Terezin Teens Fought Back with Underground Magazine

Curated by Rina Taraseiskey, granddaughter of Holocaust survivors, "Vedem Undeground" is at The William Breman Jewish Heritage Museum in Midtown.

One of the largest attendances of any member exhibit at the William Breman Jewish Heritage Museum was Oct. 15, highlighting a story of a magazine produced in the Holocaust by teenage boys.

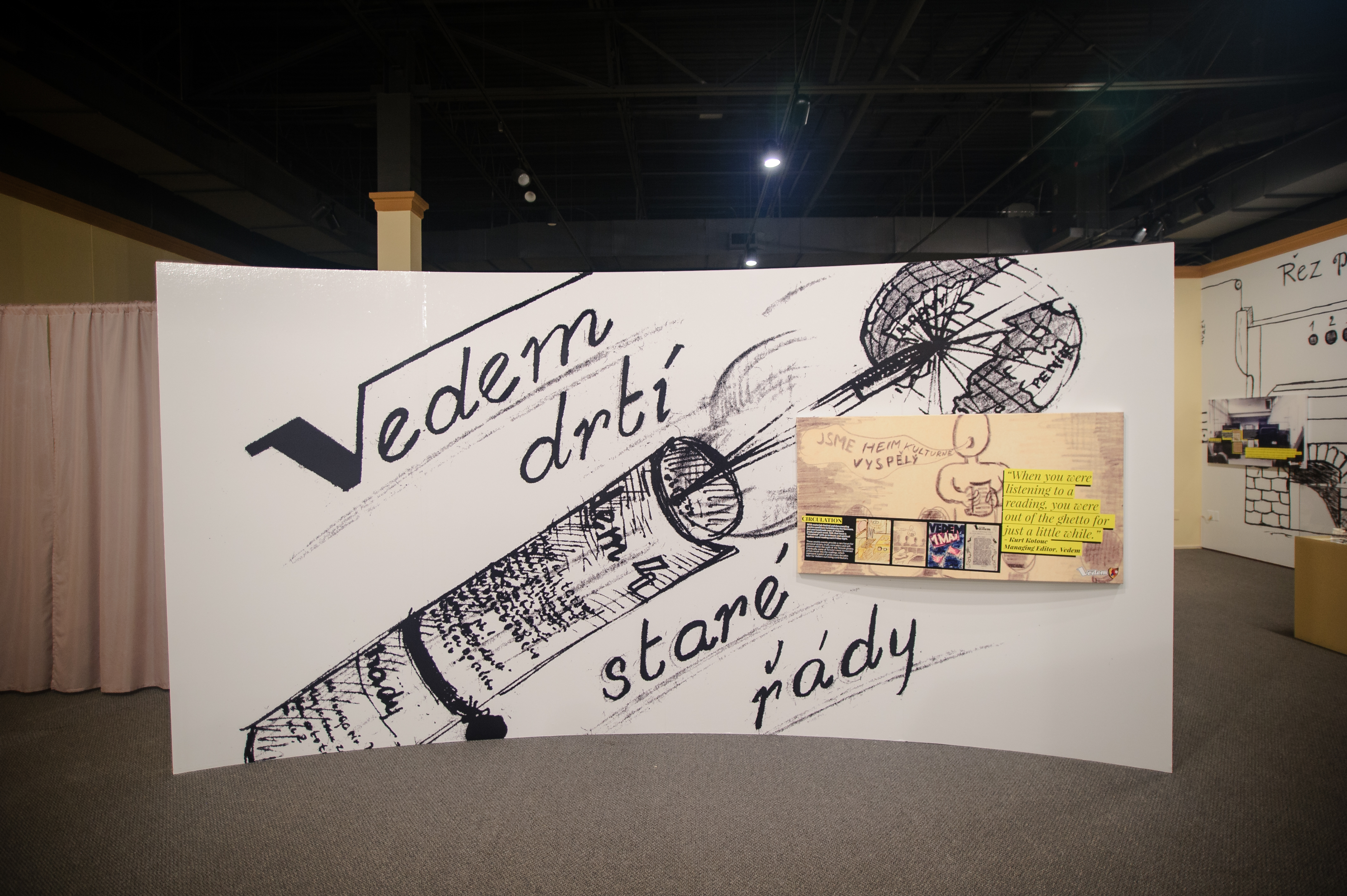

“Vedem Underground: The Secret Magazine of the Terezin Ghetto (1942-1944),” sheds light on the lives of children of the transport camp, a stop on the way to the death camps.

One of them was Petr Ginz, sent to Terezin alone, while his family stayed behind. An artistic prodigy, he wrote a diary, five novels and stories before turning 14. He was also the creator, editor and driving force behind Vedem, a weekly underground magazine he and other teenage boys who were prisoners in the Nazi camp painstakingly produced.

“Vedem shows the world that we did fight back,” said Leo Lowy, a Vedem writer and one of the few Auschwitz survivors. The word vedem means “in the lead” in Czech, and the magazine was a symbol of protest, rebellion and creative activism.

