Emory Professor Jacob Wright Thrives on Big Ideas

His new work about the origins of the Bible is already acclaimed as one of the best books of 2023.

No one could ever accuse Emory University Biblical scholar, Jacob Wright, of not having a broad and compelling vision of Jewish belief. The 50-year-old professor of Hebrew Bible in the university’s Candler School of Theology came to Emory partly on the strength of work on a scholarly book about Nehemiah that won the prestigious and richly endowed Templeton Prize 15 years ago. He hasn’t looked back since.

Among his many essays, articles, and books is another prize winner on King David, a pioneering volume that paired the printed text with digital multimedia on the Apple publishing platform. Five years ago, he created an online course on the Hebrew Bible for Coursera, the online university, that has been seen by well over 60,000 of Wright’s students. It has helped to create a worldwide community of study of the Hebrew Bible that has bonded with the popular Emory professor.

Now Wright, who is also an active congregant of the Modern Orthodox Congregation Ohr HaTorah on LaVista Road, has taken a new and distinctly iconoclastic view of the scriptural foundation of Judaism. His new book, “Why The Bible Began,” has been hailed by the New Yorker magazine and Publisher’s Weekly as one of the best books of 2023. It’s likely to be a lively contender for a National Jewish Book Award and other significant prizes.

The book turns on its head the traditional belief that Jewish teachings grew out of the political and spiritual triumphs of the Hebrew Bible. He relegates such stories as the Passover Exodus, the Maccabean successes of Chanukah, and the defeat of Haman, the tyrannical prime minister of Persia at Purim to a largely literary tradition.

In their place, he posits the belief that what we now call the Jewish People was shaped by historical forces brought on by adversity, defeat, and destruction. Specifically, he recalls a period of 100 years or so, between the 7th and 8th centuries.

The 10 tribes of Israel were conquered and obliterated in the north of the country by the Assyrians in 722 BCE and Judah and Jerusalem in the South were menaced and ultimately overcome by the Babylonians in 586 BCE. A new intellectual tradition took root during the period that sought to find a way to survive despite the gloomy prospects of a conquered people.

What he theorizes, based on both historical and archeological courses, is that the intellectuals of the time, the courtly scribes and educated elite of both Israel and Judah, realized the need for a new approach to survival. This new generation of thinkers came to believe that their lack of worldly success might not doom them. A deeper study of their fate they believed, might yet be able to rescue victory from the jaws of defeat. The direct result, Wright says, is our Torah.

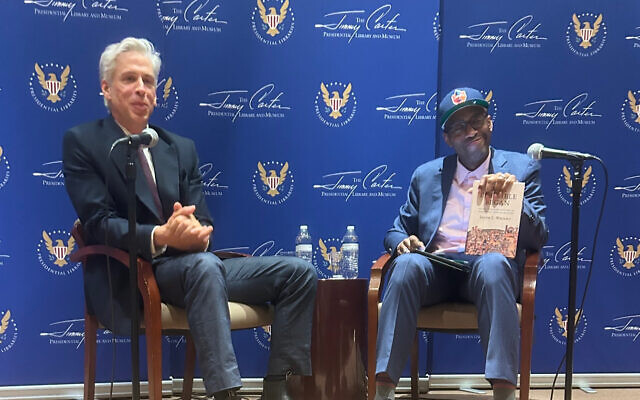

During the book’s formal launch last month at the Carter Presidential Center in Atlanta, Wright described the ancient quest by Jews 2,700 years ago, was nothing less than the search for a new way of being for them in the world.

“If we don’t have that political control in a world in which we are dispersed and exiled and abused,” Wright commented, “how can we be a people who can be a nation? That’s what this national identity is built for in the Bible, not for statehood. It’s a national identity by Jews of being defeated and still being able to survive and live and endure.”

Wright said these new thinkers created a new kind of community among themselves based on ideas and a belief system that couldn’t be overcome by armed might. One that would survive and even thrive in the face of colonization and subservience. The story they wove out of their writings and their collaborative discussions shaped a new story.

It echoed with the belief that the community had to be fundamentally shaped by stories that were woven out of the relationship between a single G-d and that of G-d’s people. Fundamentally, Wright believes that Jews have survived for so long because of how these notions of peoplehood have taken hold among us.

The book, which has been three years in the making, builds on Wright’s previous work in 2020 on “War, Memory and National Identity in the Hebrew Bible.” In it, he writes that the collective memory of a people is most often shaped by the political challenges of war and conflict.

The concept of strength through a common belief in peoplehood, Wright believes, might hold promise for us today. Out of adversity and our belief in a common destiny, he told his Carter Center audience, we may be able to shape a way out of these dark times.

“Let’s hope that something like that emerges. The cataclysmic state of the Middle East right now is probably not much different than it was during the time of the Bible being written.”

Jacob Wright’s “Why The Bible Began,” can be given for Chanukah as an eBook and hardcover. Cambridge University Press. List $34.95

comments