Our Jewish Atlanta Home

The Yiddish word “heimish” means cozy or homey, but it’s also used to express a feeling of welcoming. It’s a word that could be used to describe the Atlanta Jewish community.

The Roots of the Community

In 1968, about 26,000 Jews lived in Georgia. By 2001, this figure had risen to 93,500 and showed no sign of abating, with the overwhelming majority, about 92 percent, of the state’s Jews concentrated in the metropolitan Atlanta area. The Atlanta Jewish community is now estimated at about 135,000.

But the roots of the Jewish community actually can be traced back to Savannah.

Gen. James Oglethorpe settled there in February 1733. Two shiploads of Jews, about 90 people, arrived during the same year and were permitted to stay because of Oglethorpe’s personal influence. This group brought a Torah with them and soon established the colony’s first synagogue, Congregation Mikveh Israel, in 1735. The first settlement failed. By 1741, all but three or four Jewish families had moved north. Most returned during the 1750s, prospered, and reestablished the congregation in 1786. Its first president was Philip Minis. His father, Abraham Minis, probably was the first white male born in Georgia.

There were 400 Jews in the state by 1829; a few families lived in Augusta and isolated areas, while the majority were in Savannah. By 1877, there were Jewish communities of 100 or more persons in seven cities, with congregations in Atlanta; Rome, established in 1871; Athens, 1872; and Albany, 1876. Groups from Eastern Europe began to arrive in the 1880s, settling primarily in Atlanta, Savannah and Brunswick, which had a congregation by 1885. In 1900, there were 6,400 Jews in Georgia.

Organized Jewish communities existed in the early 21st century in 15 Georgia cities, the major ones in Atlanta, 85,900; Savannah, 3,000; Augusta, 1,300; Columbus, 750; Macon, 1,000; and Athens, 600.

The William Breman Jewish Heritage Museum was opened in Atlanta in 1996 and preserves and displays the history of Jews in the state. There is a Hillel at Emory University in Atlanta and at the University of Georgia in Athens, and several Anglo-Jewish newspapers are published in Atlanta, including the Atlanta Jewish Times and The Jewish Georgian. Jewish Studies programs are also found at local universities, with Emory featuring such scholars as David Blumenthal and Deborah Lipstadt.

Source: Jewish Virtual Library: www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/georgia-jewish-history. Encyclopedia Judaica.

How Jewish Atlanta Stands Out

The Yiddish word “heimish” means cozy or homey, but it’s also used to express a feeling of welcoming. It’s a word that could be used to describe the Atlanta Jewish community.

Other words that come up in conversations about the community here are: inclusion, pluralism, cooperation, supportive, unity and yes, unique.

The Atlanta Jewish community is “unlike any other community in the country,” emphatically stated Congregation Etz Chaim Senior Rabbi Dan Dorsch. His words are echoed by The Temple’s Senior Rabbi Peter Berg. “Of all the communities I’ve lived in, the commitment to giving back to the wider community we live in is strongest here,” he said.

Nowhere is this more notable than in the relationship between the Atlanta Jewish community and the Atlanta black community. “This relationship goes back to the Civil Rights movement,” Berg said.

