During Yom Kippur Afghanistan’s Jews Are Only a Memory

The last Jew in Afghanistan leaves the country to escape the new Taliban government.

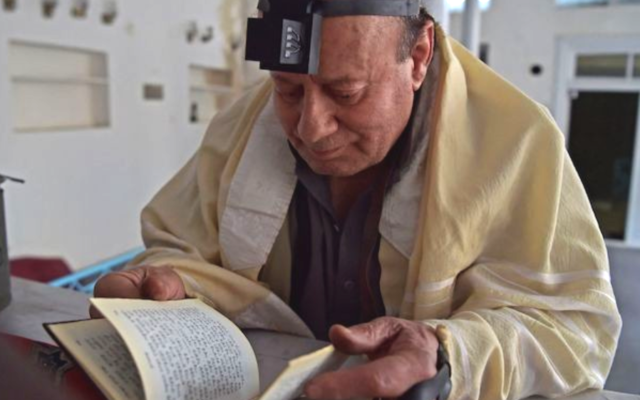

The last Jew has left Afghanistan. In a country that once hosted a thriving community of 40,000 members, Zebulon Simontov, a 62-year-old former restaurant owner and carpet dealer, is said to have made his way overland and out of the country. His wife and two daughters immigrated to Israel in 1998, but he stayed on as the caretaker of Kabul’s one remaining synagogue.

For the last 16 years, Simontov has been the Kabul synagogue’s sole resident, marking each holiday with a stubborn insistence on remaining in the country of his birth.

As he told Foreign Policy two years ago, he is “a man with no fear. I will never leave Afghanistan because of the Taliban or anyone else.”

Now, just before the High Holy Days, and with the urging of his friendly neighbors along Flower Street in Afghanistan’s capital, he accepted the help of Israeli-American businessman Moti Kahana to escape. Along with dozens of non-Jewish women and children, Simontov undertook a perilous five-day journey out of the country. Portions of the journey were broadcast on KAN, the state-owned Israeli television channel.

For hundreds, some say thousands of years, the Jews of Afghanistan survived repeated invasions, wars, riots, and religious persecution to create their distinctive Jewish communities along the Silk Road.

In recent years there has been a concerted effort to save the record of this people that, as tradition has it, descends from the ten lost tribes who vanished after the Assyrian invasion of Israel in 721 BCE.

A look at some of this history can be found in the pages of a rare volume, “Afghanistan: The Synagogue and the Jewish Home,” issued in an individually numbered edition of 500 copies by the Hebrew University in Jerusalem in 1991.

A copy of the book in Hebrew and English, numbered 177, is now in a private collection in Atlanta. It offers a glimpse of how Jewish life in such significant communities as Herat, near the Persian border, and Balkh, in the north of the country near Tajikistan in Central Asia, differed from the Ashkenazic or Sephardic world in Europe and America.

On the eve of Yom Kippur, as the catalog’s authors, Zohar Hanegbi and Bracha Yaniv describe it, Jews in the East and West differed dramatically in their customs.

While the Jews in Europe and America acknowledged their sins in the “Al Chet” prayer by gently tapping their chest, Jews in Afghanistan accounted for their mistakes by preparing for a ritual flogging.

After the evening service, each male over bar mitzvah age was required to receive 39 strokes on their back with a soft leather flogger while Psalm 78 was read. After that, the rabbi would issue a pardon for the individual’s sins.

While Jews in the West lit a pair of holiday tapers that might, at best, burn for an hour or two, Afghan Jews would light enormous candles they had created for each of their synagogues.

These candles were over six feet tall and often held in place by a copper or clay candle holder, or sham’dan.

The creation of the candles involved the entire community, which worked for more than a month under the supervision of local rabbis. High-quality wax was melted and gradually dripped around a braided cotton wick, made of six strands of cotton — one for each man to be called to the reading of the Torah on Yom Kippur.

It burned in the synagogue from the eve of Yom Kippur until prayers ended with the Ne’ilah service the following evening. Drops of the wax were said to be able to help cure the sick. In addition, the remains of the candle were used to make Havdalah candles for use in the synagogue and for Simchat Torah, when they lit the sanctuary for a night of dancing and song.

The catalogue contains almost 120 pages of photographs, including ornate marriage contracts from the 19th century, and handwritten and illustrated notebooks taken from Talmud study during the 1940s.

The book displays beautifully handcrafted ten-sided wooden Torah cases, bound with silk velvet, and crowns made up of three sets of metal finials. A malbush or scarf of hand-woven fabric is draped between the Torah’s ornaments.

Starting in the early 1950s, Jews began to leave Afghanistan in large numbers for Israel and America. By the time the Soviet Union invaded the country in 1979, they were almost all gone.

But they brought many of their ritual objects with them or had them shipped abroad. Elijah’s Chair, used during circumcision ceremonies, ended up in an Afghan synagogue in Bnei Brak in Israel. A pair of 19th century Torah scrolls found a new home in Queens in New York City.

A rare collection of religious documents, over a thousand years old, from an Afghani genizah, or synagogue depository, made their way to the National Library of Israel.

In Jerusalem, Tel Aviv, New York, London, and many other places, Afghani Jews made new homes out of old memories.

Now the last of Afghanistan’s Jews, Zebulon Simontov, has joined this community’s diaspora. The lights in his old synagogue home have been extinguished one final time.

comments