The Jewish Marilyn Monroe – Gone but Not Forgotten

Learn a few of the lesser-known facts about one of Hollywood's icons, including her journey to Judaism.

In the late hours of Aug. 5, 1962, Marilyn Monroe took a handful of Nembutal barbiturates, washed it down with a glass of Piper-Heidsieck champagne and died in her sleep. Just over 57 years later, the icon of mid-century glamour is still remembered for the wit, beauty and almost effortless sexuality she brought to a string of Hollywood hits in which she was often cast as the perennial dumb blonde.

But often overlooked in an appraisal of her extraordinary career, is the role that Judaism and the American Jewish community played in her life. She converted to Judaism shortly before her marriage in 1956 to Arthur Miller, the Jewish playwright, Pulitzer Prize winner and dramatic genius. He was her third husband.

Monroe once told Paula Strasberg, her drama coach at the time, that she felt a special kinship with her newfound faith.

“I can identify with the Jews,” she said. “Everybody’s out to get them, no matter what they do, like me.”

On the front door of the home where she died, she had affixed a mezuzah with its tiny parchment scroll of sacred Jewish writings. She still had the prayer book with her personal notes written in its pages, a gift from Miller that had once belonged to the Brooklyn synagogue where he had had his bar mitzvah. On her mantle she kept a bronze menorah, which played “Hatikvah,” the national anthem of the State of Israel. It was a present from Miller’s Yiddish-speaking mother.

Rabbi Robert Goldburg had worked with her during her conversion and provided her with a number of Jewish historical and religious works to study. About three weeks after her death, he wrote of his impressions of her at the time.

“She was aware of the great character that the Jewish people had produced. … She was impressed by the rationalism of Judaism — its ethical and prophetic ideals and its close family life.”

For Monroe, who had been born to a single mother with severe psychological illness, had never known her father and was raised in a series of foster homes, the promise of a warm family life was undoubtedly an important part of what attracted her to Jewish life.

When she rebelled against the exploitation of the Hollywood studio system, broke her contract with 20th Century Fox and fled Hollywood in 1954 for a new life in New York, it was at the urging of Milton Greene, a popular Jewish photographer with whom she founded Marilyn Monroe Productions. For a while she lived with Greene and his wife and helped take care of their year-old son.

Even before the move she lived and worked in what was largely a Jewish world. In Hollywood her agent and publicist and an early drama coach and mentor were all Jewish.

She owed her early success, in part, to personal relationships with the powerful Jewish studio executive Joseph Schenck and the important talent agent Johnny Hyde, who had originally emigrated from the Jewish Ukraine. Her three psychiatrists were Jewish as well as many of her doctors. One of her closest journalistic confidants was the newspaper columnist Sidney Skolsky.

But all that accelerated when she moved to New York and enrolled in Lee and Paula Strasberg’s Actors Studio, which had trained such stars as Marlon Brando, James Dean and Paul Newman. She quickly fell in with their circle of friends, who made up the theatrical and literary elite of Jewish New York. She volunteered to be the star attraction at a United Jewish Appeal dinner.

The poet Norman Rosten and his wife and children were close friends. She was a regular at a summer of brunches and picnics and cookouts with the Strasbergs in Ocean Beach on Fire Island. She frequently dug into what Paula Strasberg called her “Jewish icebox” there, with its salamis from Zabar’s on New York’s Upper West Side and the honey cakes and fancy European pastries from some of the bakeries started in New York by refugees from Nazi persecution.

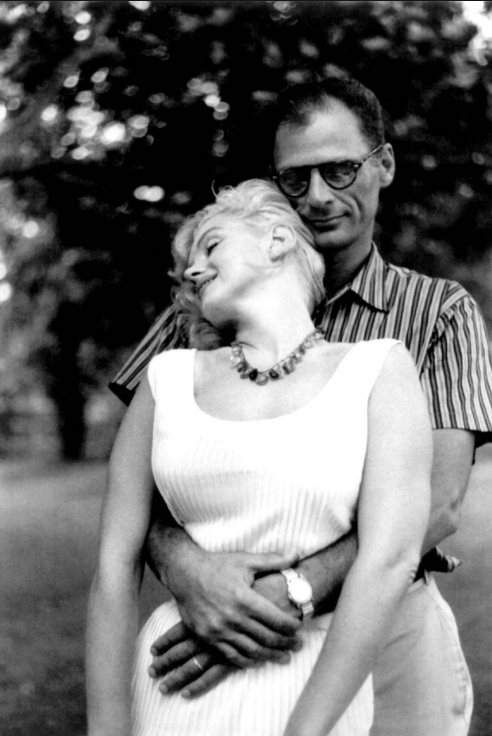

It was, in the words of one Monroe biographer, “a year of joy,” made even more joyful by a newfound romance with Miller, whose quiet, serious personality she found strangely irresistible. She first met him five years earlier, when she was not yet a star. She told a close friend about the initial meeting, “It was like running into a tree! You know, like a cool drink when you’ve got a fever.”

