New Book Probes Pope’s Silence During Holocaust

David Kertzer’s bestseller is the first to be based on the release in 2020 of the pontiff’s secret wartime archives.

“The Pope at War” is Pulitzer Prize-winning author David Kertzer’s searing new indictment of Pope Pius XII’s timid response to the Holocaust and the atrocities committed by Adolf Hitler and Italian dictator Benito Mussolini.

Kertzer, who teaches Italian Studies at Brown University and has previously written several well-received books about the history of relations between Jews and the Church, skillfully guides readers through the twists and turns in the Vatican’s diplomatic strategy, which largely avoided any outspoken criticism of the Nazis. Nor, for that matter was Pope Pius XII critical of Mussolini and his Black Brigades in Italy where, as the Bishop of Rome, he was the titular head of Catholic Church.

Pope Pius XII said nothing publicly, even in mid-October of 1943, during the Jewish holiday of Sukkot, as German SS officers began their Judenoperation in Rome to round up and deport Italian Jews to Auschwitz. Kertzer makes clear that because the pontiff had never challenged Italy’s laws depriving the Jews of their civil and legal rights nor spoken out against the systematic murder of millions of Jews in Europe, it was not altogether surprising that he remained silent while Rome’s Jews were taken from their homes.

He remained silent even as they were transported to the military college along the banks of the city’s Tiber River, a few hundred yards from the Vatican. Only 16 of them, according to Kertzer, survived Auschwitz.

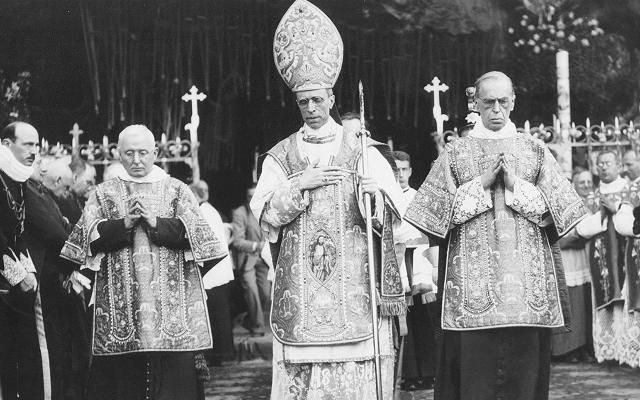

Although his book deals mostly with Pope Pius XII, who assumed the papacy in 1939, on the eve of war in Europe, Kertzer made clear in an interview that the pontiff’s silence was deeply rooted in church history.

“The persecution of the Jews, which began in the thirties, in many countries, including not just Germany but Italy, Poland, Romania, Hungary and elsewhere, all relied on the precedent of the Catholic Church,” he said. “I mean, they largely duplicated the antisemitic measures that the popes themselves had put into place in the papal states for the hundreds of years that they ruled over Jews.”

Moreover, according to Kertzer, the Vatican itself “has been totally unwilling to come to terms with this history.” It was only in early March 2020, for example, that Pope Francis finally opened up the secret archives of Pope Pius XII.

Kertzer’s book is the first to incorporate new revelations about what religious leader and officials in the Vatican did or failed to do during the war years. Among the new revelations is the response by the pope’s adviser on Jewish issues, Monsignor Angelo Dell’Acqua, to the demand that the pope should speak out publicly about the fate of the Jews in Rome.

“Dell’Acqua says, ‘no, we should not be protesting, not even making oral protest,’” Kertzer said. “They weren’t even talking about any kind of public protests. This is all going to be private and Dell’Acqua gives us various antisemitic reasons for why they shouldn’t. He says Jews complain too much and so on. So this is all now known just because of the opening of the archives two years ago. We knew a lot. We knew, basically what the pope did or didn’t do publicly, but why he did what he did and what advice he was given and what was being said in private to him by his advisers is new.”

In Kertzer’s opinion, Pius XII’s silence throughout most of the war was due to his fear, even as late as the round-up of Jews in October 1943. He was fearful for the future of the church in Italy and especially with maintaining the church’s relations with German Catholics. The pope, Kertzer says, was afraid that they might interpret a campaign of hostility toward the Nazis as a reason to set in motion a major break with the Catholic Church, much as the Protestant Reformation had been set in motion by Martin Luther in the 15th century.

“He was afraid, as I found out from the documents in the newly opened Vatican archives, that if he were seen as doing anything to end Mussolini’s regime and this helped lead to the fall of the Axis powers, German Catholics would blame him for their loss, and this would have a very negative impact on the influence of the Vatican and perhaps in Germany and perhaps produce a new schism with the Reformation still in the minds, of course, of churchmen,” the historian said.

So Pius XII ignored repeated pleas by America and its allies to take a stand against the Nazis and their genocidal campaign, which they pursued with single-minded determination in every country they occupied. Instead, the pope stayed quiet and focused his rhetoric on matters of faith, speaking in lofty tones about the virtues of peace and the “fruit of charity and justice.”

As Kertzer points out, the Catholic Church at the end of World War II effectively scrubbed clean the effects of its silence and, in the years after Pope Pius’s death in 1958, began a campaign to put the wartime pontiff on the road to sainthood.

comments