Mississippi Jews Cite Camp as Jewish Touchstone

Mixed in with a small number of natives and thousands of Yankees in Atlanta are dozens of Jews from small towns in Mississippi.

Mixed in with a small number of Atlanta natives and thousands of Yankees here in the major metropolis of Atlanta with its population of 5.8 million, are dozens of Atlanta Jews from small towns in Mississippi.

There’s Deborah Lamensdorf Jacobs from Cary, a town of 400. There are Nikki Pollack and sister Stephanie Gordon Kashdan from Canton, a town of about 12,000; Brett Friedman from Indianola, with a population of about 10,000; Kevin Levingston, from Cleveland, that had roughly 15,000 people in the 1970s; Gerald Kline, from Clarksdale, that at its height had a population under 25,000; and Amanda Abrams from Brookhaven, with a population of 10,000. Atlantan Marty Kogon grew up in Meridian, one of the largest cities in Mississippi, with a population of about 40,000.

In each of these cities, however, the Jewish population was infinitesimal. For instance, Abrams said only about 30 Jews lived in Brookhaven, an hour south of Jackson, when she was growing up. “My brothers and I were the only Jewish kids in town. Fifteen minutes away, there was another Jewish family. We had to drive an hour to go to Sunday school.”

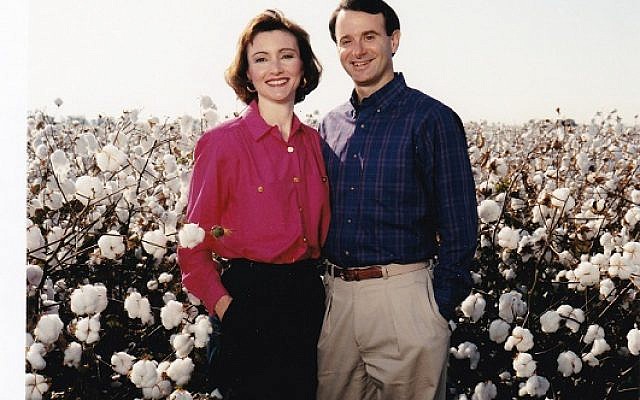

Abrams’ story is not unique for native Jewish Mississippians. Although the Atlanta Jewish community also has a good-sized contingent of Jews who grew up in small Georgia towns, Mississippians are unique in several ways. Imagine, for instance, decorating a sukkah at Temple Anshe Chesed in the town of Vicksburg, located on a stretch of flat, fertile land on the way to Memphis, known as the Mississippi Delta. Jacobs recalled how adaptive the tiny Jewish community had to be; she remembers decorating the sukkah with cotton.

“My great-grandfather bought land in 1919,” she said, noting the 100th anniversary of her family continuously farming the property. At one family reunion, Jacobs said they “made tallis (prayer shawl) covers from the cotton on that first piece of land.”

Probably speaking for many Jews who grew up as a distinctly small minority, Jacobs recounted, “It was a privilege to be a representative of Jews to people in our town. We knew the way we treated people and how we reacted to things had to represent Jewish values. It wasn’t a burden, but we had to be strong and know when it was a teaching moment.”