After renewing their friendship in New York, they went for long bike rides in far off corners of Brooklyn, away from the press, and for a while, worked hard to keep their relationship a secret.

But by the early summer of 1956, Miller had divorced his wife of 15 years, said goodbye to his two children and married Monroe, first in a civil ceremony and then on July 1, under the chuppah at the home of his literary agent.

Gloria Steinem, the Jewish American essayist and feminist, wrote a perceptive analysis about the relationship and Monroe’s decision just before their marriage to convert to Judaism.

“Miller himself was not religious, but she wanted to be part of his family’s tradition. ‘I’ll cook noodles like your mother,’ she told him on their wedding day. She was optimistic this marriage would work. On the back of a wedding photograph, she wrote ‘Hope, Hope, Hope.’”

Her public commitment to Judaism in the mid-50s was just one of the signs that Jews were winning new acceptance in America after the end of World War II and of the changes that the war had brought.

American Jews, who had been educated under the GI Bill, were moving up in the world. Anti-Semitic barriers were falling in housing and education, the professions of law and medicine were becoming more open to Jews, and college quotas were, for the most part, ended.

So many Jews were moving to new homes in the suburbs that Conservative Judaism was forced to drop its ban on driving to the synagogue on Shabbat. The executive director of the Anti-Defamation League, Benjamin Epstein, called the two decades after the war a “golden age,” in which American Jews “achieved a greater degree of economic and political security and a broader social acceptance than had been known by any Jewish community since the (ancient) Dispersion.”

So when Eddie Fisher, the Jewish son of Russian immigrants, married a cute blonde shiksa from El Paso, Debbie Reynolds, in the mid-50s, and Miller married Monroe, some saw the marriages not so much as a threat to the Jewish future as a sign that Jews were finding their place in America.

During that time, the Conservative movement opened more than 100 new synagogues annually. Reform congregations in 1955 had more than 255,000 members, up from just 59,000 in 1940. By the late 1950s, 60 percent of American Jewry belonged to synagogues. It was the last time synagogue membership in America would be made up of more than half of the country’s Jews.

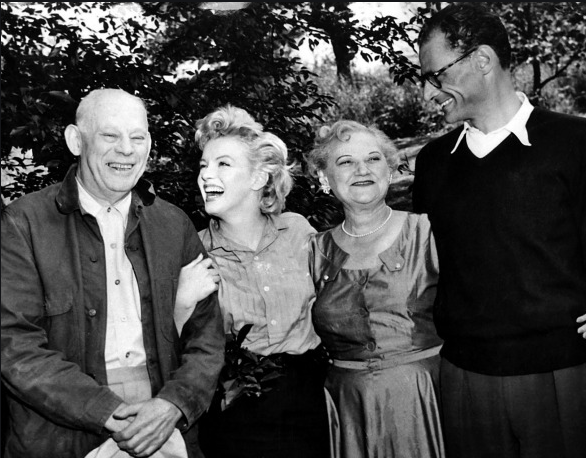

After the marriage Modern Screen magazine promoted on its cover a story, “Marilyn Enters A Jewish Family,” which included a photo spread of Marilyn and her new in-laws.

Two years later, to make the point even more strongly, Elizabeth Taylor converted to Judaism to honor the memory of her Jewish husband Mike Todd, who had died suddenly in a plane crash.

Despite Monroe’s initial hopes for the marriage, the five years she spent with Miller were difficult ones. Her dreams of a family faded after an ectopic pregnancy and two miscarriages.

Even though she achieved considerable success in one of the great screen comedies, “Some Like It Hot” in 1959, Monroe was never able to overcome the professional insecurities and psychological problems that led to a serious addiction to prescription medications and alcohol, and ultimately to her sudden death.

But although she’s been gone these many years, she is not forgotten. Time has treated the memory of Monroe with kindness. Her estate, most of which she left to the Strasberg family, has consistently earned tens of millions of dollars over the more than 50 years since her death. Last year her name and image made $17 million and she ranked No. 8 on the Forbes list of the highest-earning celebrities who are no longer living.

As for that prayer book that Arthur Miller took from his Brooklyn synagogue and Monroe kept to her dying day, it sold at auction last year for $18,000.

Bob Bahr will be teaching “Anything For A Laugh – American Comedy and the American Jewish Soul” at The Temple this fall.

comments