The Jews of ‘Stop Cop City’

Jewish protests against Atlanta's planned police training center have struck a raw nerve in the community.

Dave Schechter is a veteran journalist whose career includes writing and producing reports from Israel and elsewhere in the Middle East.

The setting for a Friday night Shabbat service on March 10 was deep in the woods of Intrenchment Creek Park in southeast DeKalb County, beneath a large blue tarp strung between the trees in a section of forest known as the “living room.”

After hours of rain earlier in the day, the ground was soft, the air cool and damp. The only source of heat came from a fire pit dug in the earth. When Rabbi Mike Rothbaum, of Congregation Bet Haverim, a Reconstructionist synagogue in the Toco Hills neighborhood, began singing a niggun, a handful of people joined in.

As the service continued, the congregation, most appearing to be in their 20s and 30s, steadily grew to about 100 people. Some drifted in from clusters of tents and lean-to’s scattered about the woods. Others walked in from a muddy parking lot and along a gravel path. While two or three dozen comfortably recited the prayers in Hebrew, many more read aloud the portions in English.

What drew them to the South River Forest was the March 4-12 “week of action” to protest the city of Atlanta’s planned construction of an 85-acre, $90 million police and fire training center, on 300-plus acres it owns across the city line in DeKalb County. Formally known as the Atlanta Public Safety Center, self-described “forest defenders” derisively call it “Cop City.”

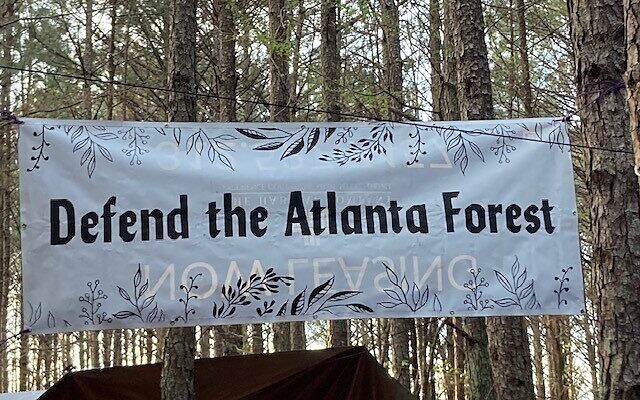

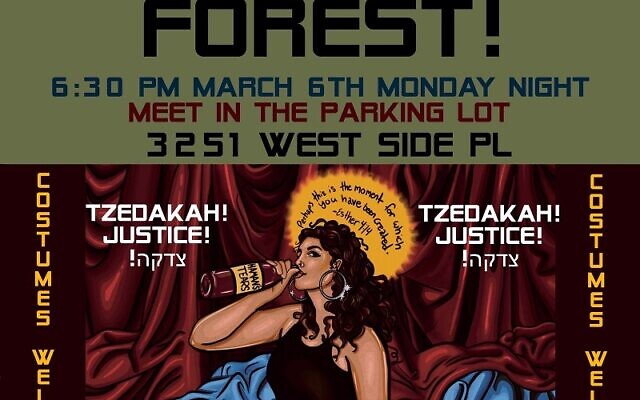

Within the large, decentralized “Stop Cop City” movement a relatively small number of mostly young Jewish Atlantans have expressed their opposition through religious events in the woods, some under the banner of the “Jewish Bird Watcher Union.” They have observed Shabbat and Havdalah, held High Holiday services (including performing Tashlich at the creek), built and occupied a sukkah throughout Sukkot, lighted a menorah during Chanukah, planted trees on Tu B’shvat and gathered for a Megillah reading on Purim.

Within the large, decentralized “Stop Cop City” movement a relatively small number of mostly young Jewish Atlantans…have observed Shabbat and Havdalah, held High Holiday services (including performing Tashlich at the creek), built and occupied a sukkah throughout Sukkot, lighted a menorah during Chanukah, planted trees on Tu B’shvat and gathered for a Megillah reading on Purim.

Their activities — and their politics, including a critical attitude toward Israel — have rankled some in Atlanta’s mainstream Jewish community. “Despicable” was among the adjectives used in emails circulated among communal and religious leaders. The emails, which were provided to a reporter by multiple sources, included a statement of support for the planned training center and a caution to Rothbaum.

Most of the “week of action” took place without incident — the night of Sunday, March 5 being an exception. After dark, roughly 100 people broke away from about 1,000 enjoying a music festival in the park and made their way to fencing at the training center site, where they hurled a variety of projectiles, including some that set fire to construction equipment. Police entered the park, taking into custody 35 people, 23 of whom were charged with offenses that included violating the state’s domestic terrorism law. At this writing, all but one, a legal observer released on bail, remain jailed pending court appearances. All but two were from outside Georgia.

“This group changed their clothing into all black, black-out clothing. They had shields that were like riot-type shields, homemade shields. They had bags of rocks. They had fireworks. They had Molotov cocktails,” DeKalb County chief assistant district attorney Peter Johnson told the court at an initial appearance hearing.

