What’s Jewish About … Handbags?

Following World War II, the Budapest-born entrepreneur Judith Leiber came to America and took the fashion accessory industry by storm.

Robyn Spizman Gerson is a New York Times best-selling author of many books, including “When Words Matter Most.” She is also a communications professional and well-known media personality, having appeared often locally on “Atlanta and Company” and nationally on NBC’s “Today” show. For more information go to www.robynspizman.com.

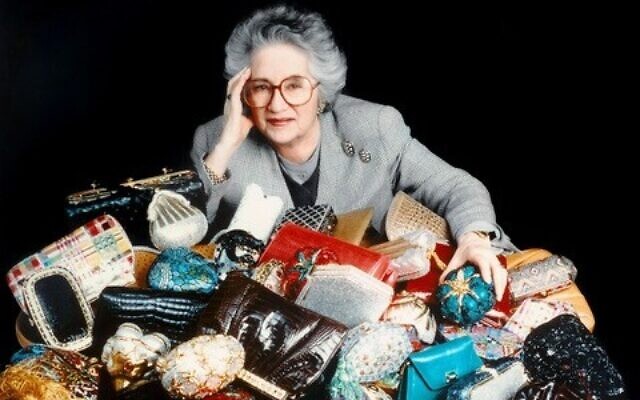

World-renowned haute couture handbag designer Judith Leiber changed fashion history forever. Following World War II, the Budapest-born entrepreneur came to America and took the fashion accessory industry by storm.

Declared an artist by Geoffrey Beene and heralded as a fashion icon, Leiber was perhaps best known for the exclusive purses she fashioned for Presidential First Ladies. The AJT spoke with Ann Fristoe Stewart, director and curator of The Leiber Collection Museum and Sculpture Garden, to learn about the designer’s Jewish roots, life and legacy.

Tell us about how Leiber got started making handbags.

Judith Leiber was born Judit Pető in Budapest, Hungary in 1921. She escaped the Holocaust to the safety of a Swiss House when she was able to get her father a Swiss Schutzpass, a document that gave the bearer safe passage, now on view at the National Holocaust Museum in Washington, D.C. After the war, she began making handbags at home and in a friend’s small factory. She married American soldier Gerson Leiber, emigrated to the U.S. in 1946 and in 1963 founded her own company, establishing herself as an industry leader of luxurious fashion and retiring in 1998.

What’s most famous about Leiber’s handbags?

Sold at exclusive boutiques worldwide, her handbags cost several thousand dollars and have become a status symbol for many women, including Presidential First Ladies, Hollywood celebrities and royalty. Movie stars, princesses, queens and First Ladies from Mamie Eisenhower to Laura Bush carried them, and Barbara Bush and Hillary Clinton had miniaudiéres fashioned as Millie and Socks, who reigned as America’s First Dog and First Cat. In 1994, Leiber received a Lifetime Achievement Award from the Council of Fashion Designers of America. Her handbags are on permanent display at the Smithsonian Museum, the Metropolitan Museum, the Victoria and Albert Museum and many others.

Tell us about Leiber’s childhood and Jewish background.

In 1918, Judith’s Jewish parents, Emil and Helene, had fled Béla Kun’s Communist revolution, seeking safety in Vienna, the city where her mother had grown up and where her grandparents owned a successful ladies’ hat factory, Spitzer Hat Factory. The Petős returned to Budapest shortly before Judith’s birth, and her father Emil rebuilt his career as a commodities broker with a bank. Judy’s family was well-to-do, sophisticated and cultured. From a young age Judith and her sister Eva would admire their mother’s handbags, which their father bought during his business trips to Eastern Europe.

Because of Hitler and the antisemitic atmosphere, including Hungarian laws increasingly restricting the civil and human rights of Jews, Hungarian Jews were prevented from working in certain professions, but were allowed a trade. Judith learned how to make a fine handbag from start to finish and by 1944 she had become the first woman master handbag designer. She said, “Hitler made me a handbag designer.”

By March of 1944, Hungary was occupied by the Nazis and life became almost unbearable. Judith said, “Once the Nazis came to Hungary and occupied it, you couldn’t work. You couldn’t do anything … we were lucky to be alive.”

Two of her uncles were shot by the Danube when they ventured out and her father was taken off the streets and sent to a labor camp to dig trenches against the Russian tanks. Some of Judith’s relatives in France were sent to Auschwitz and many of Budapest’s Jews were herded into a ghetto where food ran short as the Soviets neared.

A girlfriend of Judith’s had an uncle who worked in the Swiss Consulate and, through him, Judy was able to get a Swiss Pass for her father, giving him protection. A 16-year-old boy at the Swiss House, Thomas Baroth, recognized the typeface on the Swiss Pass protecting Judith’s father, found a typewriter with that same typeface and added “and family,” thus saving the entire family from certain death. Judith designed handbags in her head to keep sane as the bombs exploded all around her. “I tried to fall asleep by dreaming of making handbags,” she said.

The owners of Pessel handbags had been deported and Judith and her father decided to sneak into the American Legation to see if they could get emigration papers. On their way, a shell exploded and Judith’s left arm was hit with shrapnel.

The ghetto doctor said that she would never use her hand again, but her mother had heard of a Jewish surgeon who was able to remove the shrapnel and heal Judith’s wound, although the scar remained for the rest of her life to remind her. In February of 1945, the Russians liberated Hungary and the Leibers survived.

Visit www.leibercollection.org for more information.

- Robyn Spizman Gerson

- What's Jewish About

- Opinion

- Judith Leiber

- handbags

- fashion

- World War II

- Geoffrey Beene

- Ann Fristoe Stewart

- The Leiber Collection Museum and Sculpture Garden

- Judit Pető

- National Holocaust Museum

- Gerson Leiber

- Mamie Eisenhower

- Laura Bush

- Barbara Bush

- Hillary Clinton

- Council of Fashion Designers of America

- Smithsonian Museum

- the Metropolitan Museum

- the Victoria and Albert Museum

- Spitzer Hat Factory

- nazis

- Budapest

- American Legation

comments