The Instrument of the High Holidays

Rabbi Dr. Natan Slifkin discusses the historical significance of the shofar during the High Holiday season.

For Jews around the world, the soul-piercing sound of the shofar is charged with religious significance, evoking a perennial yearning for deliverance and renewal.

The sound of a shofar emanated from Mount Sinai. It heralded the new moon and the jubilee year. Shofars were used in battle and in the Temple orchestra. Rosh Hashanah, the start of the Jewish new year, is described in the Bible as “a day of blowing” the shofar, and its sounding at the conclusion of Yom Kippur service marks the end of the fast.

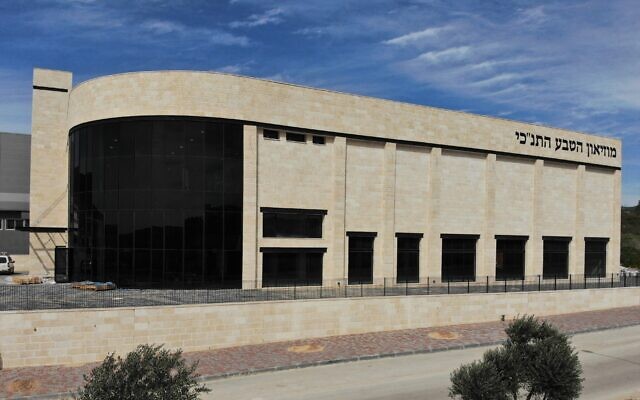

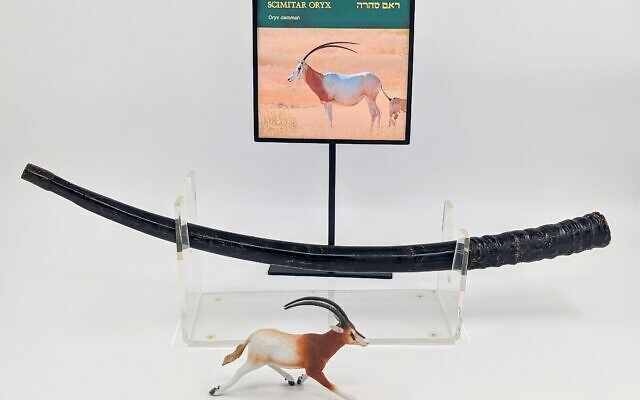

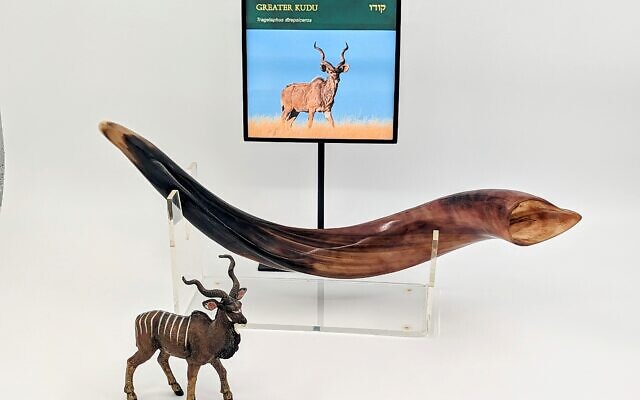

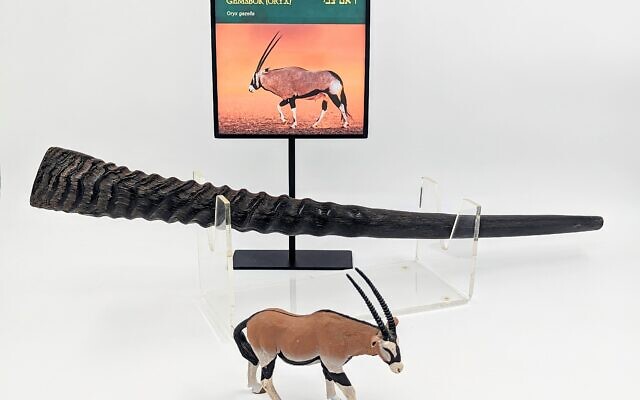

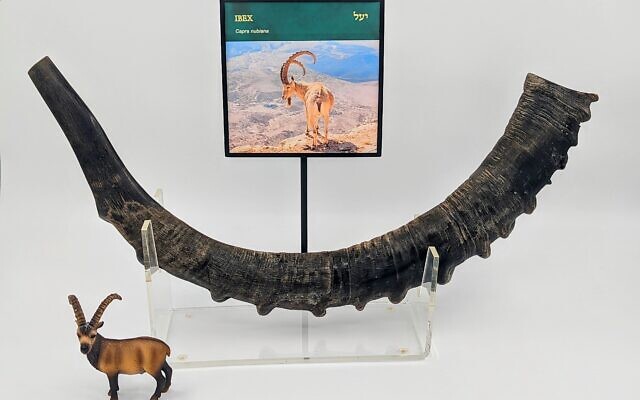

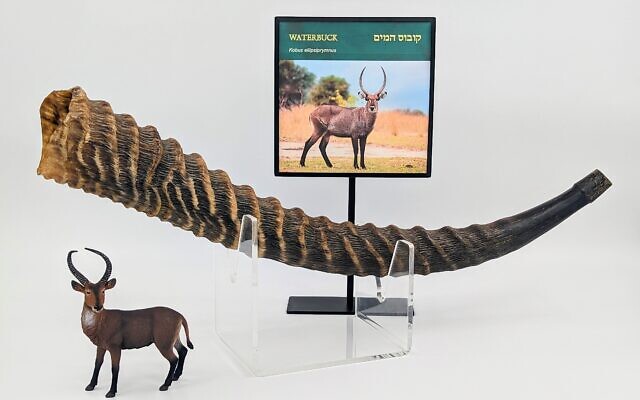

For millennia, people have been crafting horns into shofars. But not every kind of horn can be made into a shofar. An extraordinary exhibit in the Biblical Museum of Natural History in Beit Shemesh delves into the captivating world of shofars, showcasing one of the largest global collections of these remarkable instruments from different animal species. It includes straight, curved, spiral, and even impractical shofars of every size and shape, originating from myriad creatures—from the more traditional ram, ibex, and goat to huge shofars made from spectacular antelope such as sable and waterbuck, a uniquely beautiful and surprisingly strong shofar made from an unusual creature called an East Caucasian tur, and many other strange and wonderful horns and shofars.

The horn that gives rise to the shofar must be naturally hollow; this eliminates both rhinoceros horns, which are composed of solid keratin, and deer antlers, which are solid bone. Shofars are made from horns comprised of keratin sheaths surrounding a bony core, which is pulled out. Then, the tip of the keratin sheath is sawed off to create a mouthpiece, and a small hole is drilled into the hollow interior.

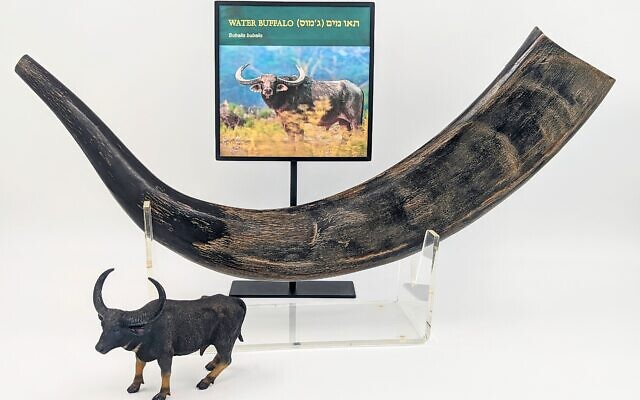

Under Jewish law, cattle horns cannot be used as shofars (the Talmud cites the sin of the Golden Calf) and later rabbinic authorities also excluded the horns of buffalo and other members of the bovine family.

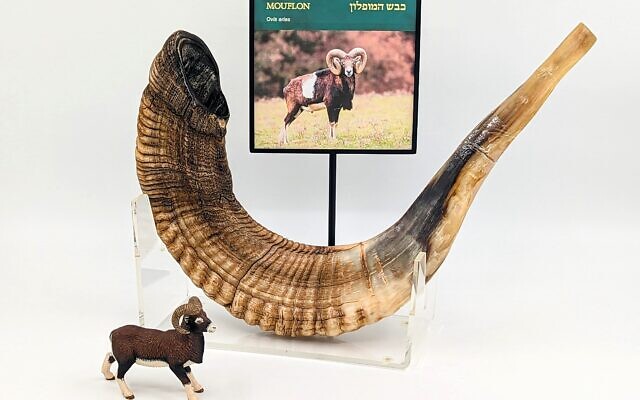

