Our Neighbors’ Affliction is Our Affliction

On the eve of Pesach 1981, AJT wrote: “the Jewish community and the city as a whole are faced with another affliction - the tragedy of the dead and missing children."

Dave Schechter is a veteran journalist whose career includes writing and producing reports from Israel and elsewhere in the Middle East.

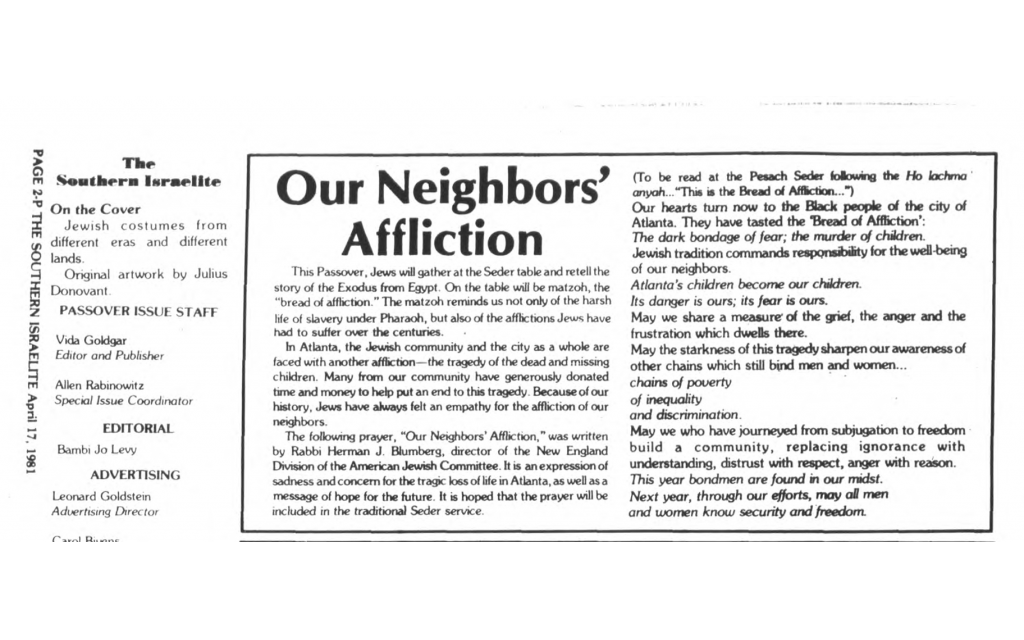

On the eve of Passover in 1981, The Southern Israelite published a message headlined “Our Neighbors’ Affliction.”

Atlanta’s weekly Jewish newspaper told its readers: “The matzoh reminds us not only of the harsh life of slavery under Pharaoh, but also of the afflictions Jews have had to suffer over the centuries,” and then turned its attention to the present.

“In Atlanta, the Jewish community and the city as a whole are faced with another affliction – the tragedy of the dead and missing children. Many from our community have generously donated time and money to help put an end to this tragedy. Because of our history, Jews have always felt an empathy for the affliction of our neighbors,” The Southern Israelite (renamed the Atlanta Jewish Times in 1987) said.

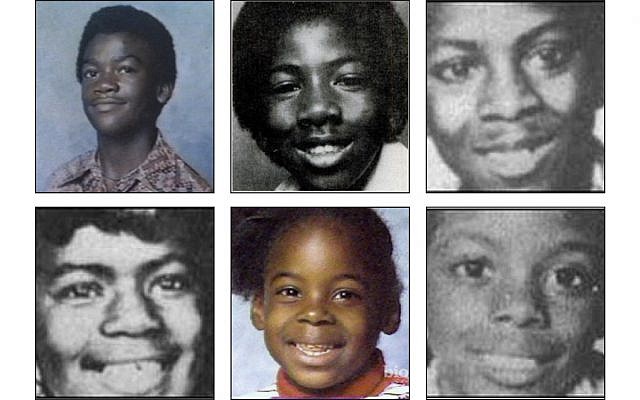

Between July 1979 and May 1981, at least 29 black children, adolescents and young adults were killed, most by strangulation or asphyxiation.

