Jimmy Carter’s Jewish Legacy

The 39th president of the United States has received both praise and reproach from the Atlanta Jewish community.

Dave Schechter is a veteran journalist whose career includes writing and producing reports from Israel and elsewhere in the Middle East.

Paige Alexander first met Jimmy Carter on a cold day in December 1979 as the president welcomed British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher to the White House.

The 13-year-old Alexander was visiting Washington, D.C., with her mother, Elaine. A Georgian working in the White House protocol office arranged for the Jewish Atlantans to attend the South Lawn ceremony.

After Carter (and, less memorably, Thatcher) shook her hand, “I went around Washington the rest of the trip saying I wasn’t going to wash my hand,” Alexander told the AJT.

Alexander and Carter have shared many more handshakes, particularly since June 2020, when she became CEO of The Carter Center, the institution entrusted with continuing his decades of humanitarian, conflict resolution, and pro-democracy work.

“I’ve told him that story,” Alexander said, chuckling that, having assumed that position during the COVID-19 pandemic, she’s washed her hands before taking his.

The legacy of the 39th president of the United States has been the subject of much discussion, including in the Jewish world, since the Carter Center announced Feb. 18 that the 98-year-old had entered hospice care at his home in Plains, Georgia.

The devout Baptist built ties within Atlanta’s Jewish community that contributed to his election as governor in 1970 and as president in 1976.

Carter is remembered for the Camp David Accords that produced a peace treaty between Israel and Egypt, and for books and statements critical of Israeli policies regarding the Palestinian Arabs.

Carter advocated for the right of Soviet Jews to emigrate, promoted increased testing for Tay-Sachs disease, established the President’s Commission on the Holocaust (which led to construction of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum) and, during the Iran hostage crisis, enabled Jews and other religious minorities leaving that country to enter the U.S.

Despite Jewish opposition, he pushed through the sale of F-15 fighter jets to Saudi Arabia (in a package deal with fighter jets for Israel and Egypt), and his ambassador to the United Nations, Atlantan Andrew Young, resigned after misleading the State Department about an unauthorized meeting with an official of the Palestine Liberation Organization.

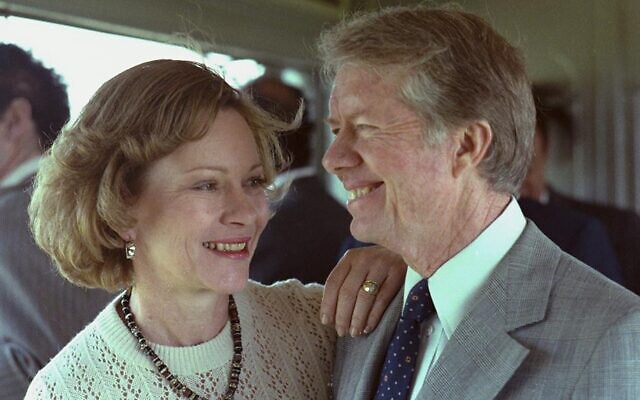

Carter is revered for the work of the Atlanta-based center that bears his name (receiving the Nobel Peace Prize in 2002) and for his (and his wife, Rosalynn’s) stamina building houses with Habitat for Humanity.

Rabbi Emeritus Alvin Sugarman of The Temple recalled being introduced to Carter, before he was a presidential candidate, at a Shabbat dinner hosted by Atlanta attorney Robert Lipshutz, who went on to serve as national campaign treasurer in 1976 and later as White House counsel.

Carter was “as gracious and generous and caring a human being as you’d ever want to know,” Sugarman said. “I think his life has been a reflection of the highest ideals of the Judeo-Christian understanding of what it means to be a child of G-d. His life was rooted in a prophetic understanding of looking at the world through G-d’s eyes and what the prophets yearned for, a world of justice.”

In 1976, though, Carter’s brand of born-again, evangelical Christianity made some Jews nervous.

The Southern Israelite (now the Atlanta Jewish Times) endorsed Carter in an April 1976 editorial that said: “Knowing him personally for these many years, we have grown to admire his decency, his forthrightness, his innovativeness, his compassion and willingness to tackle the nitty-gritty of government. He has demonstrated a scope and a vision which places him head and shoulders above many [in] contemporary politics.”

Carter received an estimated 71 percent of the Jewish vote in defeating Republican Vice President Gerald Ford.

At his inauguration, on Jan. 20, 1977, “The Star-Spangled Banner,” was sung by Cantor Isaac Goodfriend of the Ahavath Achim Synagogue, who called it “one of the highlights of my life,” in an interview for the Georgia World War II Oral History Project.