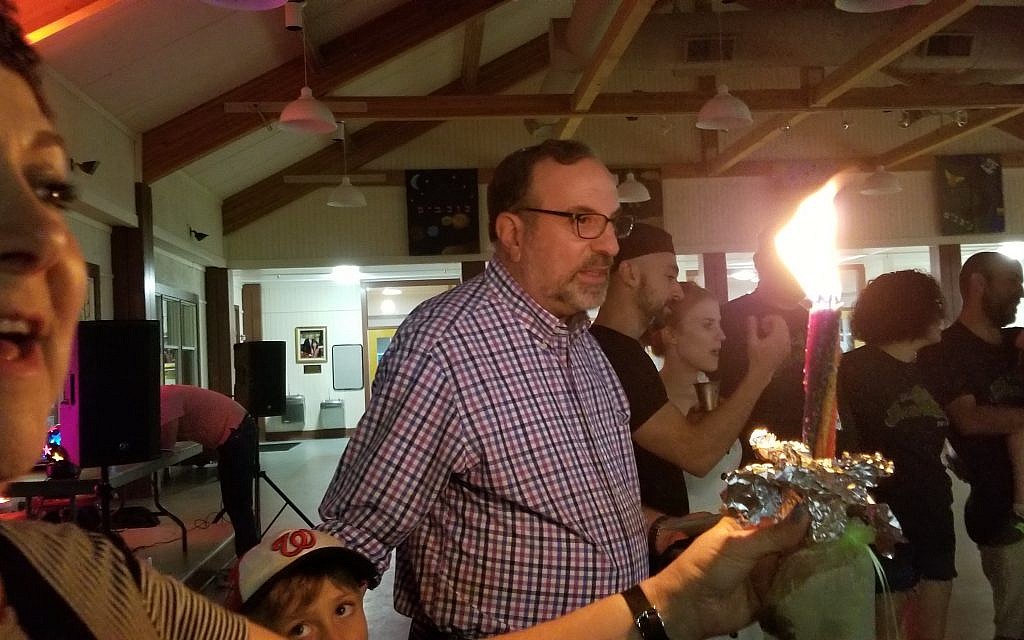

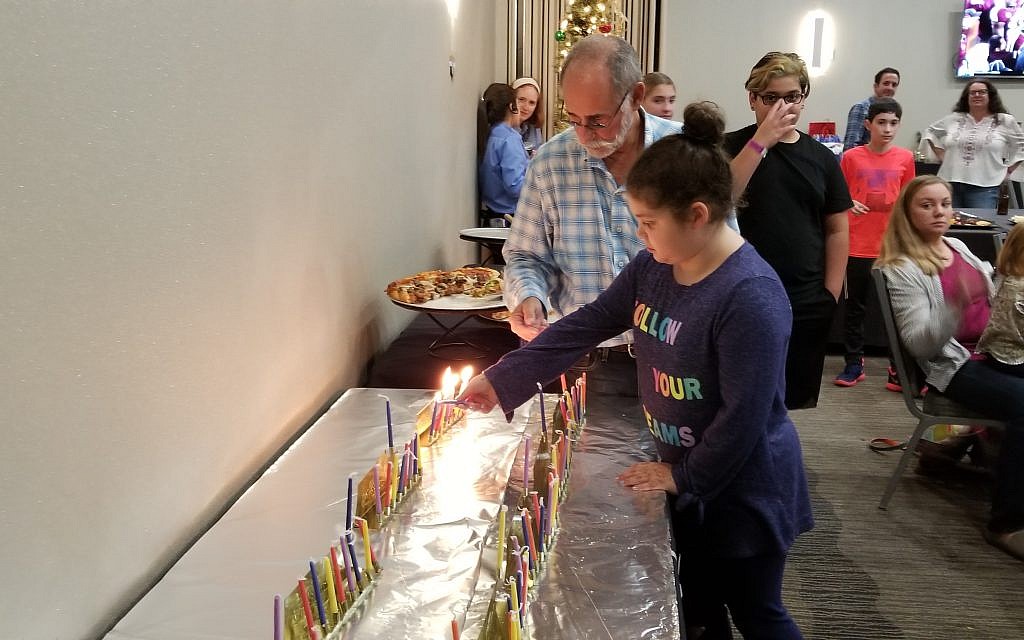

For a child, however, it was still a responsibility. So young Mississippi Jews breathed a sigh of relief when they would participate in regional youth groups such as the Southern Federation of Temple Youth, (SoFTY), the local branch of the Reform organization, NFTY. More significantly, young Mississippi Jews reveled in their summer experiences, year after year, at the Henry S. Jacobs Camp, part of the Reform movement, in Utica, Mississippi.

“Kids came from New Orleans and smaller towns, kids who had been in a minority were now in our element,” Jacobs said. “We learned how to live a Jewish life in camp, how to bench after the meals.”