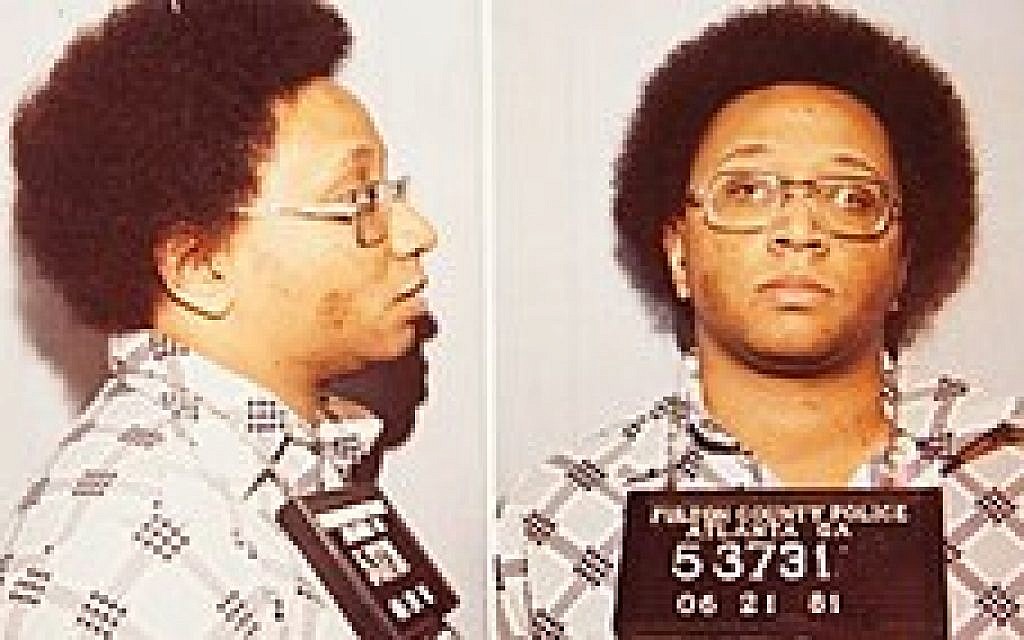

Police arrested 23-year-old Wayne Williams, who was convicted in the murder of two adults, and suspected by police in the child killings. Now 60 years old and still protesting his innocence, Williams is serving consecutive life sentences in prison.

The announcement by Atlanta Mayor Keisha Lance Bottoms that authorities will re-examine evidence (as opposed to re-opening the cases ) prompted a look back at the Jewish community’s response to that tragedy.

“Our Neighbors’ Affliction,” was the title of a prayer written by Rabbi Herman J. Blumberg, director of the AJC’s New England division. That prayer included the following lines:

Our hearts turn now to the Black people of the city of Atlanta. They have tasted the ‘Bread of Affliction’:

The dark bondage of fear; the murder of children.

Jewish tradition commands responsibility for the well-being of our neighbors.

Atlanta’s children become our children.

Its danger is ours; its fear is ours.

May we share a measure of the grief, the anger and the frustration which dwells there.

A reading of The Southern Israelite and other sources from that period suggests that while the Jewish community felt empathy and involved itself at various points, for the most part it had other concerns.

By the late 1970s, Atlanta’s Jewish population, which had stagnated for several decades after the 1915 lynching of Leo Frank, was approaching 27,500 and expanding geographically. New congregations were forming in Gwinnett and Cobb counties and a new Jewish Community Center opened beyond Interstate 285.