Jews Among Carter’s ‘Georgia Mafia’

The Jewish members of the “Georgia mafia” in the Carter White House, included Lipshutz; Stuart Eizenstat, chief White House domestic policy adviser, Steve Selig, Deputy Assistant to the President and chief liaison with the business community; and Gerald Rafshoon, Assistant to the President for Communications. The four had worked on Carter’s gubernatorial and/or presidential campaigns.

“No American President has done more to advance the security of the state of Israel, champion the rights of the Jewish people around the world, memorialize the victims of the Holocaust and honor its survivors, and embody the Jewish tradition of tikkun olam, repairing the world, than Jimmy Carter, a devout Southern Baptist from the tiny hamlet of Plains, Ga. And none were less rewarded politically by the American Jewish community for doing so,” Eizenstat wrote in an op-ed published Feb. 23 in the Forward.

Rafshoon, an advertising executive and creative director who produced television ads for Carter’s successful gubernatorial and presidential campaigns, recounted an early encounter in Plains.

“Carter said, ‘You’re Jewish, aren’t you?” Rafshoon told the AJT. After establishing that Rafshoon was Jewish, Carter asked, “Do you my Uncle Louie?” Rafshoon did not but learned that Louis Braunstein, the only Jew that Carter knew growing up, was an Atlanta native, an insurance salesman married to one of Carter’s aunts, and lived in Chattanooga.

Carter “was a religious guy, but never tried to force it on anybody,” he said.

Selig recalled going with his father to the Commerce Club to have lunch with presidential hopeful Carter. They had not supported his 1970 gubernatorial run and knew little about him.

“I’ve never been more impressed with anyone in my life than I was with Jimmy Carter that day. He had this knowledge, and continued to have this knowledge, on every single subject, including when I worked with him in the White House,” said Selig, who also served as deputy campaign director in 1976 and chair of the 1980 re-election campaign.

Selig told the AJT that no matter what business group that he brought into the White House, Carter made himself available and “had knowledge of the subject matter . . . that would be everybody from motion picture executives to retailers to truck stop operators.”

Carter’s March 1977 endorsement of a Palestinian “homeland” rattled Jewish supporters. A memorandum that June from White House Chief of Staff Hamilton Jordan warned: “I think it is accurate to say that the American Jewish community is extremely nervous at present. And although their fears and concerns about you and your attitude toward Israel might be unjustified, they do exist. In the absence of immediate action on our part, I fear that these tentative feelings in the Jewish community about you (as relates to Israel) might solidify, leaving us in an adversary posture with the American Jewish community.”

Camp David Breakthrough

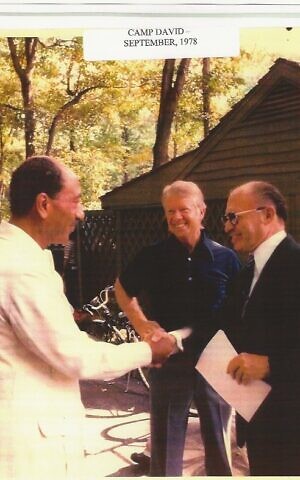

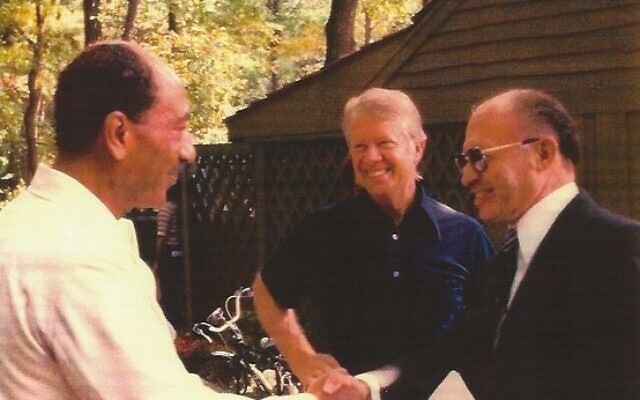

The high points of Carter’s presidency were reached in September 1978 with the Camp David Accords and in March 1979 (after months of negotiating the details) with the peace treaty signed by Israeli Prime Minister Menachem Begin and Egyptian President Anwar Sadat at a White House ceremony.

“Being at the Begin-Sadat peace treaty [signing] at the White House, sitting there in front of them, watching them shake hands, and with Jimmy Carter, that that was pretty meaningful,” Selig said in an oral interview for the Cuba Archives for Southern Jewish History at The Breman Museum.

Rafshoon recounted the moment credited with changing the course of the on-again, off-again Camp David negotiations. Susan Clough, Carter’s personal assistant and White House secretary, brought her boss photographs of Carter with Sadat and Begin and of Carter with Begin.

