Jews and Italians Battled for ‘The Godfather’

The Jewish production executives at Paramount Studios and Italian Americans like Mario Puzo and Francis Coppola were rarely in agreement during the film’s production.

“The Godfather,” the epic film saga of an Italian American crime family, marked its 50th anniversary this month. Clocking in a total of just over nine hours, the first installment of what would eventually grow into a film trilogy was released on March 24, 1972.

In the intervening decades, the film, as well as its 1974 sequel, have come to represent towering achievements in American film production. In the 1960s, though, it was just another idea in Mario Puzo’s head.

For nine years the author had struggled, writing lurid fiction for a series of men’s magazines with titles like “Male,” “Man’s World,” “True Action” and “Stag.” These magazines were published by Moe Goodman, who was born to Jewish parents originally from Vilna, Lithuania.

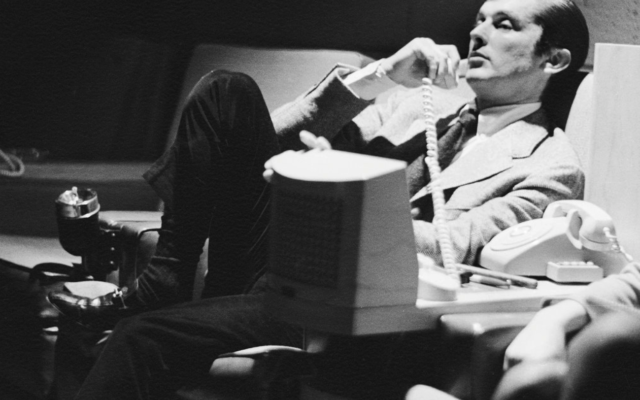

Both Puzo and fellow Italian American director Francis Ford Coppola would get into a protracted and furious battle with the executives of Paramount Pictures, producers of the “The Godfather.” Coppola was only 28, having just penned the script for the film “Patton,” when the head of production at Paramount Pictures, Robert Evans, chose him to direct the adaptation.

Evans, born Robert Shapera, was the son of a Jewish dentist from the Upper West Side of New York City. He gave Puzo just $50,000 for the movie rights to his proposed novel about the rise of his fictional New York mobster, Vito Corleone.

Evans had been handed the task of rebuilding the once-flourishing Paramount Studios by its new owner, Charles Bluhdorn. Bluhdorn had been born to a well-to-do Viennese Jewish family who fled to America ahead of the Nazis in the 1930s.

The hard-charging Bluhdorn had added Paramount to his Gulf and Western Industries conglomerate when the studio was foundering back in 1967. Over the next several years, Evans and Bluhdorn produced a string of popular moneymakers, including “Barefoot in The Park,” “The Odd Couple,” “Rosemary’s Baby,” “True Grit” and “Love Story.” Initially, they and Paramount’s president, Stanley Jaffe, saw the Puzo book as a fast, cheap, modern day gangster movie that could be shot on Paramount’s Hollywood sound stages.

It would take the financial success of the novel and Coppola’s insistence that the film should dwell on the deep historical flaws of American society that caused the trio of executives to agree to up the budget and allow the film to be made on location, with a recreation of 1940s New York.

But the battle over the production schedule, the casting and the direction of the film was just starting to heat up. The tumult surrounding the epic film is fully described by Mark Seal in “Leave the Gun, Take the Cannoli: The Epic Story of the Making of ‘The Godfather,’” which was published in 2021.

The make-believe war between the Corleone mob and its underworld rivals mirrored the constant and very real struggles between Coppola and the executives at Paramount. They now included the film’s producer, Al Ruddy, who grew up in a Jewish family in New York and Miami Beach.

Initially, Coppola had resisted casting James Caan in the role of Sonny, the Godfather’s beloved eldest son. Caan had been born in Queens to German Jewish immigrant parents. Even though the director had pushed hard for Marlon Brando to star, he wanted a mostly Italian American cast.

Seal quotes the casting director, Fred Roos, as saying Coppola wanted “the smell of garlic coming off the screen.” He strongly favored the young actor Al Pacino for the film and had already promised the role of Sonny to Carmine Caridi.

According to Seal, Evans said that Coppola told him, “Carmine Caridi’s signed. He’s right for the role. Anyway, Caan’s a Jew — he’s not Italian.” After months of wrangling, Evans and the other Jewish executives got Caan as Sonny, and Coppola got Pacino as Michael, the younger son, and Brando.

But casting troubles were not the end of the producers’ difficulties. Suddenly, Paramount began receiving serious opposition from a new organization. Originally called the Italian-American Anti-Defamation League, it objected to the stereotyping of Italian Americans as hoodlums and professional killers, especially in Hollywood productions. The organization took inspiration from the success of civil rights organizing in the 1950s and 1960s and from the efforts of the Anti-Defamation League (ADL), which had been organized by the B’nai B’rith to combat antisemitism in America.

The newly renamed Italian-American Civil Rights League quickly raised $600,000 in contributions, organized a charity concert headlined by Frank Sinatra and threatened to shut down production if its series of demands was not met. Ruddy, the producer, with his potential blockbuster on the line, sprang into action.

No stranger to tough negotiations, Ruddy had previously steered a successful CBS-TV network comedy series, “Hogan’s Heroes,” about a group of prisoners of war in a Nazi prison camp, through a sea of controversy. The series ran for six years, despite objections from Jewish groups.

In a series of meetings with the leadership the League, Ruddy agreed to an unprecedented list of concessions that gave them access to the completed shooting script, veto power over any words like mafia and Cosa Nostra and handed over proceeds from the New York premiere of the film. It was a startling agreement, made with organized crime figures, but it also ensured that the extensive location filming required would proceed smoothly.

The mobsters were so impressed by Ruddy’s negotiating skills that they made him a captain in their civil rights organization. But their influence quickly waned when the League’s head, Joe Colombo, was assassinated in New York just ahead of one of the group’s largest rallies.

Both Caan and Pacino went on to be nominated for Academy Awards, while Brando won for Best Actor but declined the honor. The film received the Oscar for Best Film in 1972 and went on to gross $270 million at the box office, which is $1.8 billion in today’s dollars.

Still, after all its success, a decade after the movie’s record-setting release Coppola sent a blistering telegram to Evans, accusing him of taking too much credit for the success of the film.

“You did nothing on ‘The Godfather’ other than anoy [sic] me,” he wrote. “If you want a PR war or any kind of war no one is better at it than me.”

Evans wrote back at some length, saying, “… your behavior toward me glaringly lacks any iota of concern, honesty or integrity. … Do not mistake my kindness for weakness.”

After Evans died in 2019, at the age of 89, the two telegrams sold at an estate auction for $38,400.

On April 20, Paramount+ premieres a ten-part dramatic series, “The Offer,” about the making of the epic film. Watch the trailer: www.youtube.com/watch?v=iowLzO9-aew.

- Arts and Culture

- Opinion

- jewish history

- Bob Bahr

- The Godfather

- Italian-Americans

- Mario Puzo

- Moe Goodman

- Vilna

- Lithuania

- Francis Ford Coppola

- Patton

- Paramount Pictures

- Robert Evans

- Upper West Side

- Charles Bluhdorn

- Corleone

- James Caan

- Marlon Brando

- Al Pacino

- Italian-American Anti-Defamation League

- Italian-American Civil Rights League

- Hogan's Heroes

- Oscars

- Academy Awards

- Paramount

comments