Baseball Legend Was A High Holy Days Hero

His decision to observe the High Holy Days during the 1934 American League playoffs still has a profound effect on Jewish Americans.

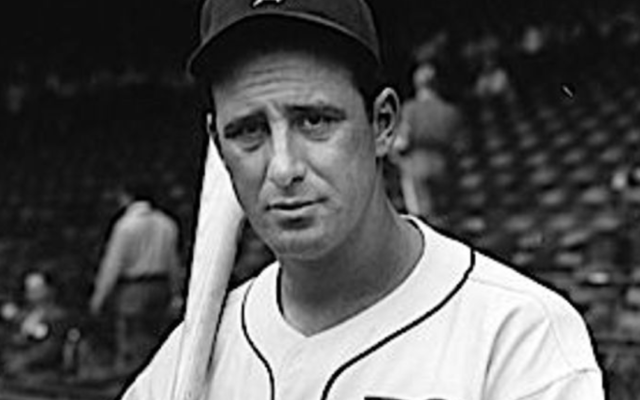

On Yom Kippur, the 10th of Tishrei, 5696, which coincided with September 18, 1934, Hank Greenberg, the 23-year-old first baseman for the Detroit Tigers made American Jewish sports history. On that day, the hard-hitting 6-foot 4-inch Greenberg — who was also known as Hammerin’ Hank, the Hebrew Hammer — didn’t play baseball.

Even though the Tigers were battling the New York Yankees for their first American League pennant in 25 years, Greenberg went to services on the Day of Atonement at Congregation Shaare Zedek, Detroit’s largest Conservative synagogue.

He had quietly observed Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur in 1933, his rookie season.

In 1934, on the day before Rosh Hashanah, the local paper had wished him a Happy New Year in Hebrew on its front page, but Greenberg, whose parents were observant Jews from Romania, agonized over playing that day.

He may have been influenced by a local rabbi’s public decision that Jewish law encouraged joyful experiences on the holiday, and thus he had permission to play ball.

Nonetheless, his decision to play on Rosh Hashanah during the playoffs is the stuff of Jewish sports legends. After a morning visit to his synagogue, he hit two home runs during that game, including a booming shot over the left-center field fence in Detroit during the 9th inning that clinched a 2-1 victory for the Tigers.

Yet, at a time when many prominent Americans were beginning to admire Adolf Hitler and his campaign against the Jews in Germany, he had to endure endless insults. When Greenberg told one of his biographers about what it was like playing baseball in the 1930s, he didn’t mince words.

“How the hell could you get up to home plate every day and have some SOB call you a Jew bastard and a kike and a sheenie and get on your ass without feeling the pressure? If the ballplayers weren’t doing it, the fans were. I used to get frustrated as hell. Sometimes I wanted to go up in the stands and beat the s—t out of them.”

One of the nation’s foremost collectors of Jewish baseball memorabilia, Dr. Seymore Stoll, points out that, for Greenberg at the time, anti-Semitism was an integral part of the Great American Pastime.

“He had to endure a lot of anti-Semitism in Detroit. Henry Ford, who had his Ford Motor Company there, was no friend of the Jews. And, of course, they had the anti-Semitic Catholic priest, Father Charles Coughlin, who had a church in the Detroit suburbs. He had 30 million listeners to his nationally broadcast CBS radio show every weekend, saying how evil the Jews are. So, it wasn’t easy for him even as a superstar,” Stoll said.

Despite a long history of prejudice, Jews have been an integral part of baseball’s history. Stoll, the baseball historian, has counted 191 Jewish baseball players since 1867, when Lipman Pike became one of the first stars of professional baseball.

In 2014, the National Museum of American Jewish History organized a traveling exhibit about the Jewish love of baseball titled “Chasing Dreams – Baseball and Becoming American.” The exhibit, which featured 130 historical objects, including Hank Greenberg’s 1935 Most Valuable Player award, was hosted by the William Breman Jewish Heritage Museum in Atlanta.

American Jews and the national game are so intertwined that the exhibit even included a quote by Rabbi Solomon Schechter from the early 20th century. The famed scholar and one of the founders of the Conservative movement in America, had one critical requirement for new rabbis.

“Unless you can play baseball, you can never get to be a rabbi in America.”

Thirty-one years after Greenberg’s historic stand, Sandy Koufax, the famed pitcher for the Los Angeles Dodgers gained the admiration of Jewish Americans when he sat out the first game of the 1965 World Series on Yom Kippur. In the years since, a growing number of Jewish players have made their own peace with the holidays.

A few days after the Day of Atonement in 1934, Greenberg’s hometown newspaper, the Detroit Free Press, ran a poem titled “Speaking of Greenberg” by the popular writer Edgar Guest, who hailed Greenberg’s decision. It read in part:

“Came Yom Kippur — holy fast day worldwide over to the Jew —

And Hank Greenberg to his teaching and the old tradition true

Spent the day among his people and he didn’t come to play.

Said Murphy to Mulrooney, “We shall lose the game today!”

We shall miss him on the infield and shall miss him at the bat,

But he’s true to his religion — and I honor him for that!

- Bob Bahr

- Local

- Baseball

- High Holidays

- rosh hashanah

- Yom Kippur

- William Breman Jewish Heritage Museum

- Hank Greenberg

- Edgar Guest

- Solomon Schechter

- Dr. Seymore Stoll

- Henry Ford

- Father Charles Coughlin

- Lipman Pike

- Sandy Koufax

- Jews and baseball

- Los Angeles Dodgers

- Detroit Free Press

- Detroit Tigers

- New York Yankees

- 1934 American League playoffs

- Hammerin’ Hank

- The Hebrew Hammer

- American League

- Jewish players

- 1965 World Series

- Congregation Shaare Zedek

- Romania

- ballplayers

- Ford Motor Company

- Day of Atonement

- Tishrei

- Germany

- Anti-Semitism

- Great American Pastime

- CBS Radio

- National Museum of American Jewish History

- Sports

comments