1867: The Temple’s First Rosh Hashanah

Rapid growth in Atlanta's Jewish population after the Civil War made the time right to start the synagogue.

On Sept. 5, 1867, the following appeared in an Atlanta newspaper. Sounds much too familiar.

“It is alleged in a Washington special publication that President Andrew Johnson has organized a system of espionage upon the conduct of members of Congress favoring impeachment by means of a corps of secret detectives, who are paid out of the secret service.”

Four weeks later, the newly incorporated Hebrew Benevolent Congregation held its first High Holiday services. Those initial members had to wonder what was transpiring with their Republican president, the successor to the slain Abraham Lincoln.

Get The AJT Newsletter by email and never miss our top stories Free Sign Up

1867 was a very good year for the women of Atlanta. The washing machine had been invented 10 years earlier, but a giant advertisement in the Atlanta Intelligencer focused on the new, advanced model that “would make every woman’s life much easier.”

The entry of this device into the lives of the Jewish women in Atlanta — there were about 45 at the time — showed them that the Civil War was completely over. They could move on with their lives and await new inventions for the home, which were coming out almost every day.

Dr. Steven Hertzberg, the author of the most definitive history of Atlanta Jewry, “Strangers in the Gate City,” noted how the Atlanta Jewish population grew from 50 to 400 from 1865 to 1867, the immediate years after the Civil War.

The Jews responded to the American economic expert who pointed out “that Atlanta was a boomtown.” The original Jews in Atlanta were merchants, box makers, candy producers and a few other occupations. Hertzberg wrote that “the Jews of Atlanta” finally had a stable minyan in 1862, so from 1862 to 1867 Rosh Hashanah services were conducted in various rental facilities.

Professor Mark Bauman, the outstanding historian of Jews in the South, wrote me that a synagogue does not exist until it is incorporated. That is what happened with the Hebrew Benevolent Society.

For those first five years, it was a prayer group with no other functions, and no incorporation was attempted. Attorney Samuel Weil filed the petition for the legal creation of the synagogue. A copy of the official request appeared in the Atlanta Intelligencer five times from the end of March until the end of April in 1867.

Torah scrolls were borrowed from congregations in Savannah and Augusta, where the synagogues predated the Civil War.

In regard to Savannah Jewry, a number escaped to Atlanta because of the spread of disease in 1852, and more came during the Civil War.

What else was transpiring in Atlanta in 1867? Most important, Atlanta became the capital of Georgia a few years later in 1870. Second, there were elections in Atlanta, and the mayor was Luther J. Glenn.

The leading Jew in the Gate City was David Mayer. He moved to Atlanta in 1850 and opened a dental practice. He then became a clothing merchant. In 1860 he volunteered and was inducted into the Confederate army. He and Henry Hirsch of Marietta were two of the best-known Jewish soldiers.

One of their comrades in arms was Max Neugas of Sumter, S.C., who was captured at the Battle of Gettysburg and taken to Fort Delaware on Pea Patch Island. He began to sketch scenes in and out of the fort. As a result, he received more food and easily survived. After the war, he moved to New York and became a professional artist. His drawings and paintings are quite valuable today.

What did it take for Atlanta Jewry to decide to establish a synagogue? One of the key people, who lived in Philadelphia, was the Rev. Isaac Leeser. He had established a magazine known as The Occident. Twice he came to Atlanta after the Civil War to conduct weddings.

According to the historians of The Temple, Rabbi Leeser tied the knot for Emily Baer and Abraham Rosenfeld on Jan. 1, 1867.

Rabbi Leeser suggested forming an official congregation in Atlanta.

He hoped the synagogue would become part of the traditional group in America, but after Rabbi Leeser died, Isaac Mayer Wise persuaded the Hebrew Benevolent Congregation to affiliate with the Reform movement.

