My Bar Mitzvah’s Gone By

Two Jewish Atlantans, ages 98 and 81, share the story of their bar mitzvahs and how they are tied to Jewish history in Europe.

We asked two Jewish Atlantans, ages 98 and 81, to reminisce about their bar mitzvah long ago in Naples, Italy and Budapest, Hungary, respectively. Their stories are woven with our rich Jewish history, with fascism, communism, the Depression, Kristallnacht and the Holocaust.

Tradition During Depression

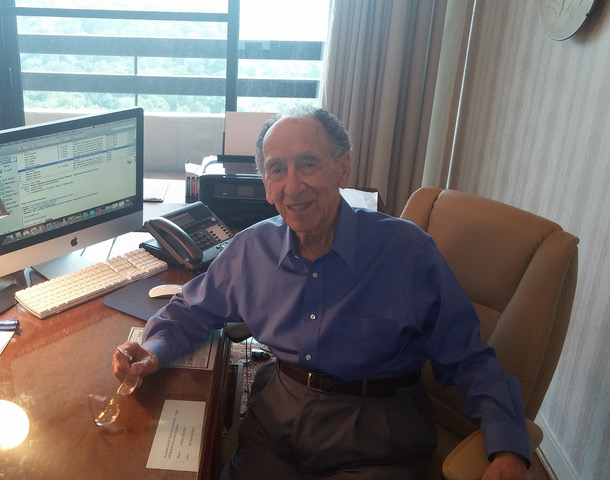

Mario Foah had his bar mitzvah in Naples in March of 1934. He has lived in Atlanta for 26 years, retiring here after a successful career in the food industry. He loves this Southern city, and lives, at 98 years old, perfectly independently in his apartment in Buckhead, where I met him. He writes, listens to music, receives his friends and is planning a trip to Italy in October.

With the exception of driving, nothing stops him. On his 90th birthday, he decided to never drive again.

“It has been a long time since I shared this memory. It was more than 85 years ago, at the synagogue in Naples, Italy. So long so, that even my son, Robert, didn’t know, until now, if I had my bar mitzvah. ”

He told of this recollection: We are Italian Jews, who escaped from Spain after the persecution of the Spanish Inquisition. After a brief stay in Holland at the beginning of the 18th century, my mother’s family emigrated to southern Italy, while my father’s parents had lived in the north for generations, near Milan.”

My parents met in Naples, where my father, a businessman, 28 years old, fell in love with the 18-year-old daughter of the rabbi of Naples. My grandfather was the head of the Jewish community of 600 people. By marrying my father, my mother abandoned kashrut and the observance of the Sabbath, however, we went to the synagogue on Rosh Hashanah and on Yom Kippur.

When the time came to celebrate my bar mitzvah in 1934, my father was recovering from the 1929 economic crisis. He had gone bankrupt, and rather than saving whatever assets were left for his family, he sold everything we had in order to pay off his customers. He wanted to be able to walk with head held high.

Anyway, even if we had stayed rich, like before the Depression, my bar mitzvah would not have been lavish. It wasn’t the custom. It was a rite of passage, and above all, the tradition. So, even for my parents, who were rather emancipated and steered away from religion, it was unthinkable not to have a bar mitzvah. So I studied every single day for a year with my grandfather, while my grandmother, born in Egypt, made me french fries every afternoon, which I ate in her kitchen, secretly from my mother.

On the day of my bar mitzvah I wore a tie, and I have to admit that since then, I have been wearing a tie every day. We were about 50 people, mainly the family. After the ceremony, we all went to my grandparents’ small apartment, next to the synagogue, to eat some honey pastries. I received books as gifts because people knew I wanted to be a teacher of Latin and Greek, a path I never pursued.

During the year I spent with my grandfather, when I asked him for advice about my future, he said to me to follow my path: Leh Leha, as one of the [parashot] said, ‘Go for yourself.’ By 1934, we were perfectly integrated into Italian society, and the arrival of Mussolini did not frighten us. This changed in 1938. When I was supposed to go to university, I was denied access not only to my studies, but to the building itself. I joined an uncle in Chicago, abandoning my family from which I had no news for four years. I went ‘for myself’ but the price I had to pay was high.

