Researchers Entering New Era for Alzheimer’s Research

New drugs are getting FDA approval and Israeli doctors report what they say could be a major breakthrough in understanding the disease.

Israeli medical researchers have come up with what they believe may be a breakthrough in the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. The illness, which affects an estimated 40 million persons around the world, including six million in the United States, is the leading cause of dementia in this country.

The disease, which is difficult to treat, is the source of considerable anxiety and stress among families and caregivers who feel they are helpless during the relentless advance of the illness.

The Israeli scientists, who emphasize they are only in the preclinical trial, have developed a treatment that interferes with the development of a protein in the brain called PTEN, which up to now was thought to be involved only in the development of cancer. But the scientists working at the Ben Gurion University of the Negev found high levels of PTEN interacting with another protein called PSD-95 that can cause breakdowns in communication along the many nerve cells in the brain. The result is deterioration or atrophy in key areas that are involved in memory.

The director of the University of the Negev’s Molecular Cognition Lab, Dr. Shira Knafo, believes that the way the two proteins interact erodes the passageways that produce memory.

“When there’s too much of the PTEN protein, it becomes toxic to the synapses. What we saw is that in Alzheimer’s disease, the (surplus) PTEN enters the synapses and causes them to be much weaker. When they become weak, they can’t pass information that well, and then you see loss of brain function and memory because the synapses are considered to be the place of information storage.”

The laboratory developed a peptide, which is one of the fundamental substances in the production of proteins, to prevent PTEN from degrading memory.

Whether the breakthrough in the understanding of how various proteins function will ultimately produce an effective therapy for the treatment of Alzheimer’s will depend on the results of peptide trials, which are taken orally in the United Kingdom, China, Hong Kong, and Israel.

AstraZenica, the European biomedical company has also begun testing a medication called Saracatinab, which, like the Israel research, aims to allow synapses to communicate better. Research in mice has shown the drug to reverse some memory loss and testing has been expanded to human trials.

In the United States, there have also been some promising developments over the last several years to develop treatments that can slow the progression of the disease. In May, the American drug manufacturer Eli Lilly and Company announced that results of stage III trials for its new Alzheimer medication, Donanemab, showed that the drug, in patients that were in the early stages of the disease, could slow its progression by as much as 35 percent.

The drug is a monoclonal antibody drug, which means it mimics the behavior of proteins in the body that fight off infections or other disorders. The drug, which is expected to be submitted for approval by the FDA next year, joins two other monoclonal antibody treatments that have received federal approval. All three of the drugs are aimed at preventing or even removing what are called amyloid plaques, or clumps of the protein that come together in the brain and are believed to disrupt memory functioning.

The trials for Donanemab showed that patients also had a 40 percent lower risk of moving from mild cognitive impairment to more serious memory loss. Similar results for memory loss were reported for the drug Lequembi, which received final FDA approval in July. The two therapies join a third treatment, Aduheim, which was announced last year.

The news of the three treatments has been greeted with cautious optimism by researchers and medical brain specialists, including a number at Emory University’s Brain Health Center, who have been quick to point out that the drugs are expensive, not always easy to administer, require careful and expensive monitoring, and can cause abnormal swelling and bleeding in the brain and can even result in death.

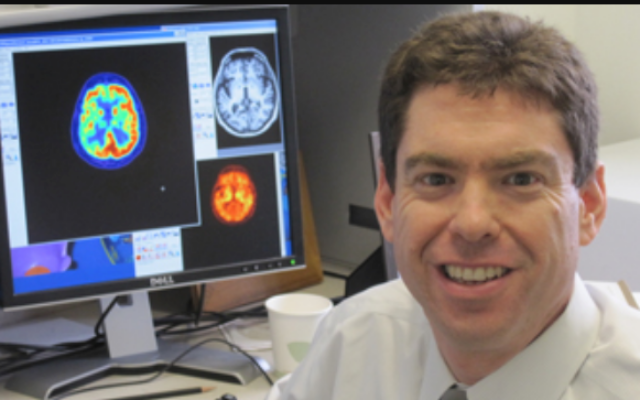

Because they seem to only be effective in cases of Alzheimer’s disease that are considered to be at an early stage, they are not useful for those who have more serious symptoms. Still, Dr. Gil Rabinovici, director of the University of California San Francisco Alzheimer Disease Research Center, wrote in an editorial of the Journal of the American Medical Association this summer that the results of the latest monoclonal are “just the opening chapter in a new era of molecular therapies for Alzheimer’s disease and related neurodegenerative disorders.”

But he went on to write that the drug’s potentially serious side effects should encourage researchers to “aim higher in developing more impactful and safer treatments.”

- Alzheimer’s diseas

- News

- Health and Wellness

- Bob Bahr

- PTEN

- Ben-Gurion University of the Negev

- PSD-95

- Molecular Cognition Lab

- Dr. Shira Knafo

- AstraZenica

- Saracatinab

- Eli Lilly and Company

- Donanemab

- monoclonal antibody drug

- Lequembi

- Emory University’s Brain Health Center

- Dr. Gil Rabinovici

- University of California San Francisco Alzheimer Disease Research Center

- American Medical Associatio

comments