Public Television Examines ‘The U.S. and the Holocaust’

The new documentary weighs America's response to the Nazi genocide.

Dave Schechter is a veteran journalist whose career includes writing and producing reports from Israel and elsewhere in the Middle East.

Eighty years after two-thirds of Europe’s Jewish population was murdered in the Nazis’ “Final Solution,” the questions persist.

What did the United States government — and the American public — know and when did it know it? Why did the U.S. not do more to save Jewish lives? What more could or should have been done?

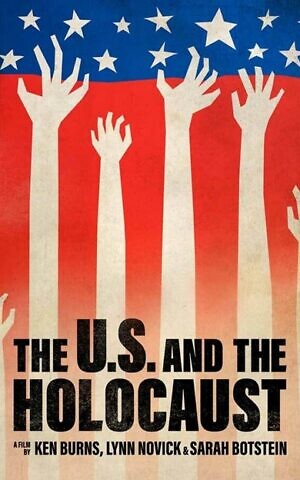

“The U.S. and the Holocaust,” a three-part documentary airing Sept. 18-20 on PBS stations, considers these issues as it explores the attempted extermination of a people because they were Jewish — killing on a scale so vast that a new word was created to define it: genocide.

The program was co-directed and co-produced by Ken Burns, Lynn Novick and Sarah Botstein, filmmakers known for work that is rich in detail and expansive in perspective. Peter Coyote’s familiar voice narrates Geoffrey C. Ward’s meticulous script.

Though “The U.S. and the Holocaust” marks Botstein’s directorial debut, she has produced numerous documentaries with Burns and Novick. “We try to make our films for a general audience,” Botstein told the AJT, adding that “a lot of people who think they know a lot about this subject may be surprised at the things they learn.”

Asked what surprised her, Novick responded: “I came into this with an overly simplistic idea, that the reason why America did not do more to help refugees and try to save people was because we didn’t know, and the record will show that Americans knew quite a lot.”

Novick, who was raised by Jewish parents “in a completely secular environment,” said that she maintains “a very strong Jewish identity and a very strong sense of a connection to the culture and to the history.”

The project grew out of conversations with the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum about a documentary that would dovetail with its “Americans and the Holocaust” exhibit, which includes a look at what U.S. newspapers reported during that time period.

The documentary draws from archival film, photographs and documents, using camera techniques sometimes referred to as the “Ken Burns Effect.”

Historian interviews provide context and, as with Deborah Lipstadt, blunt assessments. “There is much we can be proud of, of this country, but the episode of America in the Holocaust is not one that redounds to our credit,” she says in the documentary.

Since her interview, Lipstadt has become the U.S. Special Envoy to Monitor and Combat Antisemitism and is on leave from Emory University.

The documentary also features Jewish Americans who discuss with undisguised emotion how the Holocaust impacted their families. Daniel Mendelsohn, the author of “The Lost: A Search for 6 Million,” chokes up as he talks about the letter his grandfather received after the war, informing him of family who had perished, a multi-generational trauma.

Off-camera voices read from letters, speeches and the diary of perhaps the only Holocaust victim whose name is known globally, Anne Frank.

The saga of the Frank family — Otto and Edith, and their daughters, Annelies Marie and older sister Margot — intersects with that of the Geiringer family, who lived near the Franks in Amsterdam and, likewise, were in hiding when captured by the Gestapo and sent to concentration camps. Eva Geiringer (Schloss), now 93, gives a graphic account of surviving Auschwitz. She describes the Anne Frank she knew and how shared grief linked the two families.

The tone and language of today’s immigration debate resounds from a century earlier. “The United States was drawing her skirts about her in fear, lest she be contaminated by the alien. The temper of the Congress, I discovered, is the temper of the people,” says an off-camera voice, quoting the late Emanuel Celler, who represented a New York City congressional district for 50 years and argued for the admission of Jewish refugees. One fold in those skirts was the Johnson-Reed Act of 1924, an immigration law that set national quotas and, in turn, reduced opportunities for those fleeing Nazi terror.

Yes, the U.S. admitted some 225,000 refugees, more than any other nation. “But during the years when escape was still possible, the American people and their government proved unwilling to welcome more than a fraction of the hundreds of thousands of desperate people seeking refuge,” the narration explains.

The history lesson covers lingering post-World War I resentments that allowed an undistinguished corporal to seize power in what was considered one of the most cultured nations in Europe. Adolf Hitler was aware of U.S. immigration laws and how Native American and Black citizens were treated in this country. Nazi Germany found pockets of sympathy and support in America, most notably from the celebrated flyer Charles Lindbergh.

