Lynching Memorial Commemorates Georgia Victims

A new granite marking is believed to be the only memorial in Georgia addressing lynchings that took place throughout the state.

Dave Schechter is a veteran journalist whose career includes writing and producing reports from Israel and elsewhere in the Middle East.

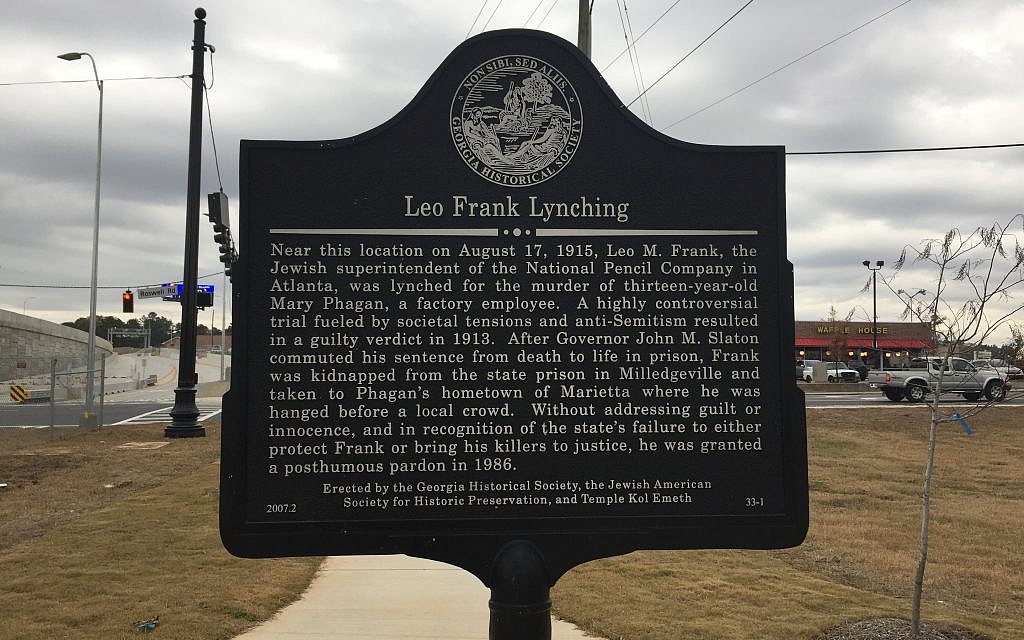

On Roswell Road in Marietta, bordered on one side by a restaurant parking lot and on the other by Interstate 75, is a strip of grass and shrubbery with a sidewalk that leads to two memorials.

Leo Frank, a Jew, was lynched on August 17, 1915, in a nearby woods long since cleared and built over. His memorial, a plaque affixed to a pole, was rededicated in August after being removed four years earlier for road construction.

Several feet away is a recently installed black granite slab, believed to be the only memorial in Georgia addressing lynchings that took place throughout the state.

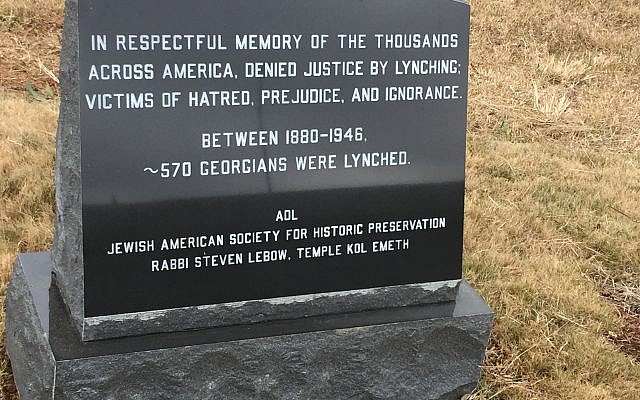

The inscription reads:

In respectful memory of the thousands across America, denied justice by lynching: Victims of hatred, prejudice and ignorance.

Between 1880-1946,

~570 Georgians were lynched.

ADL

Jewish American Society for Historic Preservation

Rabbi Steven Lebow, Temple Kol Emeth

The benefactor for the lynching memorial, as for the Leo Frank plaque, is Jerry Klinger, a 70-year-old retired financial services executive from Rockville, Md., and founder of the Jewish American Society for Historic Preservation. JASHP has put up historic markers on dozens of sites nationwide, and in several countries.

In 2016, Klinger told The Forward (in an article written by the author), “The marker projects go to create simple visible facts on the ground. They create visible affirmation of forgotten history of American Jewish legitimacy and commonality as Americans. The markers affirm the incredible experience of American Jews and Jews as Americans. In mass cultures, where the Mona Lisa is appreciated by millions of visitors in 15 seconds or less, the markers are extremely effective.”

Klinger had a succinct answer when asked by the Atlanta Jewish Times why a memorial to lynchings in Georgia was being created and funded by someone from outside the state. “Frequently those nearest the trees can’t tell it’s a forest,” he said.

Lebow has been a leader in efforts to remember Frank and press for his exoneration of a 1913 murder conviction in the death of 13-year-old Mary Phagan, who worked at the Atlanta pencil factory where Frank was the superintendent. Cobb County residents, angered by Gov. John Slaton’s commutation of Frank’s death sentence, kidnapped Frank from the state prison in Milledgeville, drove him to woods near what is now Frey’s Gin Road and, early on the morning of August 17, 1915, hanged him from a tree.

In a statement, the Atlanta regional office of the Anti-Defamation League said: “This memorial is the first to recognize all victims of lynching in Georgia. That makes it very significant. The placement of the memorial at the Leo Frank historical marker is very appropriate. ADL’s founders recognized through our mission that you cannot just fight hate against Jews but must speak out no matter who is targeted by hateful acts. While Leo Frank is the one Jewish lynching victim we are aware of, there were thousands of African Americans and others lynched, not just in Georgia, but across the country.”

By some estimates, as many as 95 percent of those lynched in Georgia were African-American.

Klinger had hoped to make the memorial national in scope, but what has been installed is what the Georgia Department of Transportation, which controls the site, would approve, he said. The memorial – 36 inches tall, 14 inches wide at its base and six inches in depth – was crafted to Klinger’s specifications by the Roberts-Shields Memorial Company in Marietta. Steel pins have been inserted to make the memorial resistant to vandalism.

A formal dedication of the lynching memorial may take place next August.

Klinger said the number of Georgians lynched came from Dana Chandler, the university archivist at Tuskegee University in Alabama. Klinger has been working with Chandler to create and place markers on a Tuskegee civil rights trail.

The reason for the use of the “~” figure on the memorial is because the documented number of lynchings in Georgia may be incomplete, Klinger said.

A report issued in 2017 by the Equal Justice Initiative identified 4,084 “racial terror lynchings” in 12 Southern states, and 300 in other states, between 1877 and 1950. Among the states, Georgia, with 589, was second only to Mississippi’s 654. According to EJI, the largest number in any Georgia county, 37, was in Fulton County, many taking place during the September 1906 Atlanta race riots.

The EJI is the organization behind The National Memorial for Peace and Justice and The Legacy Museum: From Enslavement to Mass Incarceration, in Montgomery, Ala.

The 1946 date on the newly installed memorial is connected to the Moore’s Ford lynchings, the shooting deaths on July 25 that year of two married African-American couples – George W. and Mae Murray Dorsey, and Roger and Dorothy Malcolm – in Walton County, Ga., in the area of Moore’s Ford Bridge. The case attracted national attention and prompted the introduction of anti-lynching legislation that failed to pass in Congress. The state of Georgia and the FBI closed the case in December 2017 with no one ever prosecuted.

comments