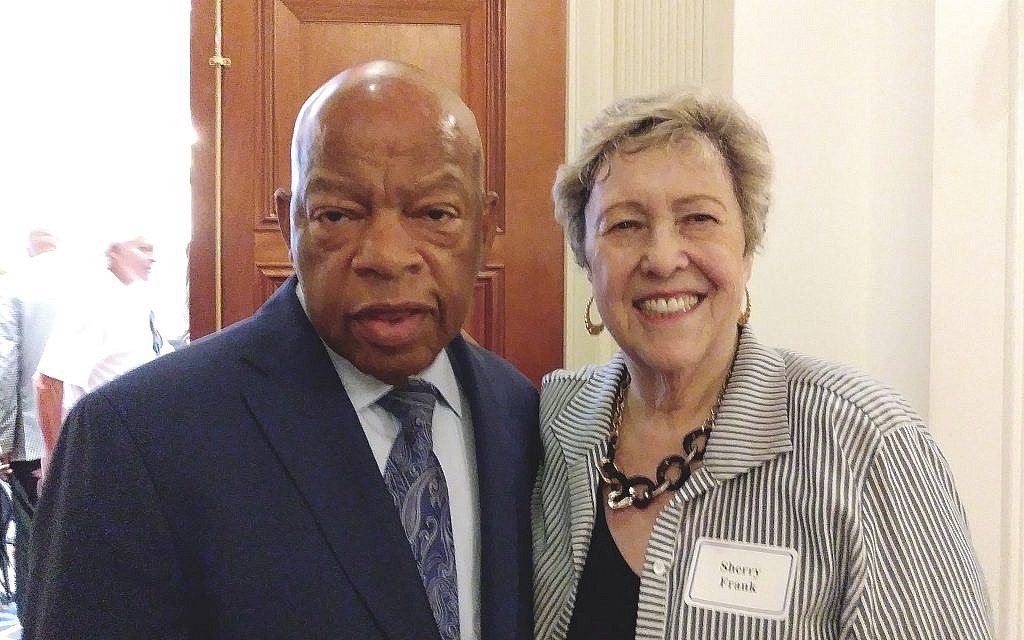

Sherry Frank recalls Atlanta’s motto: “the city too busy to hate.” Even before she was executive director of the Atlanta regional office of the American Jewish Committee and helped establish the Black-Jewish Coalition, Frank recalls the late Jewish architect Cecil Alexander “reaching out to (now Congressman) John Lewis. When African-Americans couldn’t meet in public places, they met in his house,” Frank said.

And when blacks came to Atlanta to participate in the funeral of slain civil rights leader Martin Luther King Jr., they slept in the downtown hotel owned by Jewish community leader Marvin Goldstein.

Frank has long had personal ties with Atlanta black leaders. Her uncle Joe Zimmerman owned a clothing store downtown. “Zimmerman’s was one of the few places where blacks could try on clothes,” she said, adding that “Daddy King” – MLK’s father – preached the eulogy at her uncle’s funeral.

The genesis of the Black-Jewish Coalition was a meeting of 20 Jews and 20 blacks, headed by Alexander and Lewis. “We came together to advocate on behalf of renewing the Voting Rights Act and then decided to continue (after it was renewed),” said Frank, an Atlanta native.

“Generation after generation, people have wanted to build on that history,” she added, underlining the deep relationships that have continued. “John Lewis is like my brother,” said Frank, who just completed writing her memoirs, including stories about these relationships.

To this day, clergy from The Temple and King’s Ebenezer Baptist Church preach in each other’s congregations, to full houses every year.

The internal Jewish clergy relationships are also highly unusual in Atlanta. “It goes back to the generation of rabbis before us,” noted Berg.

Rabbi Dorsch credited The Marcus Foundation for providing financial support to the Atlanta Rabbinic Association. “The rabbinic community, from Reform to [Congregation] Beth Jacob, is close here. We study together. We learn together. It’s very special,” he said, comparing it to his previous pulpit in Livingston, N.J., where the rabbis were highly competitive.

In some cities, says Berg, “The synagogues don’t talk to each other. In Atlanta, there’s a spirit of unity, not of competitiveness.”

A good example of that cooperation is the joint selichot services held by the Conservative synagogues in Atlanta every year, said Margo Dix Gold, immediate past president of the United Synagogue of Conservative Judaism.

“There’s a collegiality in Atlanta and a cooperation that’s really unique,” said Gold, who grew up in Detroit, where the rabbinic relationships are competitive.

“Maybe it’s because we’re in the South, or maybe because so many Atlantans grew up in small communities and they all went to camp together.”

Atlanta is special, however, not just for the cooperation between the 40-plus Jewish synagogues, the extraordinary relationships between the city’s Jewish and black populations and the large number of regional offices of the AJC, the Anti-Defamation League and the American Israel Public Affairs Committee – not to mention the Israeli Consulate. Gold points to the unusually close relationships in the interfaith world.

