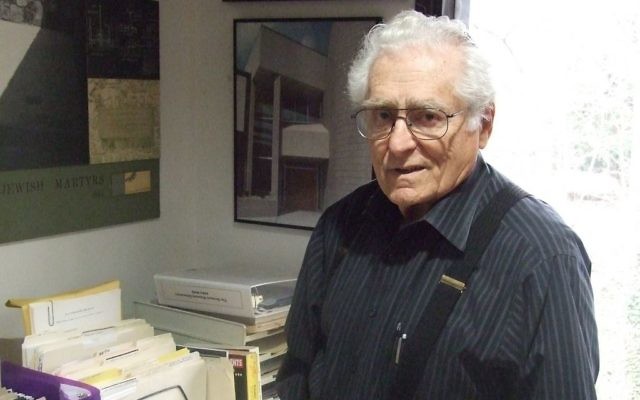

Obituary: Benjamin Hirsch

He escaped Nazi Germany on the Kindertransport, came to Atlanta at age 9, and became an award-winning architect, including the Memorial to the Six Million.

Benjamin Hirsch, 85, who escaped Nazi Germany on the Kindertransport after Kristallnacht and designed the memorial where he and other Atlantans mourned family members lost in the Holocaust, died Sunday, Feb. 11, 2018, three days after falling ill.

“He lived until he died,” Hirsch’s widow, Jacqueline, said in an interview, adding that it was good he didn’t linger because he had suffered enough in life.

That suffering began in his native Frankfurt am Main, Germany. His father was taken during Kristallnacht in 1938, and his mother responded by sending her five oldest children, including 6-year-old Ben, to France on the Kindertransport.

Those five made it to America in 1941, and Ben grew up as an orphan in Atlanta from age 9.

Hirsch’s father died at the Sachsenhausen concentration camp, and his mother and two youngest siblings, Werner and Roselene, who were infants and unable to travel with the other five in 1938, were killed at Auschwitz.

It wasn’t until Hirsch returned to Germany while serving with the U.S. Army during the Korean War that he learned the fate of his little brother and sister from a family friend.

“I stared at him in disbelief,” Hirsch wrote in his first memoir, “Hearing a Different Drummer.” “I had asked him to give me leads to help me find Werner and Roselene, instead he confirmed with an air of certainty that the reports of their death, that I had refused to belief, were true beyond a shadow of a doubt.”

Hirsch’s Army service, the core of “Drummer,” helped him realize that in falling away from Jewish practice in the years after becoming a bar mitzvah, “I was giving up the Judaism that my parents and brother and sister were killed for.”

He became a prominent member of Atlanta’s Orthodox community, serving as the president of Congregation Beth Jacob and Yeshiva Atlanta High School.

His military service also made him eligible for the G.I. Bill, which he used to study architecture at Georgia Tech.

He was about two years into his career when he saw a notice in The Southern Israelite in October 1964 about a meeting to discuss plans for a Holocaust memorial. Hirsch went to the meeting and decided the planned 6-foot-wide, white-marble tombstone was not good enough.

He persuaded the leaders of Eternal-Life Hemshech to do something that not only would serve as a place for survivors to say Kaddish, but also would make a lasting statement to help people remember.

The result, the Memorial to the Six Million, was dedicated at Greenwood Cemetery six months later on Yom HaShoah; Ben’s older brother Jack, a community leader remembered at Jewish National Fund’s annual Yom HaAtzmaut breakfast, was the master of ceremonies.

Costing only $8,500 — $2,000 more than the original tombstone design — the memorial won a national design award in 1968, was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 2008 and remains the site of Jewish Atlanta’s annual Holocaust remembrance ceremony.

“Our hearts are aching with disbelief and sorrow. As president of Eternal-Life Hemshech, I know everyone will miss Ben’s talent, his wisdom, his gentle humor and his commitment to our community,” Karen Lansky Edlin said. “Ben was a giant among men, a dear friend, a treasure and an inspiration to generations of schoolchildren who were touched by his stories of survival and endurance. We are poorer for his loss, but his memory will always be a blessing to everyone who knew and loved him.”

Hirsch told the AJT before the memorial’s 50th anniversary in 2015 that after the dedication, he went home, looked in the mirror and said, “You’re 32 years old. You’ve accomplished everything you wanted. What are you going to do now?”

He had plenty more ahead, including serving as the president of Hemshech, of which he was a founding member. Specializing in religious architecture, his work included the Zaban Chapel at Camp Barney Medintz, an expansion of Beth Jacob, many other synagogues, the Holocaust exhibit at the Breman Museum, and his home on Burton Drive, near Toco Hills and Emory University.

Jacqueline Hirsch said he was the contractor as well as the architect on their house, and in 1966 they moved in, four months and two weeks after construction began.

The couple met at a party at Georgia Tech and married in March 1959. They have four children, Shoshanah Selavan, Adina Hirsch, Michal Apelbaum and Raphael Hirsch; 23 grandchildren; and 19 great-grandchildren.

Hirsch is also survived by his two autobiographies, “Drummer,” published in 2000 after a nearly fatal 1983 car accident inspired him to write about his memories, and the prequel “Home Is Where You Find It,” published in 2006. His third memoir should be published in the spring, his widow said.

“He was a good person, a humble person, an honest person,” who could tolerate anything but injustice, she said. “His life mattered.”

Sign the online guestbook at dresslerjewishfunerals.com. The funeral will be held at 12:30 p.m. Tuesday, Feb. 13, at Crest Lawn Memorial Park. The family requests that memorial donations be made to the Breman Museum, Eternal-Life Hemshech or the Rabbi’s Discretionary Fund at Congregation Beth Jacob. Arrangements by Dressler’s Jewish Funeral Care, 770-451-4999.

comments