In Israel, Holocaust Survivors from Ukraine Ambivalent About Their War-Torn Homeland

Many Ukrainians killed Jews during World War II, collaborated with Nazis, and the country has honored antisemites, while others saved Jewish neighbors, say some survivors.

As a Holocaust survivor from Ukraine, Yaakov Zelikovich is heartbroken over the human suffering in his country of birth amid Russia’s devastating invasion.

“As a Jew and as a person, I feel bad for the children, the women, the anguish,” Zelikovich, an 83-year-old grandfather of four.

And yet, even though he was born and raised in Ukraine and speaks Ukrainian well, he has been living in Israel since 1974 and feels little solidarity with his native land.

“On the national level, I think that it’s their problem, not mine. Believe me, it’s certainly not my problem,” said Zelikovich, citing widespread collaboration by Ukrainians with the Nazis during World War II as the reason for his indifference.

Zelikovich’s antagonism is typical of the ambivalence felt by some Holocaust survivors and others as both Ukraine and Russia consistently reference the Holocaust to rally support for their respective sides during the current conflict.

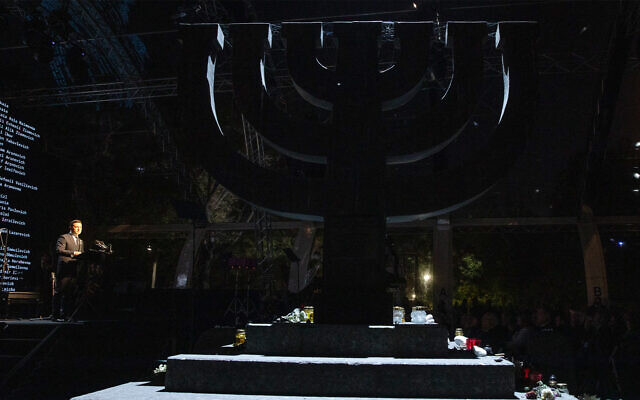

Zelikovich, who lives in Karmiel, spoke with the Jewish Telegraphic Agency on Thursday, Yom Hashoah — the Jewish day of commemoration for victims of the Holocaust, when much of the ambivalence has risen to the surface.

Although some Ukrainians helped save Jews during the Holocaust, “It’s well known that other Ukrainians helped the Germans,” Zelikovich said. “In some cases, by the time the Germans came in, their work had been done for them: Ukrainians killed the Jews to a person and looted their homes.”

Ukraine’s checkered record during the Holocaust, the prevalence of Nazi collaboration there, and the glorification of collaborators today, make for a complicated and often conflicted attitude toward that country by Holocaust survivors from the country, and their descendants.

To Ida Rashkovich, an 86-year-old survivor from the Ukrainian city of Vynnitsa who now lives in Holon, Israel, this is not some abstract discussion about history and geopolitics. Several of her relatives were murdered because of local Ukrainian collaborators, she told JTA.

“Of course I had relatives killed by Ukrainians. But other Ukrainians also saved Jews. It’s a very mixed picture,” she said, adding that she strongly opposes Russian President Vladimir Putin’s “monstrous actions.”

Zelikovich recalls being marched as a child to a mass grave in the woods flanked by Ukrainian police officers, who under the auspices of the Nazi-aligned Romanian occupiers, rounded up the Jews of his town of Tomashpil.

At a certain point, his grandmother, who was marching alongside him, picked him up and carried him toward their would-be execution place. But the Romanians decided to spare adults with children, which is why he and his grandmother, Ida Dolbur, were allowed to return home.

Having narrowly escaped being executed along with more than 200 victims who died that day outside Tomashpil, Zelikovsky’s family went into hiding and survived. Dolbur died in 1953.

“It’s especially hurtful that the leaders of the collaborationists are now celebrated as heroes in Ukraine,” he said.

Ukraine’s fight against the Russian aggressors and the leadership of Ukraine’s president, Vlodymyr Zelensky, who is Jewish, has inspired the West, and undermined Putin’s propaganda describing his war goals as the “denazification” of Ukraine. Before the war, tens of thousands of Jews lived in Ukraine, enjoying a network of synagogues and schools and joining their non-Jewish neighbors in denouncing and resisting the Russian forces.

“Over 30 years we built an amazing community,” Avraham Wolff, a Chabad rabbi in Odessa, told The Washington Post in March. “And it’s a shame that it has come to this.”

Still, over the past decade, Ukrainian society has seen mainstream attempts to glorify World War II collaborators like — Ukrainian nationalists who at least for a time worked with the Nazis against the dreaded Soviet Union. Their troops are believed to have murdered thousands of Jews during the Holocaust.

State-sponsored honors to Nazi collaborators are a new development in Ukraine, where about 15% of the population are ethnic Russians. The phenomenon grew as Ukrainian nationalism consolidated itself politically, and exploded following the 2014 invasion of Ukraine by Russia and Russia’s annexation of Crimea.

In 2017, the city of Lviv held a festival in Shukhevych’s honor. The following year, the city sponsored a parade in which participants marched in the uniform of a Nazi-led unit of Ukrainian conscripts: the 14th Waffen Grenadier Division of the SS, or the 1st Galician.

In parallel, historical figures like Bohdan Khmelnytsky, the 17th-century Cossak leader whose army killed countless Jews, are also being celebrated. A gold-tinted statue of Khmelnitsky is on display in a central avenue of Kyiv named for him.

The Ukrainian National Guard also includes a volunteer unit called the Azov Battalion, which according to its commanders includes a significant portion of neo-Nazis, and whose logo is a neo-Nazi hate symbol.

Zelensky did not help matters when he compared the Russian invasion to the Holocaust, at a time when the fighting was brutal but not genocidal under accepted definitions of the term.

comments