“He grabbed the pictures. I followed him up to Begin’s cabin,” where, Rafshoon said, Begin told Carter, “I’m sorry, it’s not going to work out.”

Rafshoon said that Carter replied, “It’s okay, I brought you these pictures for your grandchildren.”

As Begin recited their names, Carter signed the photographs. “He says, ‘I was hoping to be able to write that this is when your grandfather and I brought peace to the Middle East,'” Rafshoon said. “Begin burst into tears.” One more, ultimately successful, effort was made. “I was the only person besides Jimmy in the room.”

Mired in the Iranian hostage crisis and a slumping economy, Carter lost his November 1980 re-election bid to Republican Ronald Reagan, receiving the lowest percentage of Jewish votes by a Democratic presidential candidate since 1920.

Speaking in November 2018 at the Book Festival of the Marcus Jewish Community Center of Atlanta, Eizenstat called Carter “the most accomplished and under-appreciated first-term president in American history.”

Carter’s Israel Controversy

Carter’s post-White House criticism of Israel brought him stinging dose criticism from much of the Jewish community, including from previous supporters and associates. [Compared with the Southern Israelite’s 1976 endorsement, an April 2015 AJT editor’s notebook labeled him a “parasite.”]

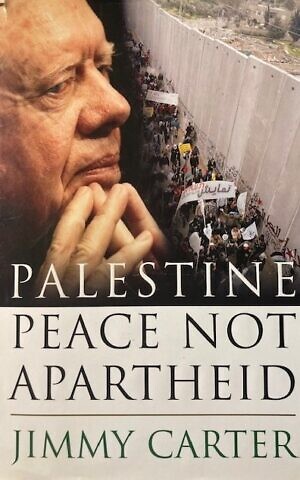

The title of his 2006 book — “Palestine Peace not Apartheid” — prompted comparisons of Israel to South Africa’s pre-1994 racial separation laws. His comments during a book tour, that the “pro-Israel” lobby had impeded pursuit of an even-handed U.S. policy in the Middle East, added to the upset.

Saying that he felt “betrayed,” Emory University Prof. Kenneth Stein, executive director of the Carter Center from 1984-86 and an adviser on Middle East affairs, resigned as Middle East Fellow at the Center in December 2006, ending his association with the institution.

In January 2007, 14 Atlanta Jewish business and civic leaders resigned from the Center’s Board of Councilors, an advisory body of some 200 people. “It seems you have turned to a world of advocacy, even malicious advocacy,” they wrote in a letter. “We can no longer endorse your strident and uncompromising position. This is not the Carter Center or the Jimmy Carter we came to respect and support. Therefore, it is with sadness and regret that we hereby tender our resignation from the Board of Councilors of the Carter Center effective immediately.”

Their letter read: “Your book has confused opinion with fact, subjectivity with objectivity and force for change with partisan advocacy. Furthermore, the comments you have made the past few weeks insinuating that there is a monolith of Jewish power in America are most disturbing and must be addressed by us. In our great country where freedom of expression is basic bedrock you have suddenly proclaimed that Americans cannot express their opinion on matters in the Middle East for fear of retribution from the ‘Jewish Lobby.'”

Carter told National Public Radio: “This is the first time that I’ve ever been called a liar, and a bigot, and an anti-Semite. This has hurt me.”

Among those who resigned from the Board of Councilors was Selig, who received a handwritten letter in which Carter said, “I’m sorry you felt like you had to resign. I understand why you did it. You’ll always be my friend.”

“I think Jimmy Carter was absolutely, totally, 100 percent not antisemitic or anti-Israel. I think he was doing what he thought was best to bring peace to the Middle East. It was one of the great honors of my life to work in his administration,” said Selig, who used the words “honesty and integrity” to describe Carter.

I think Jimmy Carter was absolutely, totally, 100 percent not antisemitic or anti-Israel. I think he was doing what he thought was best to bring peace to the Middle East. It was one of the great honors of my life to work in his administration.

“Carter doesn’t have prejudices,” Rafshoon said, before pausing and adding, “I think his prejudices might be, you’re for me or against me.”

Carter sought a measure of forgiveness in December 2009, referencing a Yom Kippur prayer. “We must recognize Israel’s achievements under difficult circumstances, even as we strive in a positive way to help Israel continue to improve its relations with its Arab populations, but we must not permit criticisms for improvement to stigmatize Israel,” he wrote in an open letter. “As I would have noted at Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur, but which is appropriate at any time of the year, I offer an Al Het for any words or deeds of mine that may have done so.”

