Jewish Music Festival Closes with Salute to the Past

The 2019 Atlanta Jewish Music Festival took a look back at both the roots of popular music in America and the contributions American Jews have made to its growth.

Wrapping up its series of programs, the 2019 Atlanta Jewish Music Festival took a look back at both the roots of popular music in America and the contributions American Jews have made to its growth.

During the closing week of the festival, Executive Director Joe Alterman brought in two authorities on the subject and paid tribute on closing night to the Chess brothers from Chicago, who left a rich legacy in recorded music of the rock ’n’ roll era.

Rabbi Neil Sandler, the senior rabbi at Ahavath Achim Synagogue, launched the final three days of events that began March 14. He noted that Jewish music has a relationship with the holy, the kedushah of scripture. In its biblical origins, he pointed out, Jewish music is holy through its separateness.

“It’s separateness in some regards because it is ours, not just in distance, but in a kind of holiness for us to discover,” he said.

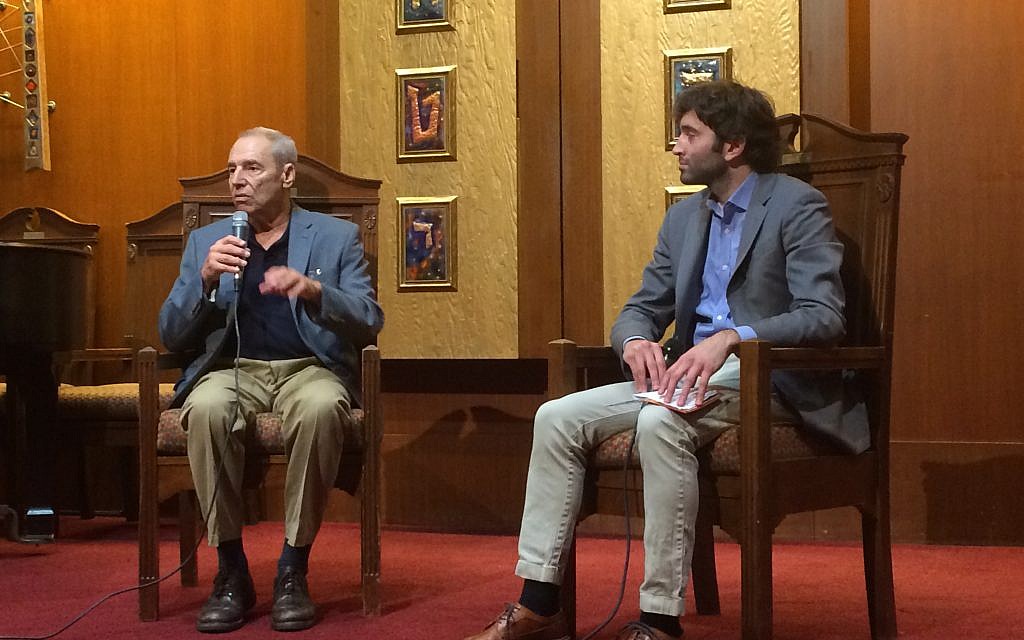

Leading the night’s program of discovery at the synagogue was musician and musical historian Ben Sidran, whose acclaimed 2012 book, “There Was a Fire: Jews, Music and The American Dream, ” is an examination, in one respect, of how Jews explored their separation from American society to form a bond with another important group of “outsiders,” African-Americans.

Sidran’s talk at the AA synagogue echoed his remarks in his book, that “On the one hand, Jews wanted to be Americans totally. On the other hand, they also needed to be the ‘other’ in order to exist as Jews. By identifying with blacks, they were able to accomplish both. Jews were guaranteed to be connected to the true American outsider experience.”

In the process, they were pioneers in both the popularization of black culture in America while at the same time putting their own distinctive stamp on the creation of America’s great cultural export – popular music.

Yet, as Sidran reminded his audience, the immortals of America song, men such as Irving Berlin, George Gershwin and Bob Dylan, were the first to say that being Jewish had absolutely nothing to do with their creative work. But as Sidran pointed out, “There is nothing more Jewish than saying that being Jewish had nothing to do with your music. Because, we are talking about something that is hiding in plain sight.”

The Jewish commitment to social justice and societal change is reflected in one of the first American songs about social consciousness, “Brother Can You Spare A Dime?” which was composed by Yip Harburg in 1932. It was the first of hundreds of such songs that followed, such as Marvin Gaye’s “What’s Going On” in the 1960s and 1970s and beyond.

That commitment to Jewish values and tradition was reflected in comments by the writer and music critic, Alan Light, who was Temple Sinai’s scholar in residence and a guest of the AJMF during the Shabbat weekend March 15-16.

In his series of four talks, Light explored the work of Jewish song writers such as Bob Dylan and the influence of Israel in the work of non-Jewish composers such as Johnny Cash. But it was the work of Leonard Cohen, the Canadian born singer and songwriter, who died in 2016 at the age of 81, that Light found particularly inspirational.

He praised Cohen for his “ability to encapsulate multiple ideas, multiple emotions. This is where you see the discipline, the seriousness of someone who was a poet first,” Light pointed out.

This was most apparent in Cohen’s famous work, “Hallelujah,” his epic song that he worked on during the last 30 years of his life, adding at least 80 verses to the song’s lyrics. In its opening lines, it reminds us of the moral descent of King David as told in the biblical book of Samuel.

“The notion of being attached to history, of art, of creativity,” is at the heart of Cohen’s significant and long-lasting body of work,” according to Light.

This year’s festival concluded with a tribute to the legacy of Chess Records, the recording company founded in 1950 by two Jewish immigrants from what is now Belarus, Fiszel and Lejzor Czyż, who changed their names in America to Phil and Leonard Chess.

They brought to Americans at the beginning of the rock ’n’ roll era such stars as Chuck Berry, Muddy Waters, Bo Diddley and Etta James. During the 25 years the Chesses owned the company, they made their building at 2127 S. Michigan Avenue one of the centers of popular music.

The festival ended with two sold out performances by the ATL Collective that re-created some of the label’s best-known hits.

The extended weekend was a fitting and wide-ranging acknowledgment of the role that Jews have played in creating the world of American popular music. And it was a rousing climax to the change in direction that Alterman emphasized in his first year as the festival head. This includes being more welcoming, expanding the audience and making the experience deeper and more meaningful. He is already looking to the future and how music can expand our understanding of one another.

“I have this idea that I love, that the festival is a gift. It’s a gift that brings people in to share music with others and ultimately, to bring people together around music.”

comments