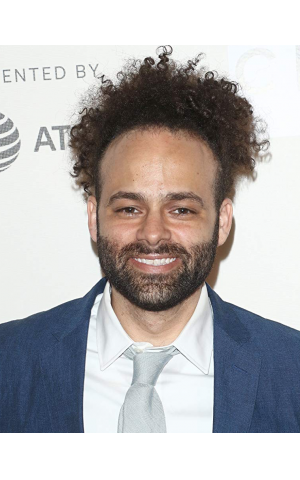

Shawn Snyder on ‘To Dust’

Dark, sometimes morbid humor is certainly a Jewish staple. That Jewish tone defines the background of Shawn Snyder’s film, “To Dust.” He knew from an early age that he wanted to be a musician or filmmaker, and his directorial debut is born out of his own emotional story, following the death of his mother.

“For some reason, right when my mom died, there was an epiphany-like shift that it was time to do film now,” he said. “The emotions that I was grappling with after her death lent themselves to film more than rhyming couplets in folk songs.”

He explained that he was fascinated by Jewish mourning customs.

“I’ve always felt that the Jewish mourning rituals and understanding of grief are so profound, even so ancient. This idea of focusing on the living rather than on death really resonated,” he said.

“To Dust” draws from some of Snyder’s own thoughts in the wake of his mother’s death and how those ideas could be taken to an extreme.

“There was this question of what’s happening with her body and it’s a question we all have and don’t engage with because our cultures and our societies make us hide those thoughts,” Snyder said. “I never went crazy with those ideas, but I saw how someone could.”

He described the process of putting the film together following a $100,000 grant from the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation, which — in addition to its scientific research — also supports art with a scientific theme. From there, his idea continued to resonate, and while he had originally planned to work with what he had and make a film, support kept flowing.

“Every step of the way I’m pinching myself, but here we are: ‘Let’s do the work.’ To this day I joke that Dayenu — that if we took $100,000 and went into the woods — it would’ve been enough,” he said.

Snyder explains that while he still wonders what it was that caused such widespread interest in the film, he believes it captures something special.

“We were tackling something so odd and so specific that could be so universal. We knew that we were walking a tonal tightrope and that everyone was taking this leap of faith with us,” he said.

Peter Kenneth Jones on ‘Henri Dauman: Looking Up’

One of the most heralded documentaries of this year’s AJFF would never have been put to film if it weren’t for Henri Dauman’s granddaughter and producer of “Henri Dauman: Looking Up,” Nicole Suarez.

Director Peter Kenneth Jones explained that while dating Suarez, he traveled to Paris to see Dauman’s first exhibition and was blown away by the photography on display.

“It was the first time I’d experienced his photography, and to a certain degree, the first time Nicole had experienced his photography as well,” he said. “During that time in Paris, she turned to me and said, ‘We have to make a movie about him.’”

He had never even met Dauman before, but Jones was already looking for a project to make his directorial debut, as he had served as an assistant to Jonathan Liebesman and Dean Israelite.

One running gag in the film is Dauman’s perfectionism, even throughout the filmmaking process as he directs Jones around and makes comments about lighting and shot framing.

“We knew going into the project that it was going to happen, and that it was something that we just can’t fight,” Jones said. “We decided we should have some way to include it, so we decided to always have cameras running to catch him doing what he naturally does. It definitely informed certain scenes; he literally adjusts the frame for one of our interview set-ups.”

And while the film likely would never have been made without Suarez’s insistence, in retrospect, Dauman looks back with gratitude.

“In a way, I’m glad I finally accepted,” he said. “With all the hatred going on around the world and rising anti-Semitism, I think that this will leave a witness to what happened in the World War and what it entailed. … There are fewer and fewer survivors of World War II and so the film can testify to the tragedies of war and why we should avoid it.”

Isaac Cherem on ‘Leona’

Born in Mexico City in 1992, Isaac Cherem, director of “Leona,” grew up within the tight-knit Mexican Jewish community. “The Jewish community in Mexico is very unique in its shape, its people and its ways,” he said.

Cherem’s interest in filmmaking was born of his love for music, which still heavily influences his filmmaking today.

In high school, a theater teacher approached him with an idea. “He wasn’t really asking me. He was like, you have to act in my play,” Cherem said.

Cherem enjoyed the energy of the theater and even won prizes at theater festivals. But his passion for film developed when his mother took him to a film festival because of his appreciation for films from different cultures.

“I met some people that invited me to participate in shoots and short films,” Cherem said. “And I met my partner, the producer of ‘Leona.’”

Cherem graduated from the Los Angeles Film School in 2011 and dreamt of making his own movie until the idea for ‘Leona’ popped into his head.

Calling the film his portrait of the Jewish community in Mexico, Cherem highlights the flaws and the beauty of growing up isolated from much of the rest of the world.

“I really didn’t see much of Mexico growing up as a Jew,” Cherem said. “I only had Jewish friends. It wasn’t until I went to LA that I realized how big the world is and how much I’d been segregated from it.”

The film includes his ideas for the future and discussions he would like to see happen more often in his community, on subjects like intermarriage, homosexuality and breaking customary boundaries.

While it seems like “Leona” could ruffle some feathers among Mexican Jews, Cherem explained that several members of his community traveled great distances to see his directorial debut at a Mexican film festival.

“I’ve heard from people who haven’t seen it that it’s not good, that it’s making us look bad, that we should keep our problems inside our community,” Cherem said. “But a lot of young people and women, in particular, are very thankful for the film.”

comments