Withdrawal from Afghanistan: Lessons for Israel

Following the withdrawal from Afghanistan, Ken Stein believes the U.S. should cultivate Middle Eastern friends.

In August 2021, the U.S. withdrew its military from Afghanistan, ending America’s longest war. Necessarily, twenty years earlier, the U.S. retaliated against Muslim terrorists and their sanctuaries in Afghanistan because America was brutally attacked on 9/11. We killed Bin Laden and invested heavily in trying to remake Afghanistan into a country where western values might matter. We and our allies spent exorbitant amounts in human treasure and more than a trillion dollars during our Afghan engagement. What lessons to take from this experience?

Correctly, we needed to prevent another 9/11 on our doorsteps. We still have that imperative. With American withdrawal, the jails in Afghanistan are being opened and unpoliced borders will allow a flow of additional jihadists to assemble and execute more attacks on the U.S. and its allies.

U.S. presidents and their administrations naively believed we could grow Jeffersonian democracy and nurture civic responsibility in a state where tribal, family, ethnic and sectarian identities still magnetize societal cohesion. President Bush wanted regime change. President Obama refused to embrace publicly the reality of Islamic extremism. Forced domestic changes from foreign countries are doomed to failure.

In February 2020, President Trump signed a “deal” with the Taliban. According to two of his national security advisers, John Bolton and H.R. McMaster, Trump signed a “surrender” agreement with the Taliban, legitimizing their rule. When Trump left office, he left President Biden with fewer than 5,000 U.S. troops remaining in Afghanistan. Biden promised to be out of Afghanistan by September.

Both presidents made unnecessary public promises that locked each into definitive policy actions in specific time frames. Why do presidents have to make significant policy intentions public? How needless was President Obama’s 2013 public announcement that the U.S. was not interested in regime change in Tehran?

I would wager that when the Iranian clerical leadership heard his remarks, they found whatever appropriate beverages were available, and collectively said, “L’Chaim!”

Each presidential administration failed to realize that for Afghan political culture, as for other Middle Eastern states and political insurgencies, success is determined by staying power. Resilience is often measured by buying time for some undefined period until the adversary may be worn down into weary submission. Sometimes the objective is to negotiate, that is, not to achieve an outcome but to gain legitimacy. To one degree or other, Iran, Hezbollah, Hamas, elements within the Palestinian Authority (PA), and the Assad family in Syria all subscribe to the premise of ideological staying power. Every match for them can go into limitless extra-innings, never bounded by clock or calendar, or finalized by a last at-bat. It is the last country or entity standing.

Lessons for Israel’s Presence in the West Bank

There are lessons for Israel to learn from America’s withdrawal from Afghanistan. In its own history, when Israel withdrew unilaterally from both Lebanon in 2000 and from the Gaza Strip in 2006, it handed security duties over to the UN and to the PA, respectively. More than 8500 Israelis were displaced from the Gaza Strip and the West Bank. In both cases, those withdrawals did not work out well for Israel. Hamas brutally removed the PA from control of the Gaza Strip in 2007, leaving a hostile Palestinian insurgency on Israel’s southern border.

Israel cannot withdraw unilaterally, if at all, from the West Bank or from the West Bank’s borders, leaving it in the hands of another political entity. The Israeli columnist Ben-Dror Yemini made a very strong case that the fall of Kabul is a warning sign for Israel. Jerusalem must control those boundaries while maintaining active intelligence operations there.

Second, the Afghan army’s complete or partial disintegration in the face of a determined group of jihadists has implications for Israel. Highly influential Arab and Palestinian analysts proclaim the PA is inept, dysfunctional, and corrupt; they roundly criticize the PLO for its blatant failure to move from a liberation movement to building effective state institutions. The Palestinian Authority Security Services in the West Bank are a police force trained to handle counterterrorism; they are not an army trained to quash a rebellion that might emerge from a dedicated group of jihadists bent on overthrowing a weak PA.

