The Multi-Faceted Yizkor Service

History, facts and lore about the Jewish memorial prayer for the dead.

Chana Shapiro is an educator, writer, editor and illustrator whose work has appeared in journals, newspapers and magazines. She is a regular contributor to the AJT.

We are all familiar with the mad rush to synagogue by many on Yom Kippur to be at services in time for the recitation of Yizkor. The name of the service comes from the Hebrew word zachor, to remember. As such, Yizkor is the memorial prayer for members of one’s immediate family and others who are no longer living.

I consulted a few books by rabbinic authorities I have in my possession to learn more about the service.

For many modern Jews, some who do not attend synagogue at other times, the most meaningful aspect of Yom Kippur is the Yizkor service, the purpose of which is described by Rabbi Chaim Binyamin Goldberg in “Mourning in Halachah” as “the elevation of the souls of the departed.” Some congregations include prayers for those who don’t have any descendants, fallen Israeli soldiers and martyrs. Yizkor is followed by “El Malei Rachamim” (merciful Father) prayer.

According to Rabbi Goldberg, those with both living parents have no obligation to recite Yizkor, and these non-mourners usually leave the sanctuary during the Yizkor service. Rabbi Alfred J. Kolach in “The Jewish Book of Why” suggests that some people believe it would “tempt fate” to prematurely recite or be present during the Yizkor service. Some synagogues wish to eliminate distraction or pain (even jealousy) for grieving mourners from praying amid people who are not mourners.

Yizkor was not part of the original Yom Kippur service. In “The Jewish Book of Why,” Kolach notes that in ancient times the Maccabees attempted to establish a prayer for their fallen companions, but that practice did not catch on. Later, Rabbi Simcha ben Samuel of Vitry, a pupil of the French Medieval commentator Rashi, included a Yizkor service in his 11th century holy day prayer book.

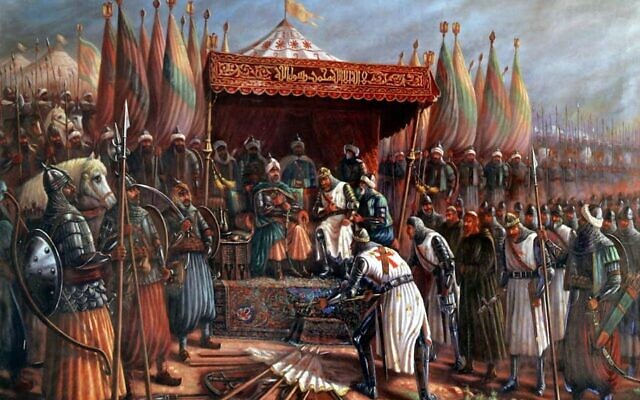

It is likely that Yizkor became a formal part of the Yom Kippur service

during the bloody Christian Crusades of the 11th century, Rabbi Kolach explains. Thousands of Jews were slaughtered as the Crusaders made their way through the “Holy Land,” and communities throughout the region responded to the enormous tragedy by creating the memorial prayer, expressing the hope that the deceased would intervene with the Almighty to bring an end to Jewish suffering, Kolach said.

At first, Yizkor was only recited on Yom Kippur, but over time it was also included in the synagogue services of the Jewish festivals of Passover, Shavuot and Sukkot.

Historically, there has been scholarly opposition to including Yizkor in the Yom Kippur and festival services, specifically against praying for the dead on Jewish holy days, Rabbi Kolach wrote. In addition, the idea of divine intervention by the deceased to positively affect the lives of the living was challenged. The donation of charity in memory of one’s relatives for this purpose (rather than relying on one’s own good deeds) was contested, he said. Yet, the Yizkor service spread, with charity as an integral part of the observance.

Sephardic Jews do not include the communal Ashkenazi Yizkor prayer in their holy day services, according to Rabbi Yehuda Boroosan of Congregation Netzach Israel in Atlanta. It is their custom for individuals to recite “Hashkabah,” a memorial prayer during the first year of mourning and on the Shabbat closest to the deceased’s date of death. The 16th century Sephardic author of the Shulchan Aruch (the Code of Jewish Law) Joseph Caro espoused giving charity for the dead. In many Sephardic synagogues a “Hashkabah” for a long list of deceased members is read in conjunction with the Kol Nidre evening service, Rabbi Boroosan said. Some Sepharadim also have the custom of lighting a candle.

Ashkenazic Jews traditionally light a 24-hour Yizkor memorial candle at home, in the evening just before the onset of Yom Kippur. A single candle may honor more than one person. However, many people light a candle for each parent and other members of their family, Rabbi Kolach stated. A candle with a flame, representing the relationship between body and soul, is preferable to an electric one

A public physical aspect of remembrance is the Yizkor tablet, a plaque of remembrance displayed in Jewish places of worship, as noted in “Understanding Judaism: The Basic of Deed and Creed,” by Rabbi Benjamin Blech. These plaques bear the names of people who have passed away, with the dates of their birth and death. The lights beside all of the names are illuminated on days when Yizkor is recited, uniting all mourners as they join together in prayer.

comments