Project Aims to Revive Small Town Jewish Life

Jewish Community Legacy Project sponsors first event of its kind to celebrate rich history in smaller town and cities in America.

After Perry Brickman’s parents married in Chattanooga in August of 1931, they went into business together. Despite the fact that it was one of the worst years of the Great Depression, they started the Dixie Coal Company in the small Tennessee city. His mother kept the books, his father was the salesman. Even in the dark years of the economic downturn, people needed coal to stay warm.

“My dad was a natural on the telephone,” Brickman remembered, “calling people to purchase their coal before the cold winter. He was a friend to many peddlers who filled up their wheelbarrows in the coal yard and sold the coal in the nearby neighborhood.”

Brickman, who was born in December of 1932, grew up in the neighborhood a few blocks from Chattanooga’s B’nai Zion synagogue. It was a small, closely knit Jewish community.

In many ways, it was not unlike Jewish life in small towns all over the South, It was similar to the Jewish experience in the European shtetls where many had first honed the social and commercial skills.

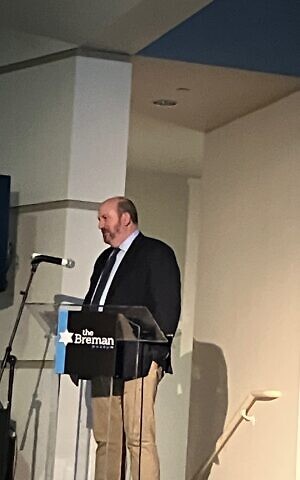

About 200 of those whose Jewish parents and grandparents were pioneers in the South and elsewhere got together earlier this month at a program jointly sponsored by the Atlanta Jewish Foundation and the Jewish Community Legacy Project. In the Sunday afternoon program at another sponsor, The Breman Museum, they heard their lifestyle in these often-isolated communities celebrated and lovingly recalled.

Emory University historian Eric Goldstein, who spoke at the event on Dec. 3, described the small-town experience of Jews in America as historically important.

“Even though only a minority ended up settling in small towns in the United States,” Goldstein said, “they were really carrying on the tradition and lifestyle that in some ways was more typical of the lifestyle that most of their ancestors in Europe had lived. So, anyone that tells you that, you know, New York is the only authentic Jewish experience and you’re somehow marginal if you come from a small town, just remind them that this was the history and background of most Jewish immigrants to the United States.”

There were about 45 communities from 17 states represented at the event. They grew up in places in the South like Waycross, Ga., and Kingbury. S.C., as well as towns like Caribou, Maine, and Topeka, Kan. Many of their early family members started out as peddlers going door to door in their small communities selling all sorts of household goods.

In Europe, life as a peddler was a dead-end job, but in America, in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, when many Jews left Europe for this country, humble beginnings carrying goods on a small wagon or even on your back could quickly lead to bigger and better things. The United States was still expanding, railroads were being built and new towns were blossoming, particularly in the South in the decades following the Civil War.

“Being a peddler was a job that could lead to great economic success and mobility,” according to Emory historian Goldstein. “And many of these peddlers could then end up very quickly opening a small shop in a small town and then expanding the business, ultimately having a very successful business.”

It happened in Hattiesburg, Miss., where Joel Adler’s grandfather and father became important small-town merchants and business leaders. They were part of a small, but thriving Jewish community, that grew increasingly prosperous particularly during World War II, when a large military base was opened just outside town.

But success in one generation led to burgeoning ambition in the next. Adler went off to the University of Maryland Dental School and instead of going back to Mississippi, he joined the Army.

“The army sent me to Germany, and I got my start doing oral surgery at a base there,” Adler said. “When I came back to the States, it helped me jump start my career and I opened a practice in Atlanta.”

It was a story, often repeated by those who gathered at the Breman for the program. Many who grew up in small towns, who could have had a comfortable life if they stayed there, sought their future in big cities like Atlanta.

The Jewish Community Legacy Project is attempting to partially reverse the trend by supporting synagogues in more than 200 small communities around the country, including an effort to reinvigorate small town Jewish life in six states in the South.

The recent event at The Breman is the first event of its kind in support of this program.

comments