At Camp Jacobs, which Abrams attended for 11 years as a camper and then as a counselor, “We no longer had to explain or justify anything. I started when I was in third grade. It was the first time I saw so many Jewish people. It really made me appreciate my Judaism and having a Jewish community and infrastructure. You don’t take it for granted,” added Abrams who met her husband, a native of Long Beach, Mississippi, at camp.

In fact, to this day, Atlantans from Mississippi speak of the strong bonds they have with the camp and the fellow campers who became their lifelong friends. “Camp Jacobs was the strongest part of our Jewish existence,” Levingston said, days before leaving on a ski trip with friends he met at camp. It was a camp friend who introduced him to the woman who would become his wife.

Levingston noted that it was one of his father’s peers, Macy B. Hart, who was the first director of Camp Jacobs in the 1960s and remained in that position for 30 years. That made his son, Micah, now living in Atlanta, “a staff brat until I was old enough to be a camper. People at camp expected me to know everything. They’d ask me, ‘What’s for dinner?’ I would answer, ‘I don’t know; I’m just 9 years old!’”

He said, “There were not a whole lot of Jews in Mississippi. If you were Reform and growing up in the ‘70s and ‘80s, you were recruited to go to Camp Jacobs. Camp was the cultural touchstone for my Jewish life. This is what made me Jewish. I was the only Jew in my class in elementary school. I’d bring stuff like a dreidel and matzo to show and tell.”

Hart, who hosts a summer camp podcast to keep the camp experience alive, explained the significance of the camp to him and other Jewish children from Mississippi. “I don’t think there are many times in life when you get to be yourself at that age.”

And the connections live on. This November, there will be a 50th reunion of Jacobs campers, said Hart, among whose counselors was Levingston.

“I grew up with Kevin (Levingston),” Friedman said. “Our families are friends.” She recalled Camp Jacobs as a “magical place.”

“We lived for the summers when we had all these Jewish people around us,” said Friedman, a fifth generation Mississippian. “My parents did everything they could to keep us Jewish,” she added, and camp was at the top of those priorities.

Not surprisingly, Pollack and Kashdan – nieces of Macy Hart – attended Camp Jacobs as well. “Every summer, all our cousins worked together at camp,” Pollack said. And, as her sister Stephanie noted, they had 14 first cousins. The extended Hart family includes 118 people who enjoyed a huge family reunion in October. The every-other-year family reunions were previously held at Camp Jacobs. Now they unite much closer to Atlanta, at Camp Ramah.

Indeed, it almost seems as if most Mississippi Jews are somehow related. “Deborah Jacobs’ aunt married one of my first cousins,” Kline said. His strongest memories growing up, however, don’t involve camp. During the Freedom Summer of 1964, when there was a strong move to register Southern blacks to vote, two Jewish civil rights workers came from the North and spoke at Kline’s synagogue. Two weeks later, along with a young black man, the Jewish youth were murdered, reportedly by members of the Ku Klux Klan.

“I was terrified the Klan would get my family,” Kline confessed. “I felt like I got a taste of what my mother went through,” he said about his mother, who was a Holocaust survivor.

Kogon’s most vivid memory occurred three years later, during the Six Day War. “I was walking downtown (in Meridien) and I was stopped at a light. A pickup truck pulls up next to me. It was a classic country pickup with the raccoon tail on the rearview mirror, and a rifle rack. It was quintessential redneck. The driver lowered the window and said, ‘We need to send that one-eyed general [Moshe Dayan], of yours to Vietnam.’ He knew I was Jewish and his image of Israel and me was impacted by the war. At that point I realized that the image of Jews in America was inexorably linked to Israel, whether I liked it or not. My connection to Israel came to me from that one encounter. It had such a profound effect on me. We were no longer victims.”

This ongoing series about Jewish life in small towns is sponsored by the Atlanta-based Jewish Community Legacy Project. Visit www.jclproject.org to learn more about the initiative to help such communities as they navigate the present and prepare for the future.

comments