Standing on Ground Sanctified by Lynching Victims

The National Memorial for Peace and Justice is a pilgrimage you must make if you care about a just future.

With my 9-year-old son, I recently visited the National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, Ala. The Equal Justice Initiative erected this powerful memorial to honor the victims of racially driven hatred and terror by lynchings, and it is worthy of pilgrimage.

We went because we know that to understand our country’s future, to have any hope of not repeating our mistakes, we have to know the foundation on which we stand.

We walked onto the grassy path of the memorial, immediately feeling the shift in energy and the power of standing on sacred ground.

Get The AJT Newsletter by email and never miss our top stories Free Sign Up

At first, the memorial markers seemed simple enough: rust-covered, rectangular columns etched with names. As we walked deeper into the memorial, my son began taking notice of the counties listed.

Instinctually, we began looking for Fulton County, where we live. More than 30 names were etched into the marker, making it one of the deadliest counties of the 800 where lynchings took place.

Allow this to sink in: Between 1877 and 1950, over 4,300 lynchings of African-American men, women and children were committed, mostly in the Southern states. Many were carried out by mobs in public squares in counties with established justice systems where no protection was offered to the victims.

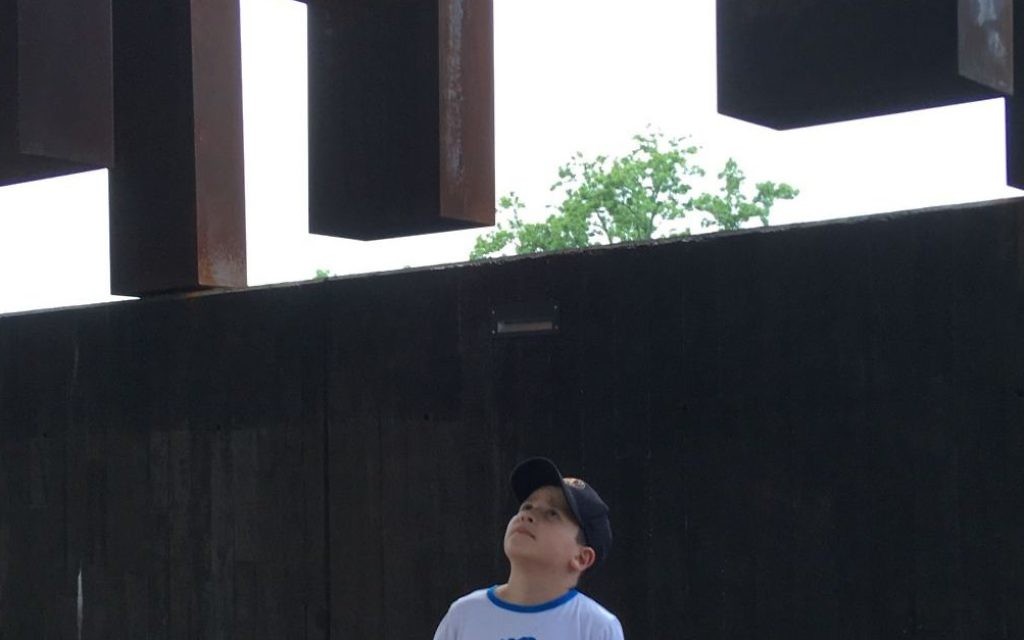

The farther into the memorial we got, the more gravitational pull we could feel as the columns’ orientation began to shift upward. At the center of the memorial, we found ourselves below the columns, looking up.

Gravity never felt so heavy. Here we bore witness to the tragedy of it all. Here we stood in silence.

I felt grateful when a young man named William, a docent from the Equal Justice Initiative, came up to my son to check in with him and get him to talk. He thanked us for coming and explained that the memorial has a dual purpose: to honor the dead and to educate the living. He pointed out what looked like a graveyard adjacent to the memorial.

I felt grateful when a young man named William, a docent from the Equal Justice Initiative, came up to my son to check in with him and get him to talk. He thanked us for coming and explained that the memorial has a dual purpose: to honor the dead and to educate the living. He pointed out what looked like a graveyard adjacent to the memorial.

Columns, identical to those hanging in the memorial, were laid flat on a grassy knoll. The hope is that the listed counties will claim each of the marker columns and display them in their public spaces. As each county claims a column, a garden will be planted in its stead. So far, only one marker has been claimed out of 800.

Jews, as a people whose mission it is to honor our dead and to educate the living, know the significance of reckoning with the past. We know that the broken places do not heal until we tend to the wounds. We know that it takes generations to reclaim the narrative of trauma and lift the voices of the voiceless. We know the significance of making records and standing up to deniers.

If you care about the rise of white supremacy in America, you have to be willing to go back in American history to see the ideological legacy of slavery and its aftermath. If the neo-Nazi marches in Charlottesville, Va., kept you up at night, tossing and worrying about our country’s future, you have to be willing to see it not as a nascent movement, but as an age-old American problem.

If you are following the statistics recorded by the Anti-Defamation League about the rise of anti-Semitism, you have to be willing to look closely at the deadly reality of racial profiling by law enforcement and all forms of discrimination. If you worry about the recent survey conducted by the Conference on Jewish Material Claims Against Germany that revealed a fifth of American millennials have no knowledge of the Holocaust, you must ask yourself how much you know about the practice of extrajudicial killings and public lynchings of African-Americans in this country.

If you are following the statistics recorded by the Anti-Defamation League about the rise of anti-Semitism, you have to be willing to look closely at the deadly reality of racial profiling by law enforcement and all forms of discrimination. If you worry about the recent survey conducted by the Conference on Jewish Material Claims Against Germany that revealed a fifth of American millennials have no knowledge of the Holocaust, you must ask yourself how much you know about the practice of extrajudicial killings and public lynchings of African-Americans in this country.

If all this makes you uncomfortable, it is probably not an unfamiliar feeling, as Jews have plenty of experience with owning and safeguarding the painful parts of our history. We know the damage of having our history denied. It feels suffocating to face other people’s doubt, negligence and apathy. So let us not be deterred by discomfort.

As we walked away, my son said, “We have a choice. We either live in a world of graveyards or in a world of gardens.”

Let us make sure our counties claim their memorial markers and the history that belongs to all of us now. Let us know our country’s history so that we can protest the injustices of our present and demand a different future.

comments