“Americans cannot grasp the scope and the scale of the crime,” historian Daniel Greene says. Indeed, the numbers can be overwhelming — how many Jews were killed where, when and by what means; the numbers of refugees; the numbers forced into ghettos; the numbers who received visas and the numbers who did not; the number of Jews in Europe prior to the Holocaust, and the fraction that remained after.

The obvious villains are Hitler and the Nazi henchmen who planned the “Final Solution” to the so-called Jewish Question and the troops and local collaborators who carried out the arrests, deportations and killings.

The heroes, who would have rejected that label, were diplomats and consular officers who struggled with obstruction and antisemitism from the State Department, private individuals and non-governmental organizations that succeeded in saving lives and the Jews and non-Jews who risked their lives to smuggle out information to a disbelieving world.

President Franklin Delano Roosevelt is portrayed as neither villain nor hero. Sympathetic as he might have been, Roosevelt needed the support of powerful southern Democrats to advance his New Deal agenda — politicians who opposed relaxing immigration quotas. A Depression-weary populace had little appetite for increased immigration, fearing the loss of jobs and, after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, fearing infiltration by spies from the Axis nations.

“We’re committed to punishing the perpetrators,” Greene says. “We do rally as a nation to defeat fascism. We just don’t rally as a nation to rescue the victims of fascism.”

Roosevelt could not afford to be seen as taking actions directly benefiting Jews, particularly the diversion of military resources. Debate continues today over whether rail lines that led to the concentration camps should have been bombed.

“I think they should have,” Lipstadt says. “Not because it would have rescued a major portion of the 6 million, but as a statement, as a message to the Germans: ‘We know what you are doing. We cannot abide what you are doing. This is our response to what you are doing.’ Yes, they could have done that.”

Historian Rebecca Erbelding says: “I don’t think there’s a right answer, because I don’t think there’s a way in which we look back and think that we did the right thing. … No matter what we did, I think we look back and wonder what would have happened had we done the other thing.”

The documentary also addresses divisions within the Jewish community, between communal leaders who favored a low-key effort to influence Roosevelt and others who favored a louder, more public approach.

The documentary was in production when the Anne Frank House in Amsterdam and the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum determined that Otto Frank’s visa application had not been denied but, rather, had fallen victim to “bureaucracy, war and time.” This news was worked into the story.

Anne and Margot Frank died of typhus at Bergen-Belsen in February 1945, a couple of months before that camp was liberated. After the war, Anne’s diary was returned to her father, who had survived Auschwitz, and became a worldwide sensation when published in 1947. Lipstadt sees the theater and film adaptations as presenting a tale of triumph, not tragedy. “It’s a wonderful story. … But it’s not the story of the Holocaust, not the story of the Shoah, not the story of the genocide,” she says.

The diary’s most quoted passage — “I still believe, in spite of everything, that people are truly good at heart” — was written on July 15, 1944, just 20 days before the family’s capture. Geiringer says of Anne Frank: “If she would have survived, she would not have said that, I think.”

Raphael Lemkin was a Jewish refugee from Poland, who lost 49 members of his family. The legal scholar combined “genos,” an ancient Greek word for race or tribe, and “cide,” from the Latin word for killing, to form “genocide,” for the first time putting a name to the Nazi murders of an estimated 6 million Jews and 5 million others.

Benjamin Ferenz, now 102-years-old, explains in the documentary why he deliberately included this new word in his arguments as a prosecutor in one of the postwar trials of Nazi leaders.

“Ken says, ‘History rhymes or you find echoes or you see patterns or you see things that were important about the past and inform how you view the present,’” Botstein said, channeling Burns.

“The U.S. and the Holocaust” considers how the past informs the present, allowing viewers to determine for themselves whether aspects of the years 1933-45 remain with us eight decades later.

- News

- Arts and Culture

- Dave Schechter

- GPB

- PBS

- public broadcasting

- Georgia Public Broadcasting

- nazis

- holocaust

- WWII

- genocide

- Ken Burns

- Lynn Novick

- Sarah Botstein

- Peter Coyote

- Geoffrey C. Ward

- Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society

- warsaw

- Lodz

- U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum

- Ken Burns Effect.

- Deborah Lipstadt

- U.S. Special Envoy to Monitor and Combat Antisemitism

- Emory University

- Daniel Mendelsohn

- The Lost: A Search for 6 Million

- Anne Frank

- Gestapo

- Auschwitz

- Emanuel Celler

- Johnson-Reed Act of 1924

- Adolf Hitler

- Charles Lindbergh

- Daniel Greene

- President Franklin Delano Roosevelt

- Rebecca Erbelding

- Anne Frank House

- Bergen-Belsen

- Raphael Lemkin

- Benjamin Ferenz

comments