She remembers when retired minister Wayne Smith received a grant from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation to bring together representatives from the interfaith world, “people who had outreach capacity,” among them Gold. “It was one-third Jews, one-third Muslims and one-third Christians, and we went to Turkey for 10 days in 2002. We sat with a different person on the bus each day and swapped roommates. It was about getting to know each other, and we wrote principles of being respectful, listening and understanding. When we came back from that trip, interfaith relations were never the same.”

But Gold believes that the Atlanta Jewish community stands out in other ways as well. “There’s a legacy of philanthropy and giving of service. In our community, there are a strong number of families who support the community financially and by being in the room and rolling up their sleeves.”

Berg said the community “stands on the shoulders of the people before us, with (the late) Erwin Zaban chief among them.” Certainly Zaban, who contributed the land in the name of his parents for the building of the Marcus Jewish Community Center of Atlanta, was among the most notable of his generation. But that sense of responsibility to the community didn’t end with his generation. Nor did it end with his, and his daughters’ leadership at the Jewish Federation of Greater Atlanta.

Nearly two years ago, the Jewish Federation launched a program, known as The Front Porch, to better serve the Jewish community. Among the many changes initiated by the Federation is its method of allocating the funds that it raises. Chief Impact Officer Jodi Mansbach now oversees grantmaking, which used to be called allocations.

Today the Atlanta Jewish community “is known throughout the country in the amount of support it gives for any Jewish camper,” Mansbach said. The Jewish Federation is also known for providing extensive grants for teen education and involvement. “There’s a recognition that the experience Jews have as teens is important for remaining Jews. We are funding programs that are already working with teens and helping them work better.”

One of those teen programs supported by the Jewish Federation is the Jewish Kids Group, which was established in 2012 by founder and executive director Ana Robbins. Providing both an after-school program and a Sunday School program, JKG now serves more than 300 students in five sites around Atlanta. Robbins plans to open two more after-school programs and seeks to serve 450 students.

As she notes, independent after-school programs such as JKG is “a nascent and emerging field” in the country. “Atlanta is a highly innovative city that supports young entrepreneurs,” she said, providing examples of that support.

Early fellowships given to JKG and the Atlanta Jewish Music Festival “provided us with a hechsher [kosher designation] and made it so I could raise money from the community,” Robbins recalled. “We were also allowed to have a mailbox at the Federation, which gave us needed credibility.”

JKG is just one of the distinct programs that have raised the national profile of the Atlanta Jewish community. There’s also In the City Camp, SOJOURN (Southern Jewish Resource Network for Gender and Sexual Diversity), JScreen genetic testing, and JumpSpark teen programming. Pre-existing Jewish organizations around the country have also been flocking to the Atlanta area, including Moishe House residential program for young adults, OneTable Shabbat dinners, Honeymoon Israel couples’ trips, and, the latest, Repair the World volunteer program.

These groups join other organizations that have long made the Atlanta Jewish community stand out, such as the MJCCA’s Book Festival, and the Atlanta Jewish Film Festival, both among the largest in the country.

According to Mansbach, Atlanta has transitioned “from a community where everyone knew each other to a community with the highest mobility rate, where we don’t know each other.” Strong leaders help to unite the dispersed community, she said.

For Rabbi Berg, “it’s meaningful to be a part of a community that wants to work together.”

- Community

- Jan Jaben-Eilon

- congregation etz chaim

- The Temple

- Rabbi Peter Berg

- Sherry Frank

- Beth Jacob

- Anti-Defamation League

- AIPAC

- jewish federation of greater atlanta

- Atlanta Jewish Music Festival

- Atlanta Jewish Film Festival

- MJCCA’s Book Festival

- In the City Camp

- SOJOURN

- jscreen

- JumpSpark

- Moishe House

- OneTable

- Honeymoon Israel

- Repair the World volunteer program.

- home and garden

- The Jewish Georgian

- David Blumenthal

- Deborah Lipstadt

- jewish atlanta

- Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

- Black-Jewish Relations

- Civil Rights Movement

- John Lewis

- The Marcus Foundation

- Front Porch

- jewish kids group

- Margo Gold

- Rabbi Daniel Dorsch

- Ana Robbins

- Jodi Mansbach

- Interfaith Relations

- Rabbi Jacob M. Rothschild

- The William Breman Jewish Heritage Museum

comments