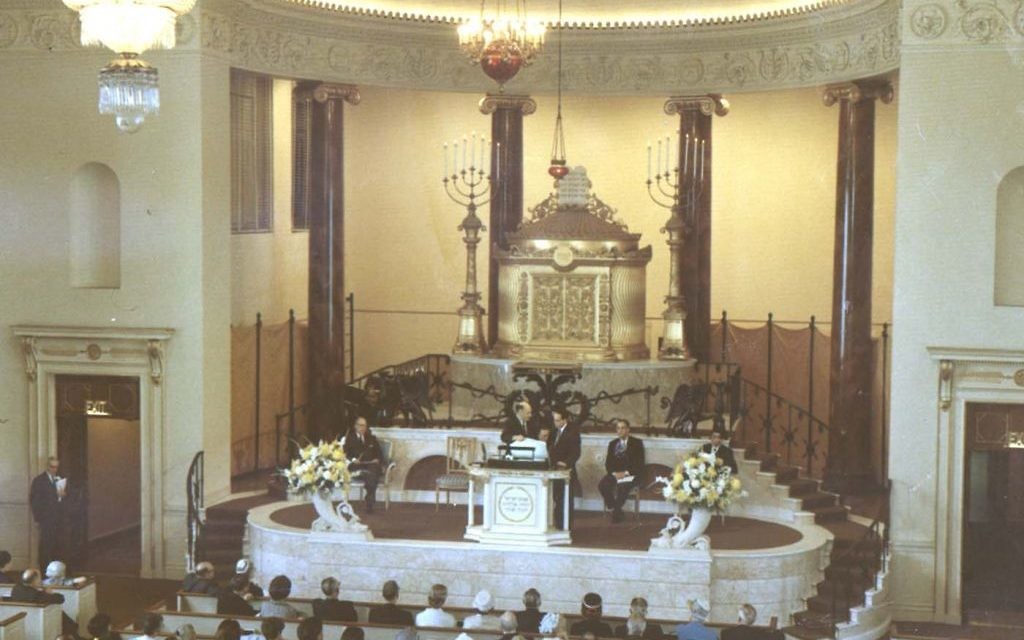

Until Rabbi David Marx’s arrival in 1895, The Temple vacillated in its ideology. Rabbi Marx officially marked the synagogue as Reform, which it has been the past 122 years.

Information about Rosh Hashanah 1867 was gleaned from the writings of Janice Rothschild Blumberg and Hertzberg and the Atlanta Intelligencer newspaper.

Hertzberg writes that for the few years of its existence, “the Hebrew Benevolent Congregation adhered to the traditional ritual … service chanted entirely in Hebrew by knowledgeable members like Jacob Steinheimer, L.L. Levy and William Silverberg.”

Men and women did not sit together, and no instruments were used.

Hertzberg and Blumberg both refer to services held at the Masonic Hall in 1862.

A newspaper pointed out the High Holiday services were “observed with imposing religious ceremonies … by this most ancient denomination of people.” By 1866, the Atlanta Intelligencer described both Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur services.

On that basis, let me suggest who attended that first Rosh Hashanah service in 1867. First of all, it appears that L.L. Levy chanted the main service on Rosh Hashanah, which was Mussaf, a late-morning service with many piyyutim (poems).

The Torah was read by Jacob Steinheimer. He chanted the regular portion from Genesis in one Torah, then the portion from Numbers in the second Torah. David Rosenberger raised the first Torah; I’m not sure about the second one. William Steinberg chanted the Haftorah on both days.

David Mayer, Herman Haas and M. Saloshin were seated on the first row; M. Wittgenstein, Aaron Haas and A. Hirshberg were on the second. Aaron Alexander and M. Lazaron were in the third row. Julius M. Alexander was on the fourth row.

The rest of the congregation spread throughout. Samuel Weil, the lawyer, was given a very nice seat. Also present were the Selig brothers, Levi Cohen, Solomon Dewald, Moses Frank, Morris Hirsch, Abraham Rosenfeld, Morris Wiseberg, Jacob Elsas and Isaac May.

The young people present had been given religious instruction by the wives of Aaron Alexander and Simon Frankfort. They sang the prayers they knew with gusto.

These questions remain: Did the members of the congregation fall to the floor when certain prayers were recited? Did the members go to a wooded section with natural springs and throw in bread crumbs for Tashlich?

There is a story in the “Sunny South” in early 1870s about a shohet who lived 20 miles outside Atlanta. He was visited by many Atlanta Jewish individuals, who bought kosher meat for themselves.

It is a privilege for me to write about the oldest Jewish institution in Atlanta. A Shecheyanu from Jerusalem with hopes for another 150 years of religious stimulation for your congregants.

comments