Reflecting on the Plagues: Biblical, Medieval and Current

Rabbi Richard Baroff says our current pandemic is far less deadly than the plagues of the past.

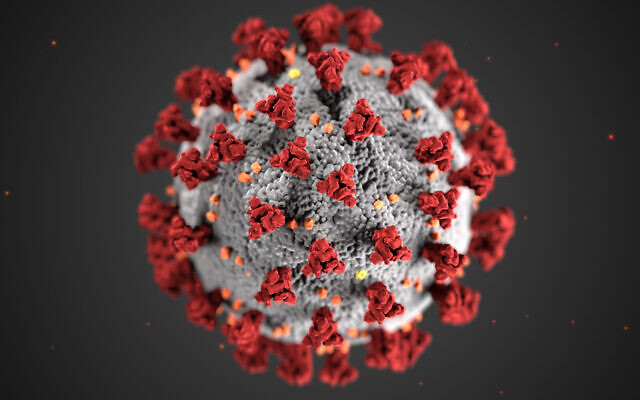

Perhaps no pandemic in human history has altered the world as quickly and dramatically as COVID-19. This is a function of our globalized community.

This is true even though there have been many plagues in human experience that have been more deadly.

The worst pandemic in history was undoubtedly the Black Death of the 1340s and ’50s. The Black Death devastated parts of Asia, Africa and especially Europe to a degree that is unimaginable. Many tens of millions of people died as a result of this form of the bubonic plague. At least a quarter, and perhaps as much as one half, of the people of Europe perished.

The social, cultural and economic effects were profound and long-lasting. Clearly the people had no idea what was causing the plague. Scientists have determined that this sickness is caused by bacteria carried by fleas which themselves infest rats. Rats were abundant throughout Eurasia, especially in the larger towns and cities. Large dark blotches would appear on the unfortunate victims, and so the term Black Death was used for this terrible curse, which came to be known as the Plague.

The Black Death marked not only the most dreaded time in the Middle Ages generally, but for Jews, in particular. At the time, Germany was not a political entity but a cultural and linguistic region. There started a rumor that the Jews had poisoned the wells, and thus the Jews were the epidemic’s cause.

It was noted that Jews were somewhat less likely to die in the plague than their Christian neighbors. If this were indeed true, then the reason probably had to do with halachah: Jews followed strict rules regarding washing and food preparation.

Of course many Jews succumbed to the bubonic plague as well as the gentile population.

In the moral panic that ensued, hundreds of Jewish communities in Germany were completely wiped off the map. Some entire Jewish communities were burned alive. The number of victims of these pogroms remain unknown.

There were Christian leaders who tried to stop the vengeful mobs. Most notable in this regard was the pope himself, a Frenchman named Clement VI. He maintained the Jews’ innocence and ordered Catholic priests to protect the Jews whenever and wherever possible.

Others groups were also targeted to a lesser degree in the hysteria, including other foreigners and lepers, but the Jews were, as was so often the case, singled out for murder. Thousands were killed in Strasbourg, Speyer, Mainz and Cologne. There were even attacks outside of Germany in Switzerland, Flanders and Spain.

Soon these Yiddish-speaking Jews of Central Europe who had already suffered expulsions, defamation and the Crusade massacres, would be welcomed in Eastern Europe – in Poland, in particular. There, in the second half of the 14th century and for centuries afterward, the Yiddish-speaking Jews would develop a flourishing civilization. Jewish life in Poland-Lithuania-Ukraine would define much of Yiddish culture, and mold so much of the Ashkenazi experience.

Certainly a prominent feature of the Passover seder is the recitation, in the haggadah, of the Ten Plagues visited upon the Egyptians as a result of the Pharaoh’s recalcitrance.

Some of these plagues we today would recognize as pandemics, others would not be. Some of the plagues would appear to be clearly supernatural: dam/blood, hoshech/darkness, makkat bechorot/slaying of the first born.

Others are animal infestations: tzefardea/frogs, kinnim/lice, arov/wild beasts, arbeh/locusts. Barad/hail was a meteorological threat and stands on its own. Two plagues represent true illnesses: Dever was a pandemic affecting cattle; shechin /boils was the only disease attacking humans directly.

It is worth noting that the Hebrew term for the Ten Plagues, Eser Makkot, really means the Ten Blows delivered by G-d. In Hebrew, magefah means plague in the medical sense. Nevertheless, in this age of coronavirus, when our second Pesach in two years will be altered by social distancing from family and friends, the translation Ten Plagues will have a special resonance.

Ignorance, fear and panic gripped Europe in 1348 to 1350. This led to the scapegoating and murder of so many Jews and the destruction of hundreds of communities.

In 2020 to 2021 we have the benefits of coordinated scientific communities that have moved very quickly by historical standards to solve the global crisis.

Israel is helping to lead the way in vaccinations; the rest of the world is looking at how the Jewish state progresses in terms of herd immunity.

We all look forward to next year when hopefully we can have a normal seder with family once more. In the meantime, we ask the Holy One for a bit more savlanut, a bit more patience, to get us through what is, we pray, the last chapter of this terrible virus.

Have a Hag Samayach in spite of it all.

Rabbi Richard Baroff is president of Guardians of the Torah in Roswell.

comments