The protestors call the woods “Weelaunee,” meaning “brown water” in the language of the Muscogee (Creek) tribe, for whom the South River Forest was home until about 200 years ago, when they were supplanted by white settlers. The tribe was forced west, to what the federal government called the “Indian territory” in Oklahoma.

The land designated for the Atlanta Public Safety Center has been, over time, the site of a plantation, a Civil War battlefield, and a city prison farm. Police have used sections as a firing range and for explosives disposal. Tires and other debris have been dumped illegally.

Atlanta Mayor Andre Dickens has called the city’s existing training facilities “woefully insufficient.” The planned center would serve the police and fire departments, the 911 call center, and K-9 units. Plans include a shooting range, a “mock city” (with a gas station, motel, home, and nightclub), and a “burn building.” The city has said that the remainder of its property will be developed for recreation use.

Much of the “Stop Cop City” activity has taken place in Intrenchment Creek Park, which draws its name from the creek separating it from the city property. Legal challenges have halted a land swap in which DeKalb County gave 40 acres the 136-acre park to the now-former owner of a film studio, whose crews leveled trees and tore up a paved path before an order was issued to halt work in the so-called “film site.” The areas in question are within a triangle formed by Key Road SE, Bouldercrest Road, and Constitution Road SE.

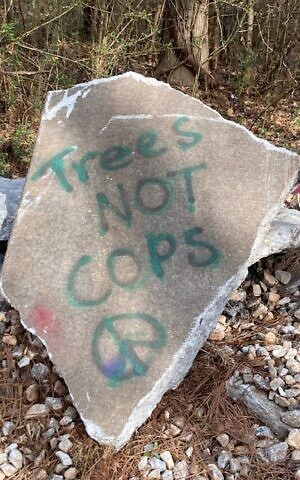

While one theme of the protests has been the militarization of police — that the training site will teach “urban warfare” tactics that will be employed against minority communities — another has been environmental. Community groups in the nearby majority Black neighborhoods worry that any development will worsen flooding in low-lying areas. Conservationists warn that Atlanta — the “city in the forest” — will lose more of its tree canopy.

“This is Atlanta, and we know forests. This facility will not be built over a forest,” Dickens told a January news conference. “The training center will sit on land that has long been cleared of hardwood trees through previous uses of this site decades ago.”

When the Atlanta City Council received 17 hours of public comment before approving the project in September 2021, an estimated 70 percent was negative. The city (which leased the land to the Atlanta Police Foundation as the developer) and DeKalb County have been criticized for what opponents say is a lack of transparency.

Local protests began a couple of years ago. National and international attention has grown since Jan. 18, when a protestor camping in the woods was killed during a police “clearing operation.” The Georgia Bureau of Investigation said that Manuel Esteban Paez Terán fired a handgun, wounding a Georgia State Police officer, before being killed by return fire. An independent autopsy determined that the 26-year-old known as “Tortuguita” was struck by 13 rounds, apparently while seated. Jewish activists said that questions about Teran’s death — the GBI has not issued a final report — deserve as much attention as vandalism of construction equipment.

The sukkah remained standing for weeks after Sukkot, until a Dec. 13 police raid on protestors camped in the forest. A photo posted on Twitter showed the dismantled structure. Activists blame crews working for the film site’s would-be owner for the disappearance of a large menorah from the Intrenchment Creek Park’s parking lot.

The young Jewish activists say that they feel religiously, politically, and ideologically apart from the mainstream community, in terms of how they practice their Judaism and, on such issues, as Israeli policies regarding the Palestinian Arabs (some readily identifying as anti-Zionist).

Thus far, Atlanta’s congregations and communal organizations have not engaged publicly on the issue. The participation of Jewish Atlantans in the “Stop Cop City” movement has struck a raw nerve, as evidenced by an email exchange directed at Rothbaum, who also took part in the Tu B’shvat tree planting and in a March 11 memorial service at which Teran’s family sprinkled their ashes in the forest.

In one email, Jay Kaiman, president of The Marcus Foundation, wrote: “To fall victim to the deception of these activists’ smear campaign today is to allow yourself to become a victim of a real emergency tomorrow, one where our first responders lack the training and tactical skills needed. A well-trained public safety officer can make the difference between a brief crisis and a life-ending tragedy—that’s why we need the Atlanta Training Center.”

Rothbaum’s reply included: “There are a number of our congregants who have grave concerns about this project, and who have been involved in activism regarding its construction. I take their opinions very seriously. In addition, Victoria Fulcher Raggs, Executive Director of the Atlanta Jews of Color Council, has expressed similar concerns. Part of my learning in trying to support Jews of Color has been to take their concerns seriously — as Jewish concerns.”

Rothbaum concluded: “I pray that Atlanta will emerge from this controversy as a city that offers safety and opportunity for citizens of all ethnicities and economic classes, in every neighborhood. May God inspire us to achieve that goal, soon and in our days.”

In response, Kaiman told the rabbi: “You have created [an] adverse relationship with local law enforcement . . . Think hard about the path you are pursuing as a leader of the Jewish community. Anyone of these law enforcement officers would take their lives to protect you.”

