‘Hidden Heretics’ the Secret World of Ultra-Orthodox

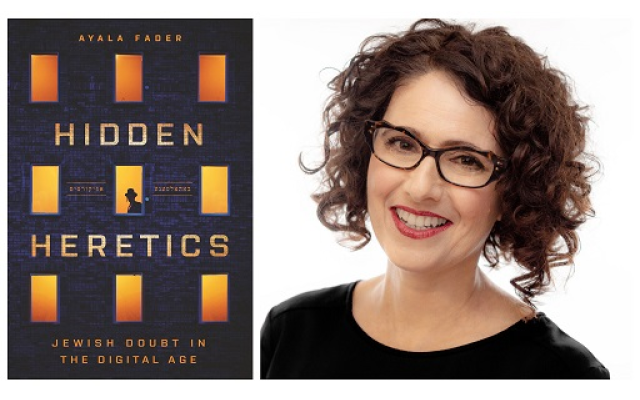

Emory University’s Tenenbaum Lecture was based on a book written by Ayala Fader, a Fordham University professor.

This year’s Tenenbaum Lecture at Emory University’s Tam Institute for Jewish Studies earlier this month presented a view of ultra-Orthodox life that few have been privileged to explore. It is the world of what anthropologist Ayala Fader, who teaches at Fordham University, calls “hidden heretics,” or those who have experienced what she describes as “life changing doubt.”

These are Jews, she found, who are mostly married and with children, who are imbedded in the deeply observant Hasidic communities in New York City. Nonetheless, they no longer believe in the basic religious dogma that form the spiritual backbone of their individual and communal lives. While they may still outwardly practice social and religious norms, privately, Fader said in her Tenenbaum Lecture, their doubts shape a very different approach to everyday Jewish life.

“It’s a kind of doubt that challenges the entire theological structure of extreme Jewish orthodoxy. This is life changing doubt that often leads people to disrupt or stop religious practice.”

Professor Fader’s study of hidden heretics was the subject of her book, of the same name, which was published in 2020 and was a finalist in the National Jewish Book Award and the Sami Rohr Prize for Jewish Literature. During her five years of research, she explored how men and women, often with large families of children and adolescents, navigated the difficulties that their choices about religious life presented to themselves and those close to them.

What makes “Hidden Heretics” different from recently popular books, films and other revelations of the ultra-observant Jewish lifestyle is that it does not portray these individuals fleeing from their families and the structured life they have led. They stay, to live out their lives surrounded by a system of belief they no longer accept.

Drawing back the curtain on this secret world, Fader describes how they live out their new lives, how they “secretly build relationships and fulfill their emerging dreams and desires,” as she describes it, despite the determined efforts of a network of rabbis and religiously observant therapists and life coaches who work to alter their behavior and their beliefs.

“Hidden heretics, also sometimes called ITC or In The Closet, are part of a broader 21st century generational crisis of authority among the ultra-Orthodox,” Fader believes. “Despite an increasingly robust demographic growth in that community, there have simultaneously been loud struggles over knowledge and truth. Hidden heretics pose dangerous questions in this context about who should have the authority for making individual life choices in the digital age?”

The book, which was written with the support of grants from the National Science Foundation and the National Foundation for the Humanities, also explores the role that computers and the Internet, as well as small, portable, smart cell phones, have played in helping to build an alternate community for those who have set themselves adrift from those around them.

It is what sets them apart, as this anthropologist of religion describes it from previous generations of the doubtful. The connections that the digital world offer allow these modern-day spiritual iconoclasts to build trust among themselves and to arrange clandestine meetings in a world which has generally been forbidden to them.

She followed them to their chat rooms and closed groups on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram. In the new virtual networks of friends that formed online, she also found that many had created a way to survive the depression and anxiety that often accompanied their new lives, particularly, when it came to living with a spouse who remained traditionally observant and children who maintained their belief.

“What all hidden heretics told me was that the Internet, particularly social media,” Fader told her Emory audience, “saved them from thinking that they were actually crazy, which is a common communal explanation. Or from thinking that they were alone in the world. These networks on social media and, later, in person create what I call a ‘heretical counter-public.’”

Whether these relatively small number of active non-believers can make a lasting difference in the largely insular and hierarchical world of black hats and caftans is not at all certain. But the movement, with the support of social media, Fader believes, is already making itself felt.

“I think they are actually changing their communities in interesting kinds of ways. There’s a new category that people call a Hasidic-lite or modern Hasidic, which is pushing back against some of the stringency while still embracing the esthetics of the ultra-Orthodox.”

- News

- Local

- Bob Bahr

- Tenenbaum Lecture

- Emory University’s Tam Institute for Jewish Studies

- Fordham University

- Ayala Fader

- Hasidic communities

- National Jewish Book Award

- Sami Rohr Prize for Jewish Literature.

- Hidden Heretics

- ITC or In The Closet

- National Science Foundation

- National Foundation for the Humanities

comments