Links Between Zionism and Human Rights Movement

Emory's annual Rothschild Memorial Lecture tackled the hot-button issue of human rights and the often-forgotten role that Jews and Zionism played.

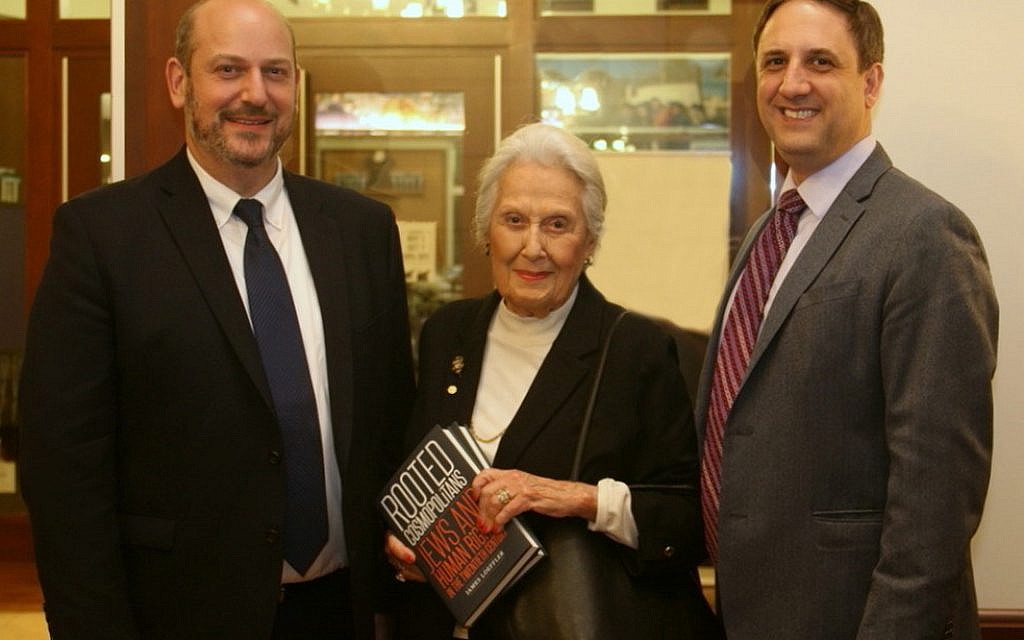

Last week’s annual Rothschild Memorial Lecture at Emory University tackled the hot-button issue of human rights and the often-forgotten role that Jews and Zionism played in the difficult modern quest for equality and justice in the world.

Guest lecturer at the Nov. 15 event, James Loeffler, professor of Jewish history at the University of Virginia, pointed out that the state of Israel and the modern human rights movement were launched at almost the exact moment 70 years ago.

It was about the same time, in the late 1940s, that Rabbi Jacob Rothschild, for whom the memorial lecture is named, took over the leadership of The Temple in Atlanta. He and many of his contemporaries quickly became deeply involved in the national debate about civil and human rights during the post-war years.

“Human rights may have a long pedigree in human civilization,” Loeffler pointed out, “but as we know them, they really came into their own after World War II, when the U.N. began to introduce a new idea of taking principles of human dignity, justice and rights, and transforming them into a system of human law.”

The words of Israel’s Declaration of Independence were uttered just months before the U.N.’s Universal Declaration of Human Rights was created. Not coincidentally, a number of Jewish human rights advocates were involved in the creation of both.

He describes them in his new book, “Rooted Cosmopolitans: Jews and Human Rights in the Twentieth Century,” which inspired the Emory lecture, as being rooted in the nationalist ideas of the Zionist movement, while, at the same time, deeply committed to the cosmopolitan ideal of human rights for all mankind.

Among the more important figures in the human rights debate in the 1960s and 70s was the Georgia-born civil liberties attorney, Morris Abram, who was a leader in the American Jewish community during the second half of the last century.

He was president of Brandeis University in its early years, before going on to become the youngest national president of the American Jewish Committee, chairman of the National Conference on Soviet Jewry, and chairman of the Conference of Presidents of Major American Jewish Organizations.

But as a strident advocate of civil liberties, he had the challenging task of attempting to extend the early successes of the human rights movement at a time when the United States was deeply involved in the battle for racial equality.

According to Loeffler, Abram believed that the success America was having in extending equal rights to African-Americans in the 60s might also inspire progress at the United Nations.

“When the civil rights movement is beginning to realize the promise of equality,” Loeffler said of Abram’s beliefs at the time, “he thought that maybe we could do the same thing at the United Nations with anti-Semitism.”

But despite a concerted effort by Abram, American diplomats and others, the human rights battle fell victim to the Cold War rivalries between the United States and the Soviet Union.

In an ironic turn of events, those Jews fighting to extend progress in human rights and to combat anti-Semitism found the issue turned against them. In a highly successful diplomatic offensive, the Soviet Union and its Arab allies at the U.N. successfully made Israel and its treatment of the Palestinians a human rights issue.

In 1975, the U.N. adopted Resolution 3379, which condemned Zionism as a form of racism and racial discrimination.

After decades of attempting to reform the human rights movement at the U.N., the United States earlier this year withdrew from what Ambassador Nikki Haley called a “hypocritical and self-serving” United Nations Human Rights Council, particularly in its chronic bias against Israel.

comments