A Sterling Collection’s Silver Linings

Chana tours Malka Schwab’s extensive collection of silver miniatures.

Chana Shapiro is an educator, writer, editor and illustrator whose work has appeared in journals, newspapers and magazines. She is a regular contributor to the AJT.

There’s an enticing sense of discovery as one approaches the home of Malka Schwab. The long driveway runs past an elaborately gated front entrance and continues to the hedged parking area in the back. Schwab cheerfully greets visitors at the bright blue door, which opens to an art-filled sitting room. The house is a gallery of signed Chagall prints, antique etchings, Jewish ritual objects, a village of handmade polychrome ceramic cottages, Chinese chests and chairs, luxurious oriental carpets, exotic plants and, in wall alcoves, vases of Middle Eastern blown glass. It is the home of an aesthete.

The elegant dining room stars Schwab’s trove of silver miniatures, some quite tiny, which span time periods, cultures and geographic regions.

“I no longer actively collect as I used to when my husband, Edward, was alive,” Schwab says. “I still look at auction websites for unusual handmade silver pieces that are intricate and diminutive, but I don’t bid on them. I’m interested in the handwork and individuality of each one, along with its value in silver quality, provenance and rarity. In the past, when I found something compelling and culturally interesting, I would focus my collecting on that genre. My husband and I each had our own special interests.”

An example of her genre-specific collecting is a glass case filled with small, decoratively pierced silver baskets from the Netherlands. Schwab explains that these are high-quality samples that European silversmiths displayed in their shops. Customers would order replicas in a size that suited their needs. “Some would be duplicated as bread baskets,” Schwab explains, “and others would be made for candy or chocolate dishes or to serve cake. Personally, I love the miniatures best, but I also own examples of larger copies.”

Some of the rarest small pieces in the Schwabs’ collection are an English traveling nutmeg grater; a French vinaigrette container, which was worn centuries ago around one’s neck to mask odors from ubiquitous sewage and garbage; a Dutch mustard jar which held the once-expensive commodity; and an eight-piece 18th century American demitasse set, still in pristine condition.

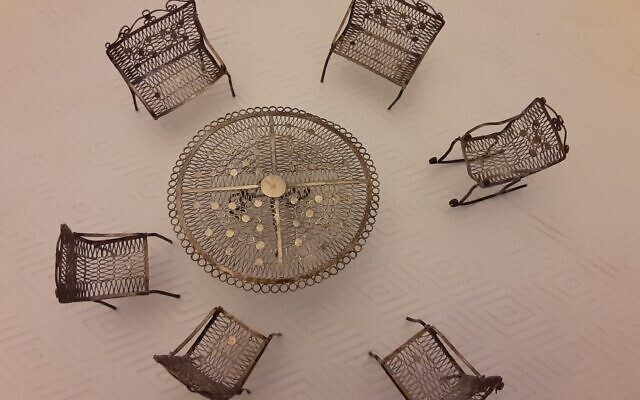

A mahogany breakfront displays an ancient silver and crystal French perfume bottle, ornate Dutch Havdalah spice boxes with moving parts, an Austrian trinket box for jewelry, coins or keys and a miniscule, filigreed set of a table, chairs and benches, purchased by a relative in postwar Indonesia.

Across the room, a large glass case holds three antique Russian Jewish ritual wedding rings, which open and hold a pinch of spice. Schwab’s late husband, Edward, purchased several sets of silver boxes made to hold tefillin, and at an auction, acquired a sterling silver circumcision clamp.

Schwab takes out three silver dreidels. “Two are very, very old,” she says, “and the tiniest one is from the Israeli army.” Among pieces of Yemenite silverwork are a filigree spice box and tzedakah box.

“The flexibility of the purest silver, which is soft, allows artisans to create intricate items,” she explains, “and the addition of alloys to the silver makes pieces more durable, so the amount of alloy makes something stronger and therefore less fragile.” This is evident from the sturdy Dutch sample baskets, as opposed to intentionally decorative creations like the Indonesian table-and-chairs set.

Schwab claims that the purest silver is Japanese and Mexican, with Dutch, for instance, being less pure. The purity of silver is determined by a numeric scale, with 1,000 as the highest. Pure silver gets a 999 rating. In order for silver to be classified as sterling, it must be at least 92.5 pure, thus rated at 925. That means 92.5 percent pure silver and the rest alloy, which can include zinc, copper or nickel. While the United States and most of the world enforce a strict standard of sterling silver at 92.5 percent silver to 7.5 percent copper or other alloys, other countries have their own standards. For instance, the French silver standard for sterling is 95 percent, or rated at 9.50.

When asked if she would sell or trade any of her treasures, Schwab responds, “Edward and I had a double purpose in our purchases. First, to build a substantial collection of handmade silver objects that we love and treasure, and second, to locate valuable pieces to sell to other collectors. We traveled in Europe and Israel, spent many hours at antique markets and auctions, and we found some exceptional things on eBay. We always did a lot of research and continued to learn more. Our expertise and discernment grew as our collections grew.”

- Treasure Trove

- Community

- Chana Shapiro

- Malka Schwab

- sterling silver

- ritual objects

- baskets

- miniatures

- nutmeg grater

- spice boxes

- wedding rings

- tefillin cases

- silversmith

- oriental carpet

- Yemenite jewelry

- Indonesia

- demitasse set

- mustard jar

- trinket box

- blown glass

- Chinese chests

- handwork

- provenance

- auctions

- collecting silver

- filigree

- Israeli army

- perfume bottle

- alloys

- sterling rating scale

- ebay

comments