‘High Noon’: When Politics Echoed in Silence

Glenn Frankel highlights how Red Scare's Hollywood waves washed through the classic Gary Cooper Western.

Silence.

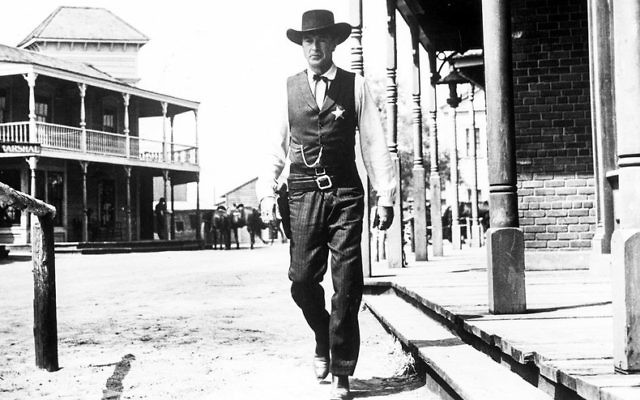

As the clock ticks toward the climactic scene in “High Noon,” the classic 1952 Western starring Gary Cooper, there is only silence on the main street of the dusty backwater where Cooper is the marshal.

All the townspeople who should be joining him to shoot it out with a gang of outlaws threatening the town remain safely behind the drawn curtains in their homes.

But as Glenn Frankel points out in his new book, “High Noon: The Hollywood Blacklist and the Making of an American Classic,” silence also afflicted another small Western town — Hollywood — during a frightening period in American history 65 years ago.

When “High Noon” was in production, the Red Scare was in full swing in this country, and Hollywood was under attack.

Congressional committees, beginning in 1947, had forced a long list of Hollywood writers, directors and stars, many of them Jews, to testify about their political beliefs and the beliefs of their relatives, friends and co-workers.

Eventually the Supreme Court would curb the power of Congress to conduct such investigations, but for many it meant the end of their creative lives and years on a blacklist. Hollywood, as Frankel makes abundantly clear, greeted this concerted attack on civil liberties with silence.

The comparison between the fate of one town in the Old West and another in the mid-20th century is not accidental.

As the director of the film, Fred Zinnemann, put it, “‘High Noon’ is not a Western as far as I’m concerned. It is just set in the Old West.”

For Zinnemann and the other key members of the production team, it was meant to be a metaphor for the paralysis and failure of will when the creative freedom of the industry was threatened by political forces.

Zinnemann, whose Viennese parents perished in the Holocaust, and every other key creative figure in the film’s creation, with the major exception of its stars, were Jews, with a finely honed appreciation of the importance of the Jewish prophetic tradition of social justice.

For the executive producer, Stanley Kramer, whose father was a Zionist and trade union activist, and even the film’s composer, Dimitri Tiomkin, who was a Jewish refugee from Soviet Russia, the film served to make a political statement.

But it was the film’s script writer and associate producer, Carl Foreman, who was the most instrumental in shaping the uncompromising message. He wrote the film as he came under attack by the House Un-American Activities Committee in 1951.

As Frankel pointed out recently, “The marshal was now Carl himself; the gunmen coming to kill him were now the committee.”

“It was insane,” Frankel quotes Foreman as saying. “As I was writing the screenplay, art was mirroring life, and life was mirroring art. I became that guy. I became that Gary Cooper character.”

Ultimately, the political pressure became too much. Just before the completion of the movie, Foreman was forced out of the film and, with much personal bitterness, went into creative exile in London.

A formidable political coalition was determined, as Frankel said recently, “to take America back from so-called usurpers.”

“Back in those days it was liberals and Jews and Communists who were the enemy. Now it’s Muslims, refugees and undocumented immigrants, and the self-appointed guardians of American values were determined to get their country back,” he said.

“I guess,” Frankel concluded, “they wanted to make America great again.”

Despite the intensely political background to the film’s production, it was a runaway hit, to the surprise of almost everyone.

For many filmgoers, the taut narrative, strong performances, and incisive editing and direction of “High Noon” were more important than any political messages that might have been buried in the story.

It was nominated for seven Academy Awards and won four Oscars, including best actor for Cooper and best original song for Tiomkin and Ned Washington for “High Noon (Do Not Forsake Me, Oh My Darlin’),” performed by Western balladeer Tex Ritter.

“High Noon” was selected for preservation by the Library of Congress in the U.S. National Film Registry in 1989, among the initial choices of American films that are “culturally, historically or aesthetically significant.”

Bob Bahr will interview Glenn Frankel and discuss “High Noon” at noon Sunday, Nov. 5, at the Book Festival of the Marcus Jewish Community Center.

comments