Thank You, But Leave My Name Out Of It

Dave’s work and condition provide him with a reason to learn more about the Mi Sheberach prayer.

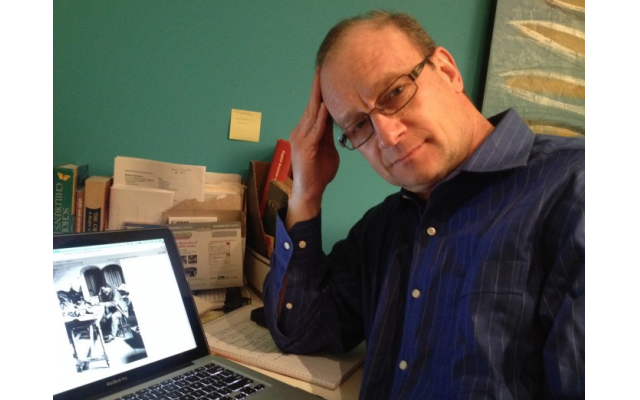

Dave Schechter is a veteran journalist whose career includes writing and producing reports from Israel and elsewhere in the Middle East.

I was explaining to a friend my reluctance – even after writing about my cancer diagnosis in this column – to have my name said aloud as part of a Mi Sheberach (“May the one who blesses”) list.

Perhaps it is my lack of religiosity, or my skepticism about the efficacy of prayer – the available research is a mixed bag of yes, no, and maybe – or feeling that there are others in greater need of such invocations.

Or, maybe, I have an unrealistic desire to feel that I can maintain a modicum of control over the situation. [For the record, I’m receiving the recommended treatments and adjusting to being a member of that club no one wants to join.]

When I hear a friend’s name on a Mi Sheberach list, I naturally am curious about their condition. But shouldn’t it be left to the person who is ill to decide what and whom to tell, rather than my seeking out that information? Would I not be engaging in lashon hora (evil speech) or rechilut (gossiping) by inquiring with a mutual friend, possibly putting that person in an uncomfortable position?

Leviticus 19:16 says: “You shall not go up and down as a slanderer among your people.” Some sources included the substitution of “talebearer” for “slanderer.”

This column, suggested by the above-mentioned friend, is the latest example of how my work provides me the opportunity to learn more about aspects of Judaism and Jewish life. At the outset, I knew that the Mi Sheberach was a prayer for people who are ill or recovering from an accident, and that the rendition by the late Jewish folksinger Debbie Friedman is popular in many non-Orthodox congregations.

I did not know that the Mi Sheberach has multiple applications and that there is no uniformity in how the prayer is presented within and across the various Jewish movements.

The Mi Sheberach, which traditionally is said during the Torah service, dates to the 13th century C.E. (Common Era) and the “Machzor Vitry,” compiled by a French Talmudic scholar named Simhah ben Samuel.

The prayer can be offered for the well-being of a community, particularly for its leaders and machers (plural of “one who gets things done,” in Yiddish). It can be said to honor someone called up to the Torah, and for that person’s family, or for a bride and groom, or for a b’nai mitzvah. I found a mention of doctors and nurses reciting the Mi Sheberach in the operating theater.

There also is a Mi Sheberach for people who don’t talk during services. This effort to promote decorum during worship dates to the 17th century C.E., so kibbitzing (from the Yiddish “to offer gratuitous advice as an outsider”) may be as old as the service itself.

A version of the prayer recited in many non-Orthodox congregations translates to English as: “May the one who blessed our ancestors, Abraham, Isaac and Jacob, Sarah, Rebecca, Rachel and Leah, bless and heal those who are ill. May the Blessed Holy One be filled with compassion for their health to be restored and their strength to be revived. May God swiftly send them a complete renewal of body and spirit, and let us say, Amen.”

As recited by Orthodox Jews, the prayer for those who are ill begins: “May He who blessed our fathers, Abraham, Isaac and Jacob, Moses and Aaron, David and Solomon …” There is no mention of the matriarchs.

The phrase “complete renewal” (refuah shleimah, in Hebrew) may mean healing or cure, but also might mean bringing peace to someone with a terminal illness.

In some congregations the names of those for whom prayers are offered are said aloud (by congregants and/or the rabbi or cantor), in others they are said silently. Some congregations say the names in English. When Hebrew names are used to pray for someone ill, the mother’s name is added, as opposed to prayers in which a Hebrew name is followed by the father’s name.

While the research I did for this column did not change my disinclination to have my name said aloud, I do find myself less inclined to object when rabbis and friends say they will keep my name on their personal Mi Sheberach lists.

To them, all I can say is thank you.

comments