The 100-Year Pandemic

The AJT looks back nearly a century to the last major pandemic in 1918 comparing it to our currently one and how it affected the Jewish community.

Herbert Taylor was 23 when a dangerous flu spread through soldier ranks during World War I, nearly a century ago, and wiped out thousands a day. The Southern Jewish Archives of the William Breman Jewish Heritage Museum records the history of the 92-year-old Atlanta native, recalling his service during the war and his encounter with what became a global pandemic.

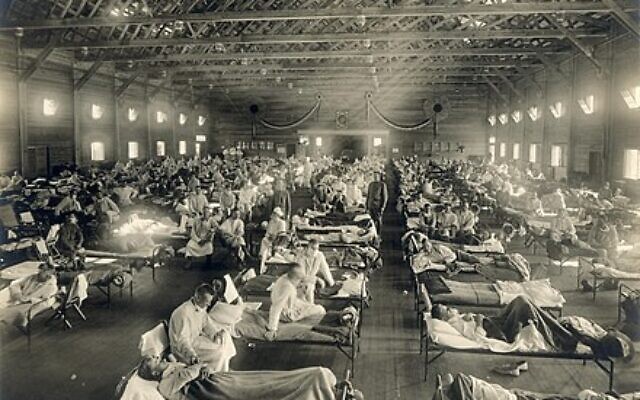

Taylor was training at Camp McLellan in Alabama and was supposed to head to Camp Dix in New Jersey when the “flu” broke out. “We lost 2,000 men a day to the flu. When the flu was over, we didn’t have enough men left … So they sent us back to Camp Gordon” in Atlanta, according to an interview conducted in 1987 through the Cuba Family Archives.

The history captured by the Atlanta museum, along with national Jewish organizations and public health records, bears an uncanny resemblance to what the Jewish community and the world is experiencing today. It helps to put our present global health crisis in perspective to read about the pandemic that occurred soon after the turn of the 20th century.

In a footnote of the transcript from the Taylor interview, the flu of that time was further defined as the 1918/1919 flu pandemic or the Spanish flu.

“In the U.S. it first appeared in a military camp in Kansas. Ironically the close concentration of large numbers of soldiers in training camps for World War I hastened the pandemic and increased the transmission of it. It returned in a second wave in 1918, which proved even deadlier than the first.”

The pandemic raged from January 1918 to December 1920, according to the transcript footnote. “It was one of the deadliest natural disasters in human history. Ultimately it infected 500 million people worldwide, of which some 50 million … died. It was especially fatal to young adults,” according to the transcript footnotes.

Those figures are a far cry from the latest figures from 2020, showing nearly 43.5 million cases of COVID-19 have been reported worldwide and 1.2 million deaths. Still, some of the reports from 1918 are eerily familiar to what is occurring in 2020.

From the archives of the JDC (Joint Distribution Committee), a Jewish relief agency, we learn that fundraising had to be suspended due to the restrictions of the health care authorities concerning “an unusually deadly influenza pandemic that affected JDC operations domestically and overseas as well.”

On Oct. 8, 1918, JDC admitted that on account of “the epidemic of Spanish Influenza . . . it would be impossible to get together the crowd at the meeting scheduled in New York.”

On Dec. 11, 1918, Harry Plous, a member of the Upper Peninsula Organizing Committee, informed JDC’s Secretary Albert Lucas, “We are getting ready for that great relief campaign, but on account of the Spanish Influenza, we are going to make a big stop in this work. It is not allowed to hold, not only mass meetings but not even four persons can assemble.”

Elsewhere around the country in 1918, the Spanish flu was also wreaking havoc in the Jewish community.

The National Institutes of Health reported in a 2010 article entitled, “Immigration, Ethnicity, and the Pandemic,” that the “Spanish influenza epidemic of 1918” was arousing fears of anti-Semitism within the Jewish immigrant community.

“History had taught Jewish spokespeople that they must at all costs deflect blame for the pandemic away from Jewish immigrants less they trigger the sort of medicalized anti-Semitism they had left Eastern Europe to escape,” Alan Kraut, who had a doctorate from the American University history department, wrote in the NIH report. “At the same time, the health and safety of the people had to be protected by discussing disease prevention in every available public forum. In Denver, public health officers praised the Jewish community for its compliance.”

That praise came despite the high cost of medical care at the time. “Although physicians held a place of great admiration and respect among Eastern European Jews, physician care was a luxury that few could afford,” according to Kraut’s reporting.

What would happen in communities with higher concentrations of Eastern European Jewish immigrants?

In the fall of 1918, a primary task of the 20-year-old Jewish Daily Forward newspaper, New York’s Yiddish-language daily also known as Forverts, was to explain the illness to the Jewish immigrant community and why cases must be reported. Kraut wrote, “The paper warned, ‘Influenza is often the prelude to pneumonia, which ends very often with death.’ Noting that previously flu need not be reported, the article emphasized, ‘The Health Commissioner has ordered that from now on, doctors should report on every case of influenza and pneumonia, exactly as they do for [other] contagious illnesses.’ Likewise, the Forward kept its readers apprised of the epidemic’s spread.”

