Yahrzeit: More Than a Date on the Calendar

The thoughts and memories prompted by the anniversary of his father’s death help Dave keep him alive within.

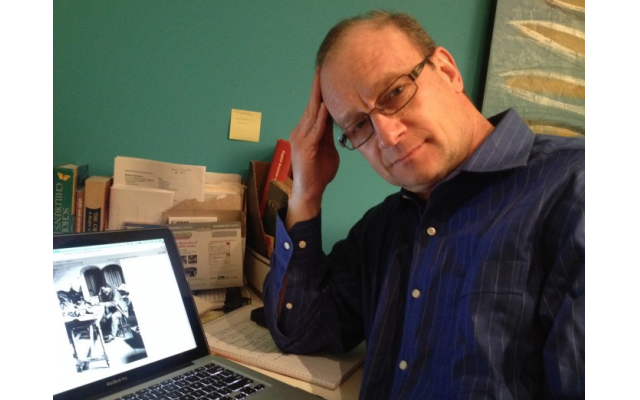

Dave Schechter is a veteran journalist whose career includes writing and producing reports from Israel and elsewhere in the Middle East.

When my sister called to say that Dad had died, I was northbound on Interstate 75 in Florida, returning to Atlanta from a road trip to watch our older son play a collegiate soccer game.

My father, whose physical and mental capabilities had declined the previous two or three years, had collapsed the day before and been taken to a hospital.

With our younger son in the back seat, it took all the focus I could muster to turn off at the nearest highway rest stop. We sat there for close to an hour, until I regained sufficient composure to complete what became a quiet and reflective drive home.

All of this came to mind when our congregation emailed me a reminder of my father’s approaching yahrzeit. On the Hebrew calendar, in the month of Cheshvan, the anniversary this year fell 10 days before the corresponding date in late October.

Daniel Solomon Schechter was 86 when he died nine years ago.

We still talk often. Admittedly, the conversation is a bit one-sided, but that’s okay. I hear his voice.

Among the items that decorate the desk, walls, shelves, and window ledge in my home office are photographs of my father and mementos that remind me of his influence on my life.

He is why I became a journalist and developed my personal set of professional ethics. He is why I played tennis and swam, though neither with competitive success. He is why I was a baseball fan and why baseball lost its appeal when he died.

My father was of the generation that did what it needed to do — “You make do” may have been a mantra — and beyond what we children heard at the dinner table, there was a great deal about his life that we did not know.

Conversely, I sometimes think that my generation shares too much. My children know far more of my life history than I knew of my father’s at their age.

Dad was 11 years old when his father died, leaving him to be raised by his mother and aunt. I was about 12 when he told me, in response to my asking, that his father had two sisters.

The older one moved to South Africa and the younger was a Socialist who was arrested in a strike in North Carolina. That was all he said.

I learned later that the older one transformed herself from the proper wife of a Jewish barrister into an anti-apartheid activist.

Dad was surprised when my research — sparked by a letter that he received from an Emory University professor — revealed that his father’s younger sister was a card-carrying member of the Communist Party throughout her adult life. She wasn’t just arrested, but stood trial for murder and other crimes after the Gastonia police chief was killed during the 1929 Loray Mill strike.

As might be expected, the reminder of Dad’s yahrzeit prompted a variety of thoughts and memories.

In the late 1980s, I wielded a video camera as he gave me a tour of “his” New York, including the address on West 115th near Broadway where he grew up in a 12th floor apartment. Attempting to reach the roof, to show me where he would sit as a boy and throw a rubber ball against a low wall, Dad inadvertently set off an alarm in the building, which now housed Columbia University students. Father and son rode the next elevator down to the lobby and walked out as if they were none the wiser.

I cannot listen to the portion of the Kiddush that follows the blessing of the wine without closing my eyes and seeing my father at the kitchen table, holding his worn siddur, and hearing him chant that prayer. He was an observant Reform Jew and a dedicated student of Judaism.

Dad delivered advice succinctly. Nearing graduation from college, I told him that I felt myself at a crossroad, uncertain whether to apply to graduate school or seek a newspaper job. “Get out of the road before you get run over,” was his response. Make a decision and get on with it.

A yahrzeit is more than a date on the calendar. It is an opportunity to remember the life of an individual, to honor and appreciate their contributions to your life. By doing that, a part of them remains alive. In you.

comments