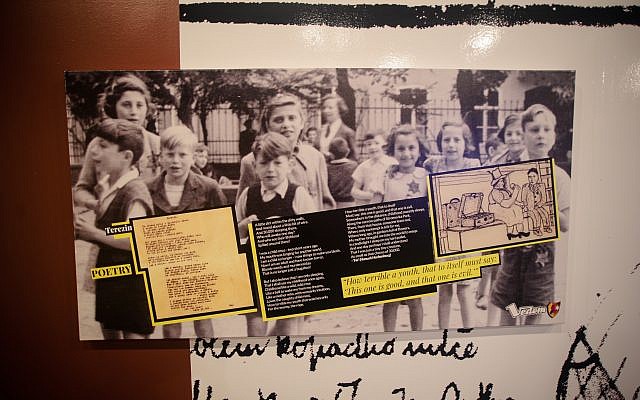

The exhibition features pop-art graphics, prose and poetry, creating a contemporary version of a magazine unlike what we read today. The display celebrates the artistic and cultural legacy of the boys who ultimately produced 83 issues.

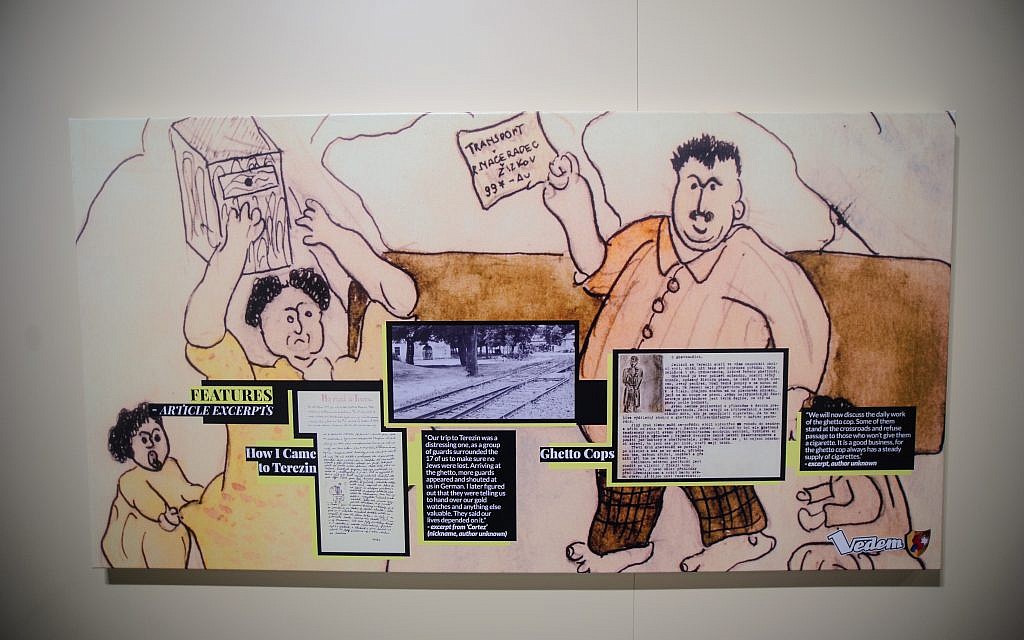

To paint the pictures and write the articles of Vedem, the boys smuggled in supplies from the offices at the ghetto. They found an abandoned typewriter in an old office in the converted schoolhouse in which they lived and used it to produce their magazine. The boys created the issues in secret throughout the week on the wooden table in the middle of the bunkroom, or while sitting on their bunks. Each boy in the group contributed drawings, articles, poems, thoughts or interviews.

They had nicknames to keep their identities from the Nazis. One boy would be on the lookout. If a guard approached, he gave a secret signal to warn the others, and the boys hid everything.

After 30 issues, the typewriter ran out of ink, so the boys wrote the next 53 issues by hand. They never gave up, no matter what obstacles they faced, and leaned on each other for support and comfort. Each week, they created only one handmade issue because there were no resources to make copies.

Out of the 92 boys who passed through Home #1, the cellblock where the Vedem boys lived, only 15 survived the Holocaust. Ginz, the magazine creator, was not one of them. He died at 16 in Auschwitz.

Rina Taraseiskey’s grandparents were Holocaust survivors. She curated the exhibition.

“It has been an honor to showcase the incredibly courageous and creative work by some of the youngest resistance fighters of the World War era,” she said. “These teenage boys refused to give up their identity, their humanity and their fighting spirit.”

Danny King, Vedem Underground co-producer, reiterated how the boys risked their lives to produce the magazine. “Vedem reflected the stark reality of life inside Terezin, but it was also an escape for them. They expressed their opinions with humor, cartoons and poetry. They could forget that they were in prison.”

The magazine collection included one copy each of 800 pages produced. They were buried in a metal box and later retrieved by a Vedem writer who survived life in the ghetto.

“Vedem Underground: The Secret Magazine of the Terezin Ghetto (1942-1944)” will be on view at the Breman Museum, 1440 Spring St. NW, Atlanta, through March 10, 2019.

comments