Conspiracy of Silence

Death is powerful. It demands challenging transitions and thrusts unwanted responsibilities on the bereaved.

The phrase “conspiracy of silence” has echoed through my life.

I first heard it at a conference featuring the Swiss-American psychiatrist Elizabeth Kubler Ross. Her book “On Death and Dying” was groundbreaking because she wrote about five stages of dying and the aftermath of grief for a culture that preferred being secretive about these realities. I already knew something about them.

When my 17-year old brother, Barry, died, I was dumbstruck to discover no one would talk about it, not even my parents, who were shocked into lifelong numbness and an unwillingness to speak about losing their son. It has been 50 years, and my mother rarely speaks his name. A conspiracy of silence can last a lifetime.

Death is powerful. It demands challenging transitions and thrusts unwanted responsibilities on the bereaved.

As I’ve journeyed from marriage to widowhood, I’ve worked hard to live fully. I never know when the grieving gremlin will overtake me and cause me to stop whatever I’m doing and weep. I have no control over what triggers my mourning. Grief is unpredictable.

Rather than be silent about my grieving process, I have broadcast it on social media. I’ve chosen to be emotionally transparent on Facebook.

Many ask why.

I share my journey in the hope of saving others from shock and unpredictability if it happens to them. Social media may be widely ridiculed and seen as a waste of time, but it affords me a place to share complex details and nuanced feelings.

Losing my husband has been the most difficult experience of my life. My intention is to continue living fully while remembering how he filled my heart with love, acceptance and hope. Plus, I want to honor his memory and keep it alive for our grandchildren, who deserve to know how kind, giving and philanthropic he was.

The agony of living through his funeral and the week of shiva was ameliorated by the way my friends and community embraced me.

Life goes on. I kept living.

When it was time to plan Dan’s unveiling, I hit a wall. I felt paralyzed and couldn’t bear the thought of going to the cemetery. An unveiling seemed like the last thing I would ever do as Dan’s wife. I didn’t want to write the last chapter.

How could I select a tombstone and compose his epitaph? I was stuck.

I had no idea how to overcome my resistance. A friend gently urged me to find a way to do what was necessary because the yahrzeit would come around before I knew it.

My rabbi had told me an unveiling is an American concoction. No Jewish law mandates putting up a stone at a specific time. Jewish custom, however, is for a stone to be erected by the first anniversary of the death.

I asked myself what Dan would want.

Dan was traditional and took Jewish customs and laws seriously. My son David, a rabbi, reminded me that the unveiling had to occur before Passover.

I emailed my rabbi, saying I was unable to go to the cemetery and begin the process leading to the unveiling.

His compassionate response was a welcome surprise.

‘Would it help if I went with you?” he texted.

We drove to the cemetery together and walked around, looking at the gray memorial monuments — what people in the funeral industry call tombstones. I read epitaphs and compared the design of the stones and the variations in colors. I took photos of those I liked.

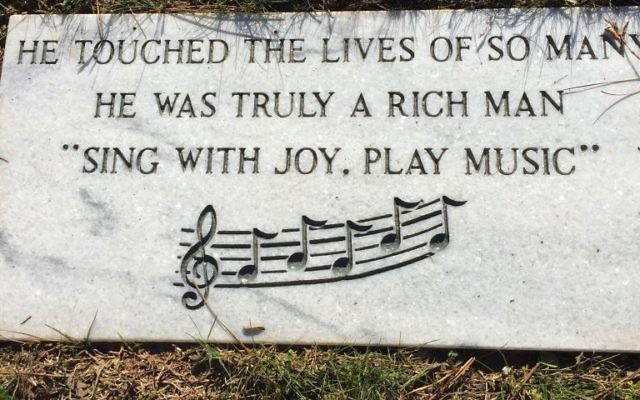

I also noticed footstones, which listed information other than “beloved husband, father and grandfather.” These footstones, in my opinion, reflected the personalities of the deceased.

Although words usually come easily to me, I struggled with the heavy responsibility of choosing words for Dan’s tombstone. Not only was this the last official act I would do as his wife, but also the words would be engraved forever.

After much thought, I made the decisions. The headstone and footstone were ordered. The unveiling was set for the end of March.

I picked white marble for his gravestone. Another difficult decision was whether it would be a double size, leaving half to eventually contain my name and epitaph. Imagining a future time when my children were standing by a gravesite where Dan and I both were buried gave me chills.

This was something I couldn’t discuss with anyone. I finally joined the conspiracy of silence.

comments