Oppenheimer Story Set in Jewish America’s Golden Age

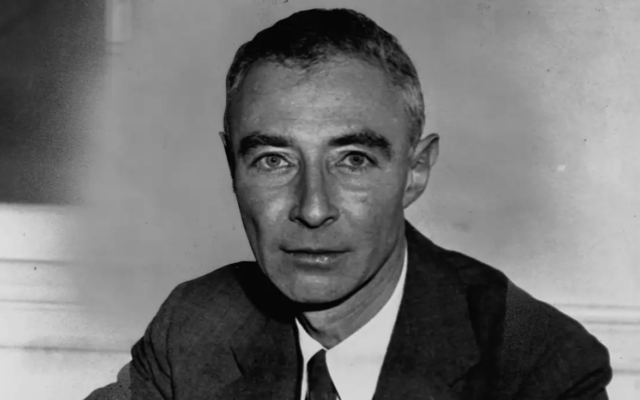

Confrontation between the Jewish J. Robert Oppenheimer and his Jewish adversary, Lewis Strauss, came at a time of unprecedented acceptance of Jews in America.

Christopher Nolan’s epic blockbuster, “Oppenheimer,” which has enjoyed worldwide success is told in a dramatic setting largely populated by characters who are Jewish. Nonetheless, it has been one of the most successful R-rated dramatic films ever in such diverse markets as India, Brazil, France, and Saudi Arabia. In the two months since its release, it’s headed for a total box office of more than $1 billion.

The first two hours of the movie are spent on the absorbing story of how J. Robert Oppenheimer and his brilliant scientific team, many of whom were Jewish, worked together to usher in the Atomic Age.

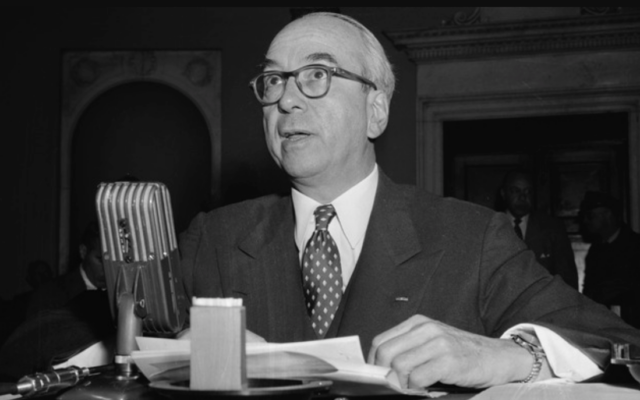

In the last hour of the film, Oppenheimer, who was nominally Jewish, squares off in a losing battle against the chairman of the Atomic Energy Commission, Lewis Strauss, who had also been the president of Temple Emanu-El in New York City for 10 years. In Nolan’s movie, Strauss is the powerful and wealthy Washington insider who is determined to destroy the legendary scientist.

The confrontation of Jew against Jew is set against the background of the so-called Red Scare of the 1950s and concerns over Oppenheimer as a security risk. This fearful period had been largely set in motion by the work of the House Un-American Activities Committee which had investigated left-wing influence in Hollywood, particularly by a number of Jewish screen writers and directors.

Following up on that, there were allegations by Republican Senator Joseph McCarthy that communist operatives had infiltrated the federal government bureaucracy in Washington.

He elaborated on those charges in a series of dramatic Senate hearings that also featured his Senate staffer, Roy Cohn. Finally, there was the conviction of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg for treason, for having passed atomic secrets to the Soviet Union. A Jewish federal judge, Irving Kauffman, who described their crimes as “worse than murder” sentenced them both to death.

According to Emory University professor Eric Goldstein, a noted authority on American Jewish history, the 1950s were a difficult decade for American Jews, who were experiencing unprecedented acceptance in America during the years following World War II. He describes it as “a golden age for American Jewry.”

“There was a huge investment in building new synagogues and Jewish centers, particularly in the suburbs and things like that. And American culture now began to see Jews not as immigrant outsiders or members of some inferior foreign race but as part of the Judeo-Christian tradition where Jews, Protestants, and Catholics all seemed to have a kind of claim to being true Americans.”

But acceptance by American society in the post-war period, according to Goldstein, came at a price. Jews were expected to conform culturally to the values of white, middle-class America. Celebrations of ethnicity and ethnic differences were discouraged. Jews embraced their new identity cautiously.

“Everywhere else in the landscape, they were expected to sort of blend in. So…although America was embracing this idea of a Judeo-Christian tradition…there was an aspect where they were sort of pushed by the society to narrow the definition of what it meant to be Jewish.”

For Oppenheimer, who struggled with his Jewish identity all of his life, the challenge of the new Atomic Age, with its fearsome weapons of mass destruction, demanded that scientists speak out against the development of more powerful hydrogen bombs. It put him on a collision course with Edward Teller, one of Oppenheimer’s émigré Jewish colleagues on the bomb project and ultimately with Strauss, the AEC chairman, who conspired with Cohn and J. Edgar Hoover, the director of the FBI, to demolish Oppenheimer.

Everywhere else in the landscape, they were expected to sort of blend in. So…although America was embracing this idea of a Judeo-Christian tradition…there was an aspect where they were sort of pushed by the society to narrow the definition of what it meant to be Jewish.

For fellow scientists, like Albert Einstein, whose 1939 letter to President Roosevelt urged that America explore the military potential of the atom, Oppenheimer’s decision to fight Strauss and others seemed suicidal. Einstein’s secretary later recalled a meeting Oppenheimer had with Einstein over how to fight back against the attacks in Washington.

Einstein, perhaps mindful of the times, counseled caution, that Oppenheimer faced a losing battle against a political establishment that was arrayed against him. But the nuclear scientist felt he could win and remain an important influence in American government.

Despite Oppenheimer’s courageous stand, his downfall at the hands of Strauss and his allies didn’t set off shock waves in the Jewish community. Like Einstein, many American Jews were sensitive to how far a personal crusade would carry them in American life. Emory University historian Goldstein describes many in the American Jewish community of the 1950s as fearful of eroding their newfound acceptance in American life.

“Most Jews who are trying to achieve this integration into middle class white America were highly, highly aware and sensitive of anything that could possibly mark them as different or dangerous or deviant. They didn’t want anybody to think the Jews were communists or were anything other than good, compliant, conforming, white, middle-class Americans.”

Bob Bahr’s educational series at The Temple, “Oppenheimer, Barbie, Elvis, and Marilyn – Jews, Fame and the Transformation of America,” begins Oct. 19.

- Arts and Culture

- Opinion

- Bob Bahr

- Christopher Nolan

- J. Robert Oppenheimer

- Atomic Age

- Atomic Energy Commission

- Lewis Strauss

- House Un-American Activities Committee

- Joseph McCarthy

- roy cohn

- Julius and Ethel Rosenberg

- Irving Kauffman

- Eric Goldman

- J. Edgar Hoover

- Albert Einstein

- President Roosevelt

- Barbie

- Elvis

- and Marilyn

- Edward Teller

comments