There was concern about black-Jewish relations fraying after the mid-1960s American civil rights movement and the June 1967 Six-Day War in Israel. Atlantan Andrew Young resigned as U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations after the State Dept. was misled about his meeting with an official of the Palestine Liberation Organization. Southern Christian Leadership Conference Co-founder Rev. Joseph Lowery, of Atlanta, sang “We Shall Overcome” with PLO leader Yasser Arafat in Lebanon. Rev. Hosea Williams, another Atlantan, presented a Martin Luther King Jr. “peace award” award to Libya’s leader, Col. Muammar Qaddafi.

The Southern Israelite on Oct. 19, 1979, published an in-depth look at Jewish-black relations in Atlanta. The article concluded with a quote Gerald Cohen, Atlanta Jewish Federation’s vice president for community relations, had delivered to a meeting of Jewish federations from throughout North America: ‘It is the obligation of each Jew in his ordinary pursuits to establish contacts to dispel tensions and fears. It must be done at all levels. We all know the story. We all share the burden.’”

As Southeast regional director of the American Jewish Committee, William Gralnick shouldered that burden. Gralnick had a reputation for building bridges across racial and ethnic lines, and as an expert on the Ku Klux Klan.

Fifteen children between the ages of 7 and 14 already had disappeared and been found dead when a boiler exploded at the Bowen Homes daycare center on Oct. 13, 1980, killing four children and an adult. “We were inches from a race riot because of the instant assumption it was connected” to the child killings, Gralnick recalled. “That’s how tense the city was.”

That tension followed him home. “One night my wife and I were going out. We had retained a baby sitter. My oldest son, who was of Montessori age, stood at the screen door crying, ‘Is the bad man going to come to get me while you’re out?’ Nothing any parent wants to deal with,” said Gralnick.

A front-page headline in The Southern Israelite on Oct. 24, 1980, declared: “Jewish community rallies to aid in search for missing children.” This appears to have been the newspaper’s first mention of the story, 14 months after the first death.

“Although a number of Jewish individuals have been involved in helping search” for missing black children, a greater effort was urged by Max Rittenbaum, president of the Atlanta Jewish Federation. “Our compassion and sympathies go to to the families of these children and we are determined to help get to the bottom of this tragedy,” Rittenbaum said.

Jewish youth groups “all expressed a desire and willingness to cooperate in aiding families and children to prevent any further crimes and in searching for any leads to solve these mysterious disappearances,” Community Relations Council Chairman Larry Bogart said.

Rabbi Alvin Sugarman urged congregants at The Temple “to participate in the reward fund, and talk to their friends in the black community to let them know that they did care and we are one community.”

An editorial in that edition began, “No parent—indeed, no decent human being—can fail to be affected by tragic events which have rocked the Atlanta community.”

“The dead and missing all happen to be black. For too long, these deaths and disappearances seem to have been treated as a ‘black tragedy,’ . . . or an ‘Atlanta problem.’ No longer. Tragedy does to recognize color differences. Nor does it stop at municipal boundaries,” read the editorial, likely written by editor and publisher Vida Goldgar.

In February 1981, as the death toll passed 20, about 30 members of the local Israeli community participated in the search for missing children. Organized by Israel’s Consul General in Atlanta Joel Arnon, they included consular staff, schlichim (emissaries) posted in Atlanta, Israeli professors and students. “We feel strongly that the Israeli community should help the city of Atlanta in this tragic time,” a consulate spokesman told The Southern Israelite.

The number of missing and murdered had reached 22 when the American Jewish Committee’s Interreligious Affairs Commission met in Atlanta on March 9. A memorial service was led by Rabbi Marc H. Tanenbaum, AJC’s national inter-religious director, and Rabbi Judah Mintz of Congregation B’nai Torah, president of the Atlanta Rabbinical Association.

Gralnick told the Atlanta Constitution, “This is the same prayer [Kaddish] that Jews say for their own departed, and it is the same prayer that is said every year on behalf of the Holocaust victims.”