An email sent March 14 to members of Bet Haverim, by Rothbaum and congregation president Lauren Levin, spoke indirectly to Kaiman’s admonition: “We greatly appreciate local and state law enforcement for the reliable protective services they provide the Atlanta Jewish community, especially in a time of increased antisemitism. We are deeply grateful especially for the services of DeKalb County Police Department, many of whom we know on a first-name basis. It was, in fact, Rabbi Mike who asked that we thank them by name at each service.”

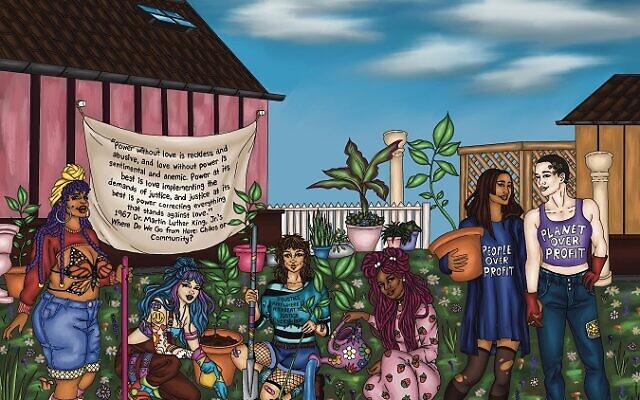

Two of the activists, Ayeola Omolara Kaplan and Adam Brunell — “a queer Black woman [and] a white agender person” — recently published an article on the online site “Atmos” titled “Why Cop City Goes Against Jewish Values.”

They wrote: “For many Jewish Atlantans like ourselves, our Judaism is deeply tied to the effort to defend the forest from Cop City — and the interlocking issues it raises: climate justice, police militarization and violence, nature conservation, and racial justice…As Jews, we have stood in solidarity with the Black community in Atlanta before. It is now time for us to do so again. This is not just a question of Jews standing in solidarity with another community. It’s also about Jewish people standing up for each other: Black Jews are impacted by this, too.”

For many Jewish Atlantans like ourselves, our Judaism is deeply tied to the effort to defend the forest from Cop City — and the interlocking issues it raises: climate justice, police militarization and violence, nature conservation, and racial justice…As Jews, we have stood in solidarity with the Black community in Atlanta before. It is now time for us to do so again. This is not just a question of Jews standing in solidarity with another community. It’s also about Jewish people standing up for each other: Black Jews are impacted by this, too.

Kaplan, a 24-year-old self-described “revolutionary surrealist digital painter,” grew up at The Temple and now is a member of Bet Haverim. “While my family was secular, I never approached religion that way and was always deeply spiritual. It wasn’t until college, when I minored in religious studies, that I began to fall in love with Reconstructing Judaism and the possibility of being in Jewish community again. Now, many of my friends are Jewish and it’s really special to be aligned in that way with the people I love,” she said, adding that, “It was other Jewish radicals that helped me feel comfortable coming to the forest and getting more involved. If I am remembering correctly, my first time visiting the forest was during a Rosh Hashanah event that I helped organize with other eco-spiritual Jews.”

She connects the Atlanta forest to events thousands of miles away. “Yes, many Jewish activists, including myself, connect this issue to Palestine, in that this police training facility would not just be a center to train Atlanta police, other police and law enforcement would travel to this facility. Many police officers also receive training in Israel. This cop city would be a further step in united oppression against the most marginalized,” Kaplan said. “I also believe both Palestine and Atlanta are occupied territories, never ceded by their native occupants. In Israel, they’ve made a practice of uprooting olive trees as a process of the occupation and efforts to push out Palestinians. I think this is similar to the ways the removal of the forest will work to push out the surrounding Black community via flooding or just discomfort in being near such a large police training facility.”

Brunell, 32, grew up in a Reform congregation in Connecticut and joined Bet Haverim after moving to Atlanta last July from Austin, Texas. They have been active in the Jewish events in the forest and in canvassing people in the nearby neighborhoods. Asked how the Atlanta Public Safety Center/”Cop City” issue ends, they said: “There is definitely a pathway, without a doubt, in which Cop City does not get built. If things go a certain way. We’re going to roll the dice, try our best. . . I think it would be ludicrous to even say that no such pathway exists. And that to me is what’s important.”

- News

- Local

- Dave Schechter

- Shabbat

- Intrenchment Creek Park

- Cop City

- Rabbi Mike Rothbaum

- Congregation Bet Haverim

- toco hills

- South River Forest

- Atlanta Public Safety Center

- Jewish Bird Watcher Union

- high holiday services

- Sukkot

- tashlich

- Megillah

- Tu B'shvat

- Purim

- Peter Johnson

- Weelaunee

- Muscogee (Creek)

- Mayor Andre Dickens

- Atlanta Police Foundation

- Georgia Bureau of Investigation

- Manuel Esteban Paez Terán

- Tortuguita

- Jay Kaiman

- Ayeloa Omalara Kaplan

- Adam Brunell

comments