New Book Recalls the Complicated History of Jews and Race

Atlanta Jews of Color Council is among the sponsors of a presentation by Professor Laura Leibman, author of “Once We Were Slaves".

Before there was Ancestor.com and MyHeritage.com, Blanche Moses, a Jewish heiress born in 1859 in New York, eagerly collected records to construct her family tree. But she hit a blank trying to research her maternal grandmother and great uncle, who she assumed were of Sephardic background. Using family heirlooms, however, Moses discovered that these ancestors had actually begun their lives as poor, Christian slaves in Barbados; their father was considered the “wealthiest Jew” on the island.

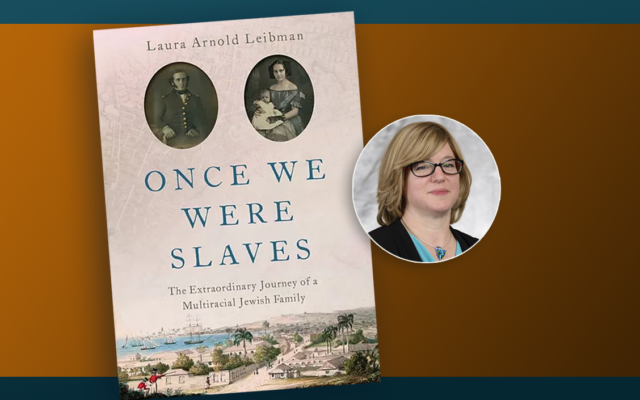

On Jan. 30, at 2 p.m., Laura Arnold Leibman, a professor of English and Humanities at Reed College in Portland, Ore., will bring the amazing story of this multiracial family to Atlantans, for free, via Zoom. Leibman will share her own exceptional story, about uncovering the history of the Moses family while researching and writing “Once We Were Slaves: The Extraordinary Journey of a Multi-Racial Jewish Family,” recently published by Oxford University Press. Sponsors of the presentation include the Jewish Genealogical Society of Georgia, a 30-year-old organization that joined the Breman Museum in 2003, and the Atlanta Jews of Color Council.

As Leibman explained, the story of the Moses family recalls the “largely forgotten population of mixed African and Jewish ancestry that constituted as much as 10 percent of the Jewish communities in which the older siblings lived” in the West Indies. And it underscores the fluidity of race, as well as the role of religion in racial shifts in the 19th century.

Victoria Raggs, executive director of The Atlanta Jews of Color Council, said the history of the Moses family is “relevant to today’s diversity equity advocacy. It gives context to the work that’s going on.” That’s why her organization has chosen to co-sponsor the program.

“We, as Jews, are collectively from the Middle East and Africa,” Raggs pointed out. “That surprises people who have the false notion that American Jews are entirely white and of European descent. Jews are everywhere and we should welcome all Jews. It’s important that we create communities with access to all Jews of color who have been traditionally excluded.” Although she said the white Jewish community is “making progress. There’s still some resistance. We can do better.”

Leibman told the AJT that what struck her as unique about this story was “that it allowed an entry point for people to learn how complicated and interesting early Jewish life was. Race worked really differently in the early 19th century. Race was a lot more fluid than we assumed.”

In the Dutch colony of Suriname, for example, Leibman said that “someone could be categorized as white if the parents were married,” even if one had owned the other as a slave. “That was different from Barbados, where you couldn’t change your race.”

Moses’s grandmother, Sarah Brandon Moses, who was born in 1798 and died in 1829, eventually married the son of a wealthy Jewish businessman, and both she and her children were categorized as white in the 1820 New York census. Her brother Isaac eventually joined her as a member of Philadelphia’s thriving Jewish community.

“People were racially ambiguous” in those days, Leibman explained. Racial definitions often depended on where a person lived, including in which U.S. state they resided.

“History such as this has the potential to help us realize the early history of the U.S. and across the Americas,” Leibman added. Like Moses, Leibman explores history and ancestry through objects, not just documents. “Objects hold emotional memories,” she said. “That’s what is wonderful about objects. It’s different from looking at records in Ancestry.com.”

Leibman said that she hopes this story will help her audience with “their own family history.” That’s partly why the Jewish Genealogical Society of Georgia (JGSG) wanted to bring Leibman to Atlanta.

“As a genealogist, I was astounded at Leibman’s research,” said Peggy Freedman, one of the founders of JGSG, and its coordinator. “We learn how New World Jews struggled with their identity in their times. I know Jews of color in Atlanta have a lot of interest in this topic, but anyone interested in history, race relations and genealogy” will be fascinated by Leibman’s research.

“It’s shocking material, but important for us to know where we came from, where we are and, hopefully, where we are going to,” Freedman said.

Raggs suggested that the Atlanta Jewish community “should be leaders in the nation,” given the rich history of civil rights here. But she said that “we’re falling behind what we can be.” What gives her hope is the younger generation, which, she says, is more sensitive to multi-culturalism

- Jan Jaben-Eilon

- News

- Local

- Laura Arnold Leibman

- Reed College

- Peggy Freedman

- Jewish Genealogical Society of Georgia

- Ancestor.com

- MyHeritage.com

- Blanche Moses

- family tree

- family heirlooms

- ancestors

- multi-racial family

- Zoom

- “Once We Were Slaves: The Extraordinary Journey of a Multi-Racial Jewish Family"

- mixed African and Jewish ancestry

- Jewish communities

- Barbados

- Christian slaves

- West Indies

- Suriname

- Sarah Brandon Moses

- family history

- New World Jews

- Victoria Raggs

- Atlanta Jews of Color Council

comments