The Talmud also determines that on Rosh Hashanah, one should use a shofar that is bent, symbolizing how we should be bent in contrition on the Day of Judgment. Traditionally and ideally, shofars for Rosh Hashanah are made from ram (adult male sheep) horns. The Talmud explains that they recall how Abraham was willing to sacrifice his son Isaac at God’s command, and instead was told to sacrifice a ram caught by its horns in the thicket. In addition to the more widely used domestic sheep’s horns, the shofar exhibit also features the beautiful horns of the Land of Israel’s original wild sheep, the mouflon, and those of another wild sheep native to this region, the Barbary sheep or aoudad, along with the bighorn sheep of North America’s massively thick horns.

Shofars from pre-Holocaust Europe are often flat, with a carved bell. It seems that many of them were made from goats rather than sheep, for reasons that are unclear; perhaps goat horns were more widely available, since most male sheep are slaughtered at a young age.

The exhibit also features the magnificent spiral horns of the kudu antelope from Africa—the traditionally preferred shofars in certain Yemenite communities. They are widely available today, since kudu are able to leap over the fences of game reserves in Africa and breed freely outside of them without fear of predators.

Other species’ horns, while permissible under Jewish law, are just too impractical to be used as shofars. The exhibit showcases several examples, including the highly twisted horns of wildebeest and other antelopes make removal of the bony core extremely difficult, if not altogether impossible. And the amazing horns of the markhor (a type of wild goat) are such a flat, twisted spiral that turning them into a blowable shofar is a formidable feat.

The exhibit’s non-shofar objects add an intriguing dimension. These have a horn-like appearance (tusks of various animals, from walruses to warthog) or produce a shofar-like sound (conch shells and didgeridoos), but they defy the fundamental principle—a shofar must be made of animal horns.

Some 135 animal species have hollow horns. After excluding a handful of species of domestic and wild cattle and straight-horned species, over a hundred species with curved horns that may be used to make a shofar remain. However, except for the domestic sheep, gemsbok, and kudu, no shofars from these species are commercially available.

Rabbi Dr. Natan Slifkin is the director of The Biblical Museum of Natural History.

comments