My parents have always respected my choices. I respected my children’s choices. My older son had his bar mitzvah in New York, at the Spanish synagogue, which practices the same rites that we had in Italy. But my second son didn’t want to do his bar mitzvah, and I never pushed him. It would never have occurred to me. But these days, I find that [b’nai] mitzvah have become great shows. One of my cousins celebrated her grandson’s bar mitzvah for three days. What’s the point? What can we learn from this? I still remember the beautiful gift my grandfather, the rabbi, gave me when he told me: “Now you can be part of the minyan. You are a man.”

Ceremony Goes On

Robert Ratonyi had his bar mitzvah in Budapest in January 1951. He and his wife Eva were about to leave for a trip back to his homeland when I asked him to remember his bar mitzvah. Coincidentally, during this trip, he was going to visit the synagogue where he celebrated that occasion.

A few years ago, he began to write his memoirs that cover the first 26 years of his life, a long-term endeavor he hopes to publish before the end of the year. It will be titled “My Journey from Nazism and Fascism through Communism to Freedom.”

He Spoke of his memories: I am 81 years old. I was born in 1938, the year of the Kristallnacht. My father told my mother that he would not want another child brought into this world. Times had become too dangerous for Jews. He was right. The last time I saw my father I was 4 years old.

At the end of the war, as survivors, my mother and I handled the crisis of the Holocaust, as did most of the other survivors: with total silence, trying to rebuild our lives in a country with an uncertain future.

The Communists took power in 1948. My childhood was rocked by the Shoah, my adolescence by communism. 1951 was the year of my bar mitzvah. Stalin was still in power in Moscow, and Hungary was in the hands of the Stalinist dictatorship. To practice religion was extremely difficult, for everybody, Jews as Christians, but we still used to go to the synagogue for the holidays.

My mother worked in a factory and woke up at 6 in the morning. I knew that even as a child, I had some responsibility to shoulder my mother’s burden of hard physical labor. Very early on, because I was fatherless, I became a man of responsibility. And that is exactly what Rabbi Kalman said at my bar mitzvah January 11, 1951, in the Great Synagogue of District X of Budapest, where we gathered.

In fact, there were very few members of my family. At that time, it was dangerous to attend churches and synagogues, but I did not understand the absence of my Uncle Laci, my mother’s older brother. I had no male family member present at this important event of my life. My mother found a lame excuse to explain his absence, but she was also disappointed.

Rabbi Kalman took me under his wing. He was physically impressive, very tall, with a big white beard, and very handsome. He had a 16-year-old daughter, who was also beautiful. There was no big party nor celebration at my bar mitzvah. The whole ceremony probably lasted no more than 20 minutes. I had to read and chant a parashah, which I did rather well. At the end of the ceremony, Rabbi Kalman gave me a prayer book so precious to me, that I still have it today. In it there was a note in Hungarian written by him that said the following:

“First advice: Try to recover from the wounds inflicted on you.

“Second advice: Depend on yourself to make up for what the mad devastation of the evil years deprived you: a father and his advice. Depend on yourself to harden your own character, to develop your own principles.

“Third advice: Trust yourself. I have known you for years. Look at me! Promise me that you will always be a truly good man. My son, let this prayer book be your life’s guide and source of strength.”

My response was a short speech. The word ‘responsibility’ appears at least three times in my speech of only 14 lines! Since that day, I have tried to face my responsibilities.

In 1956, when the Red Army invaded Budapest, I escaped from Hungary to Canada.

I arrived as an immigrant in February 1957 in Canada because the quota of Hungarian immigrants in the United States had been reached. In 1961, I was accepted as a junior (third year) at MIT, where I completed my undergraduate and graduate studies in 1964. I married Eva in 1963 and got my green card in 1964. I had a very successful business career. It was my last job at Contel Corporation in 1978 that brought me to Atlanta.”

comments