On Sept. 21, the Forward “informed readers that 47 new cases had been reported to the New York Board of Health, but that the Commissioner had been reassuring nevertheless and explained that meetings were being held to prevent the flu’s transmission. Meanwhile, the Forward advised readers to ‘be cautious; if anyone should sneeze, he should not sneeze into someone’s face, but into a handkerchief.’ Such advice did not consider the obvious. For impoverished immigrants, many from rural villages, standards of etiquette and urban hygiene were still lessons to be learned. Not everyone owned a handkerchief.”

Cases continued to mount and almost every issue of the Forward included new rules on flu prevention, Kraut wrote. The paper “advised readers to not use hand towels in public places and not to drink from cups that others had used. Knowing the popularity of candy stores and soda fountains in immigrant neighborhoods, Yiddish-speaking Jews were reminded, ‘Above all you should in particular be careful in ice-cream soda places: do not drink if the glass has not been completely and appropriately cleaned.’ There were warnings against public spitting and using ‘any napkins, handkerchiefs, clothes or bedding that an ill person has used.’ In a community where many smoked, pipe smokers were reminded, ‘Do not smoke from a pipe that has been in another’s mouth.’ While few Jewish immigrant households in this era had their own telephones, many used public phones and were reminded, ‘When you speak on the telephone, keep your mouth farther from the receiver.’

“These were familiar words of advice, not unlike reminders designed to avoid transmission of tuberculosis, the bane of impoverished immigrants. Children were of special concern and readers were cautioned, ‘Do not let your child play with things that belong to other children.’”

In October 1918, all stores except food stores were ordered to close no later than 4 p.m., Kraut’s NIH report continued. The Board of Health ordered that landlords were legally required to provide heat to tenants by Nov. 1. “Each home in the city must now be heated. It is a danger for people who are recovering from influenza and pneumonia to be in cold houses. Cold residences also encourage the development of the sickness,” the order stated, as reported by Kraut.

While the Forward was skeptical of the government response to the pandemic, the Jewish community, known for being self-sufficient, particularly in the face of anti-Semitism, mobilized to help their own, according to Kraut.

“At the time of the influenza epidemic, New York’s Jewish community had formed a kehillah, a communal organization to govern itself. … Although it only lasted from 1908 to 1922, the New York Kehillah published the names of 65 Jewish organizations in New York where help and information were available during the influenza epidemic. One such organization, the Workmen’s Circle or Arbeiter Ring, offered medical assistance to its members and their families.

“Funerals were an equally important matter. Observant Jews must be buried in sacred ground separate from non-Jews. In the fall of 1918, the Workmen’s Circle appointed its first funeral director to watch over the growing number of funerals of flu-stricken members in the Greater New York area wanting to be buried in Workmen Circle cemeteries. During the height of the epidemic, there were 14 to 16 funerals a day among Circle members, an unprecedented daily toll.

“Religious organizations in the immigrant communities also sought to protect their communities. Many churches agreed to remain closed during the epidemic or increased the number of masses to spread out the congregation and prevent opportunities for infection. In the Jewish community, the head of the rabbinic court or Beis Din of New York announced that Jews in mourning who must sit shiva ‘can and must be lenient with regard to the laws of mourning.’ Mourners were required by Jewish law to stay at home, do no work or domestic tasks, or even change clothes or bathe. However, because of the flu, mourners were told, ‘He who lives in narrow rooms or such a one who must have fresh air may go around outside for a few hours each day on account of health.’ The bereaved were told they could buy food and need not go barefoot, ‘even at home, but wear shoes in order not to catch a cold. God forbid.’”

Towards the end of the pandemic, in October 1920, JDC medical advisor Dr. Harry Plotz prepared a report about his trip to Eastern Europe in which he visited and inspected health conditions of cities, orphanages, schools and refuge camps in Poland, Lithuania and Ukraine. “The presence of an epidemic in one region is a menace to the world, as the influenza epidemic has already taught us,” Plotz wrote in a letter recorded in the JDC Archives. He was speaking specifically about the control and eradication of typhus fever, which he believed “would be accomplished by worldwide cooperation, a plan which I hardly think feasible at this time.”

If today’s health battles seem daunting, consider that back some 100 years ago, the “Spanish influenza” was just one of a string of maladies afflicting the globe.

For instance, a report of the activities of the American Zionist Medical Unit between 1918 and 1920, significantly subsidized by JDC, presented a desperate situation in Palestine, according to its archives.

“Shortly after arrival of the Unit in Palestine a cholera epidemic broke out in Tiberias,” the report to the JDC stated. “The military authorities took hold of the situation energetically … There were at the time about 7,500 people in Tiberias, 4,000 resident Jews, 1,100 Jewish refugees from Jaffe, 2,000 Muslims and 3,000 Christians. To meet the needs of this population afflicted with endemic meningitis, Spanish influenza, malaria, dysentery and other gastro-intestinal disturbances, and the usual eye diseases, a polyclinic was opened.”

And we think we have a massive global health crisis today.

comments