For a decade, our CIE staff has chronicled statements and plans made on behalf of a two-state solution. No matter how dedicated advocates of a two-state solution are, their incessant prompting should not determine what happens on the ground. Every Israeli prime minister since June 1967 has understood the geographic realities of the West Bank, sandwiched between Israel and Jordan. Each prime minister has postponed the devolution of any foreign sovereignty for the West Bank, allowing for implementation of confidence-building measures to evolve between Israel and the Palestinians. Israel can get out of the lives of the Palestinians without getting out completely from the West Bank.

At present, the PA and the PLO are not viable institutions that represent the interests of the Palestinian people. In fact, many Palestinians still believe in the Hamas ideology that Israel’s very existence, and not merely its presence in the West Bank, is the ‘occupation.’ Yasser Arafat, former head of the PLO, recognized Israel in 1993 because he wanted and needed international legitimacy from the U.S. when he was openly challenged for command of the Palestinian leadership. Arafat said as much in a private meeting in Washington, D.C., with President and Mrs. Carter and me the night before he signed the Oslo Accords. In 2020, the Taliban sought similar legitimacy from the Trump administration. Israeli-Palestinian negotiations that begin before the PA is thoroughly reformed will only entrench a corrupt Palestinian leadership and doom any long-lasting agreement.

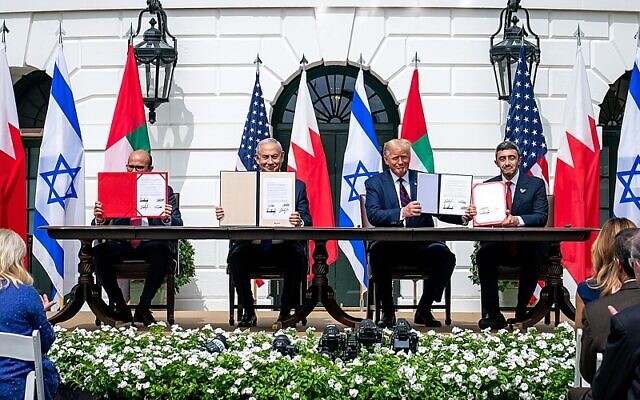

Building on the Abraham Accords

A year ago, the Abraham Accords were signed. During the previous decade, the UAE, Bahrain, and Israel played nicely. Trust formed between people and the elites. It was top-down and bottom-up diplomacy. Common strategic and economic national interests were and are shared; geographically proximate Iranian toxicity remains a common threat to be stifled.

In case anyone forgot that the Palestinians had major issues with Israel, Hamas fired rockets into Israel in May, sending Israelis into shelters and into a justifiable military retaliation. The Abraham Accords did not break. They remained alive as a strategic scaffolding to be built upon. By the end of 2020, agreements with Morocco and the Sudan followed those with the UAE and Bahrain. Relationships were not based on ideology but on enhancing mutual strategic interests. Every country that made peace with Israel also received something from American coffers: economic assistance, weapons, recognition or restoration of rights and guarantees. The U.S. footprint need not be physical; it can be substantial if consistently supportive of common objectives. We should evolve further an effective if not loose alliance system of Middle Eastern friends.

Professor Ken Stein is the founding president of the Atlanta-based Center for Israel Education.

- Opinion

- Community

- Kenneth Stein

- Center for Israel education

- President Barack Obama

- George W. Bush

- President Donald Trump

- President Joe Biden

- Bin Laden

- September 11

- President Jimmy Carter

- Rosalynn Carter

- Taliban

- Muslim terrorists

- Afghanistan

- American withdrawal

- Jihadists

- John Bolton

- H.R. McMaster

- foreign countries

- Tehran

- Promises

- Iran

- Middle East

- Israel

- Lebanon

- Gaza Strip

- West Bank

- United Nations

- Palestinian

- Bahrain

- Hezbollah

- hamas

- Palestinian Authority (PA)

- Assad family

- Syria

- Washington D.C.

- Oslo Accords

- United Arab Emirates

- Morocco

- Sudan

- Ben-Dror Yemini

- Kabul

- Jerusalem

- Army

- police force

- Counterterrorism

- Jordan

- Yasser Arafat

- Abraham Accords

comments