Historian Steven Hochman, who has worked with Carter for 40 years, said, “I didn’t like the title” of the book, but that in the text, “He never accused Israel of being an apartheid state,” instead cautioning that “if you don’t make peace with the Palestinians, the danger is that you will have an apartheid state, and numerous Israelis have said the same thing.”

Carter “believes that he was acting in the interest of Israel in everything he did, and that if Israel had followed, if the leadership had followed him, there would have been peace in the Middle East, at least between Israel and its Arab neighbors,” Hochman, the Center’s Director of Research, told the AJT.

Looking Back at Camp David

Alexander said that in a September 2021 phone conversation, Israeli President Isaac Herzog “thanked Carter for his key role in Israel’s first peace agreement with an Arab county. The fact that President Herzog was able to look back at what President Carter did for the state of Israel, and the safety and security that Israel has had for the 40 years, I think that this is President Carter’s lasting legacy with Israel.”

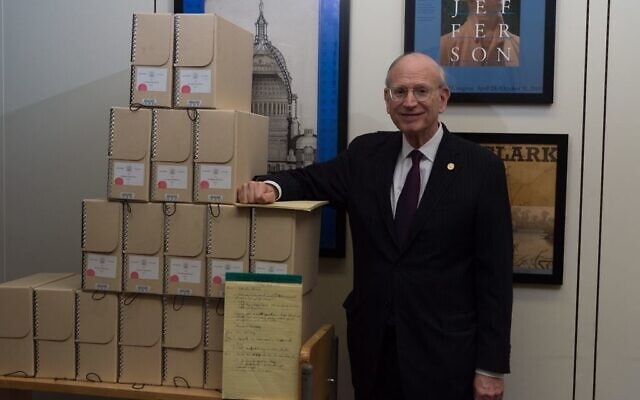

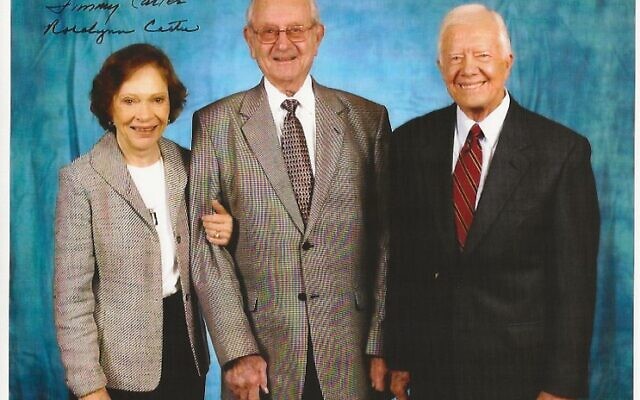

Lipshutz, who died in 2010, compiled notebooks about his involvement with Carter on Middle East issues, including photographs and documents. One photo, labeled “Passover, 1977/“The First Seder,” showed Lipshutz at the head of the table with Jimmy and Rosalynn Carter to his right.

The notebooks include a memorandum that Lipshutz dictated on March 13, 1979, as Air Force One returned from Israel and Egypt. “Perhaps incorrectly, I feel that one of the reasons which has made Jimmy Carter so tenacious in his efforts to bring about this peace in the Middle East, even though probably subconsciously, is his relationship with me, personally,” he wrote. “Obviously there are even more compelling reasons for him to have done so, but it is a source of tremendous satisfaction to me that I have this particular feeling and it makes a lot of the effort of the past four or five years worthwhile . . . And, it also makes the ‘slings and arrow’ of the last two years, particularly from Jewish people and Jewish groups, lose their sting and dull the pain.”

When Lipshutz stepped down as White House counsel on Oct. 1, 1979, Carter wrote to him: “It is with deep personal regret and a sense of loss that I accept your resignation . . . There is no way I can adequately express my appreciation to you for your sound personal and official advice to me.”

- News

- politics

- Dave Schechter

- Paige Alexander

- Jimmy Carter

- British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher

- White House

- Carter Center

- COVID-19 pandemic

- Camp David Accords

- Commission on the Holocaust

- Andrew Young

- Palestine Liberation Organization

- Nobel Peace Prize

- Habitat for Humanity

- Rabbi Emeritus Alvin Sugarman

- The Temple

- Robert Lipshutz

- Gerald Ford

- Ahavath Achim Synagogue

- Cantor Isaac Goodfriend

- Stuart Eizenstat

- Steve Selig

- Louis Braunstein

- Hamilton Jordan

- Commerce Club

- Israeli Prime Minister Menachem Begin

- Egyptian President Anwar Sadat

- The Breman Museum

- Cuba Archives for Southern Jewish History

- Ronald Reagan

- Marcus Jewish Community Center of Atlanta

- Steven Hochman

comments