Two days earlier, on a Saturday, Tanenbaum addressed the Christian Council of Metropolitan Atlanta. Tanenbaum’s intention to attend such an event on Shabbat upset Rabbis Emanuel Feldman at Congregation Beth Jacob and Marc Wilson at Congregation Shearith Israel, both of whom sent him critical letters beforehand.

Tanenbaum replied to Feldman that he had “wrestled with my conscience.” The organizers “pleaded with me to find a way to come that would not violate my religious principles, since they felt that the problems of black-Jewish relations and the anguished atmosphere in Atlanta over the murder of 18 black children required a message of healing which they felt I could bring.”

At the time, Sherry Frank was associate director of the AJC’s Atlanta office, having come aboard in September 1980. (She became director in July 1981 when Gralnick became director of the AJC’s Miami office.)

“I remember it so vividly,” Frank said. When he spoke to the Christian Council, “Marc said that for a Jewish community that saw our babies thrown up in the air and shot like pigeons in the Holocaust, is there any doubt that we are with you today, feeling your pain?”

Rumor-mongering became such a problem that on May 1, The Southern Israelite – along with the Anti-Defamation League and the Atlanta Urban League – sponsored an advertisement cautioning against spreading information without determining its accuracy.

The B’nai B’rith Achim Lodge planted a tree in Israel as a memorial to the slain children. The Southern Israelite’s May 8 edition published a photograph of Barry Dreayer, president of the B’nai B’rith Achim Lodge, and Andrew Adler, vice president, presenting aides to Atlanta Mayor Maynard Jackson with a symbol of that tree.

The last disappearance was on May 22, 1981. Williams was arrested soon after.

In the summer that followed, the Jewish community continued its outreach. In one effort the Union of American Hebrew Organizations and the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People sponsored a week’s vacation in August at the Reform movement’s Camp Coleman in Cleveland, Ga., for some 250 black children.

In its 1981 pre-Passover edition, an editorial in The Southern Israelite noted that children are very much a part of Passover and Easter.

“Yet, who of us can watch the happy faces of our children without a thought of the Atlanta families whose children have been tragically taken from them. As we gather in observance of our holiday, let our hearts reach out in prayer to those whose loss is so great.”

A jury found Wayne Williams guilty of murdering:

Nathaniel Cater, 28

Jimmy Ray Payne, 21

Police attributed these deaths to Williams (closed cases):

Alfred Evans, 13

Yusef Bell, 9

Eric Middlebrooks, 14

Christopher Richardson, 12

Aaron Wyche, 10

Anthony Carter, 9

Earl Terrell, 11

Clifford Jones, 13

Charles Stephens, 12

Aaron Jackson, 9

Patrick Rogers, 16

Lubie Geter, 14

Terry Pue, 15

Patrick Baltazar, 11

Curtis Walker, 13

Jo Jo Bell, 15

Timothy Hill, 13

Eddie Duncan, 21

Larry Rogers, 20

Michael McIntosh, 23

John Porter, 28

William Barrett, 17

These cases remain open:

Edward Smith, 14

Milton Harvey, 14

Jefferey Mathis, 10

Missing person whose body was never found:

Darron Glass, 10

Deaths were initially part of the official investigation, but police found insufficient evidence to link to a serial killer or anyone else:

Angel Lanier, 12

LaTonya Wilson, 7

CNN Source: Homicide Task Force

- Dave Schechter

- Reflections

- The Southern Israelite

- Wayne Williams

- Mayor Keisha Lance Bottoms

- Rabbi Herman J. Blumberg

- Max Rittenbaum

- Atlanta Jewish Federation

- Rabbi Marc H. Tanenbaum

- Rabbi Judah Mintz

- Congregation B'nai Torah

- Atlanta Rabbinical Association

- The Temple

- News

- Community

- Rabbi Alvin Sugarman

- Sherry Frank

- William Gralnick

- atlanta serial killer

- American Jewish Committee

- Black-Jewish Relations

- Interreligious Affairs Commission

- Barbara Asher

comments