John Lewis Bent the Arc

Ahavath Achim’s former senior rabbis remember the former congressman, sharing personal reflections on their experiences with him.

As we continue to mourn the death of Rep. John Lewis and celebrate his life, we, as rabbis, naturally do so, in part, through the prism of our tradition. Rabbis Arnold Goodman and Neil Sandler, former senior rabbis of Ahavath Achim Synagogue, share personal reflections on their experiences with Lewis. Goodman’s tenure included the first half of Rep. Lewis’ time in Congress; Sandler’s tenure coincided with the second half. Both colleagues are grateful to The Rabbinical Assembly for inviting them to share their thoughts.

The Israelites’ fate was sealed after a rebellion that came in the aftermath of the spies’ report that moving into the Promised Land would be no cakewalk. God punished them duly for their absence of faith, and decreed that none of them then alive, save Caleb and Joshua, would live to see the people’s entrance into the Land of Israel.

For Moses, Caleb was a profile in courage, who calmed the rebellion and then led the community through its 40-year trek and then into Canaan. He assured his disciples Caleb and Joshua, as he prepared himself for his own death, that with faith in God the two of them — and their people — would prevail.

As the former senior rabbis of Atlanta’s Congregation Ahavath Achim, Rabbi Goodman, serving from 1982 to 2002 and Rabbi Sandler from 2004 to 2019, they both had the occasion to work firsthand with the late Rep. John Lewis — a Caleb for our time.

Rabbi Goodman first met John Lewis in 1986 when he was the underdog candidate for Congress. He came around for a morning cup of coffee, and impressed Rabbi Goodman with his candor and humility. His leadership role in the civil rights movement was well-known, and he was widely respected as a champion for human rights issues.

He narrowly won that election, and served in Congress for over 30 years until his recent death. He quickly became the conscience of the Congress and was not only a voice for justice for the African American community, but also for Soviet Jewry, the state of Israel and those who found themselves oppressed and held down.

Some years ago, our Atlanta-area congregation organized a one-day mission to visit the national Holocaust museum in Washington, D.C. Rabbi Goodman contacted John Lewis and invited him to meet with us in the museum’s rotunda. He graciously accepted and spoke with great sensitivity about the Holocaust and the challenge of quashing evil before it takes permanent root. He ended with the affirmation of “Never Again.” We sensed that had there been individuals with Lewis’ passion for justice and with his courage to speak truth to power, the Third Reich might not have taken root in Germany.

Rabbi Sandler saw Rep. Lewis speak before large audiences, interacting with him in large groups and in small settings. Always the same John Lewis. Always the same countenance. Humility that, ironically, was overpowering. He showed none of the guile and modulation so common to men and women who enter into public life.

In meetings, Representative Lewis gave his full attention. “Perfunctory” and “auto-pilot” were not words or expressions in his lexicon. He did not phone it in.

Rep. Lewis focused on people, especially on young people. Rabbi Sandler recalled a meeting in Lewis’ office with about 20 people. Rep. Lewis invited everyone to introduce herself or himself. When he reached the youngest member of the delegation, a teenager, Lewis stopped the flow of introductions. He asked questions of the young man. He probed. He was interested in him, and he appreciated that this teenager had taken the time to visit him in Washington, D.C. And, as always, he encouraged the young man to learn and to “get into good trouble.” A civil rights icon and a man admired by many people treated a young man in his office as if he were the guest of honor in this gathering. What humility!

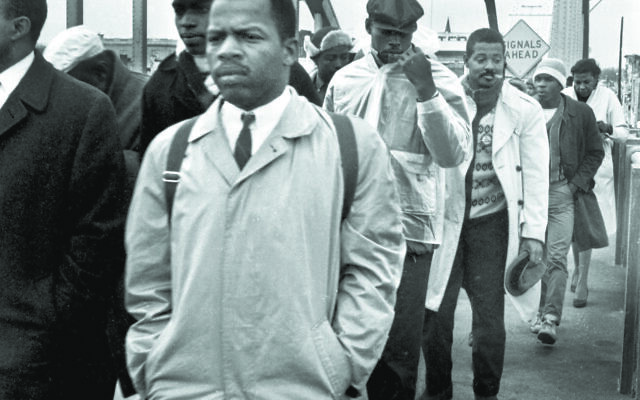

In May 2013 Rabbi Sandler was with Rep. Lewis in his office on a Tuesday. In a rather offhanded manner, he mentioned he would be at the Jewish Theological Seminary in New York two days later. Lewis was excited to go to the institution he associated with a man he greatly admired, Dr. Abraham Joshua Heschel, of blessed memory. Dr. Heschel and Mr. Lewis had made that fateful march together across the Edmund Pettus Bridge in 1965.

Rep. Lewis didn’t tell Rabbi Sandler why he would be going to JTS. Only later that day did we learn he would be receiving an honorary degree and serve as commencement speaker! He was too modest to say exactly why he was going to the seminary. Two days later Rabbi Sandler beamed as he sat in the audience and listened to the congressman. His humility, shaped by the gratitude he felt in being honored by the institution he associated with the man he called “Rabbi Herschel,” was evident to all who were present. We sometimes forget how wide-ranging the humiliation and depredation inflicted on African Americans in the Old South was. During a recent speech at the Georgia Governor’s Mansion, where he appeared to discuss his memoir, “Walking With the Wind,” Lewis reflected on the time that he applied for a library card in Alabama and was turned down. When he grew up, the government was all too often an enemy of people of color. His presence at the mansion of the governor of a historic Southern state was significant, but there was — and is — still a long road ahead.

His is an American story. This son of a sharecropper in rural Alabama rose to be a leader in national and state government. Yet he never backed away from his deep-seated commitment to speak truth to power. He was rightly called the conscience of the Congress; more appropriately, he was the conscience of so many of us. This modern-day Caleb awakened every morning to continue his life work of “bending the arc of history toward justice.”

Completing this task is more than a 40-year trek. It is an ongoing mission to arrive at the day when “Justice shall well up as waters and righteousness as a mighty stream.” (Amos 5:24) May he rest in peace and may his memory and example be a lasting guide to us all.

The Rabbinical Assembly is the international association of Conservative rabbis. Rabbis of the Assembly serve congregations throughout the world, and also work as educators, officers of communal service organizations, and college, hospital and military chaplains.

comments