Novel Spotlights Love in Atlanta’s Sephardic Community

Jeanie Franco Marx's "Dayenu" is set in 1930s Atlanta and is based, in part, on her parents, Jack and Catherine.

Jeanie Franco Marx’s new novel, “Dayenu,” is subtitled “A Sephardic Story,” but the author, who grew up in Atlanta, readily admits she left an important word out of that description. That word — and indeed the theme of this book of Jewish family life — is love. “Dayenu” is a Sephardic love story, with equal emphasis on all three words.

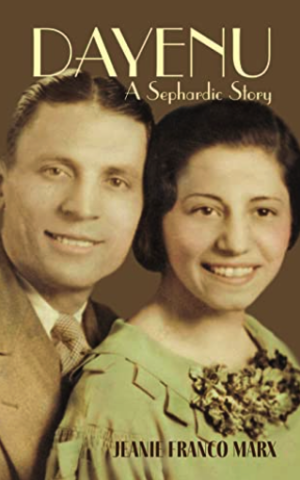

Peering out from the cover of the book is a softly tinted photograph of a smiling, attractive couple, taken 90 years ago. This is an image of Marx’s parents, Jack Franco and Catherine Benbenisty, taken just before they married in 1933. In her book they become Yacov and Malka.

Jack had arrived in the U.S. in 1924, among the last of a torrent of immigrants — including those who left the eastern Mediterranean — to take advantage of America’s liberal immigration laws. Catherine, likewise, was the daughter of immigrants from Rhodes, who found in Atlanta a haven from Europe’s wars and social upheavals.

In “Dayenu,” Marx lifts the curtain that often separated Sephardic Jews from their Ashkenazi neighbors in the heavily Jewish neighborhood just south of the state Capitol in downtown Atlanta. Marx, who married Ashkenazi men, said her first husband had never heard the word Sephardic until he met her. In her parents’ and grandparents’ days, there wasn’t much mingling between the two communities, which often had only the Hebrew language in common. Both had their own synagogues and their own languages (Yiddish and Ladino), which, Marx says, kept them apart.

“It was just such a separate way, a separate existence, it was very different. It was also very isolating I think for the Sephardic community here and probably elsewhere, I’m sure. There certainly were other Sephardic communities across the country that felt the same way.”

Aside from their differences in synagogue worship and religious customs, it was in the events leading up to marriage and the traditions that surround the ceremony itself that most distinguished Sephardic Jews from Ashkenazim.

In the banyo, or the bride’s visit to the mikvah before her marriage, the ritual is festive. As Marx points out in her book, it was followed by a party with female friends and relatives. Strong Turkish coffee was served along with pastries including wedges of masapan, marzipan-like sweets made from almond paste, with three tiny silver balls pressed into each.

Unlike a traditional Orthodox Ashkenazi wedding, where the bride and groom are expected to fast before the ceremony, the prenuptial dinner, as described in “Dayenu,” is festive and includes the toast: “Salud, amor y pesetas y tiempo degastarlas.” May you have love and money and the time to spend it.

Prior to the ceremony at a Sephardic wedding, there was no bedeken, the Ashkenazi veiling ritual in which the groom appears before his bride and covers her face with a veil. Nor was there a chuppah, with four poles supporting it. Instead, the couple stands under the groom’s wedding tallit, which is held aloft.

The bride doesn’t circle her husband seven times during the ceremony, nor do they take a break — called the yichud — to be alone following the ceremony. In some instances, the couple uses that time together to break their pre-nuptial fast and even to have their first sexual encounter.

As Marx relates in her book, some marriages in the Sephardic world in Europe involved child brides. Her grandmother told her the story of how she was married off in Turkey at the age of 13 and had to wait until she was sexually mature three years later for the betrothal to be consummated.

For Marx’s heroine, the young Malka, who is married not too long after her high school graduation, the whole process of courtship leaves her somewhat bewildered. For all the festivity surrounding the nuptials, the character — based on her mother’s experiences — doesn’t feel any bells go off, as she puts it.

“She wasn’t sure she was in love when she accepted Yacov’s proposal. And it was something that grew over time. She knew that there were still going to be ups and downs in the relationship, and it’s a process. That’s what I hope comes out of the book, that that there’s a richness that has to develop in the relationship. It does take time.”

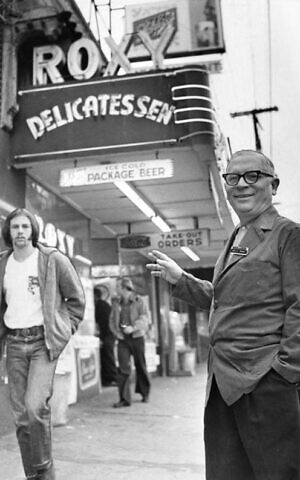

In real life, Marx’s mother and father had a long and successful marriage and raised three children. Her father ran the popular restaurant the Roxy Deli, on 10th and Peachtree Street, which was a popular gathering place for decades.

Writing her book, Marx says, with its title reflecting the Jewish song of gratitude, left her with a greater appreciation for her Sephardic heritage and what her parents managed to pass on to her.

“I value the past and the family I came from and that’s why I wrote the book, to pass all that along so that others are able to appreciate it, too.”

comments