The Covenant of Hope

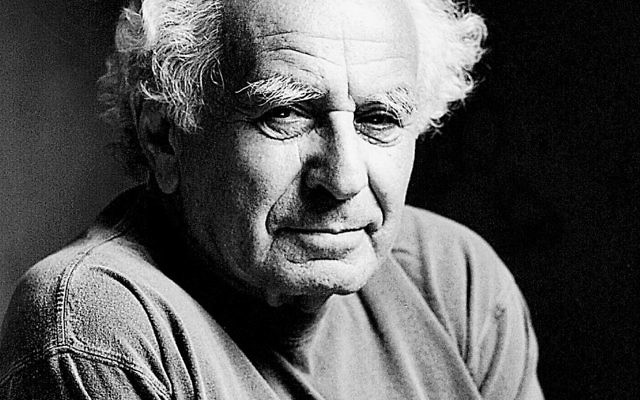

Holocaust survivor Eugen Schoenfeld reflects on an infamous train ride, which was the backdrop of a hopeful event.

Eugen Schoenfeld was born November 8, 1925. He is the oldest son of a book store owner in a small town in Czechoslovakia and a holocaust survivor.

Some time in my preteen years, my maternal grandmother called me while I was playing in the courtyard “Naftuli, come inside.” I cannot recall what precipitated the occasion, why she seemed eager to talk to me. But, after a while she proceeded to instruct me in another Yiddish adage. She was fond of adages and proverbs. In this instance she taught me the following dictum: “gelt verloyren, gurnisht verloyren; hofenung verloyren aless is verloyren.” Meaning: Money lost, nothing is lost; hope lost all is lost.

Now at 93, with advanced heart failure and struggling for my breath, what is left to me is hope for a few more years and for a pleasant old age, and above all, for a peaceful world.

Of course, hope is what sustained us Jews during the two millennia of diaspora.

Were it not for the hope of the coming of the Messiah, the hope of returning to our erstwhile country life would have been lost and most likely, we probably could not have endured such conditions and Judaism would have not survived. Hence our commitment to the idea of tikvah [hope] to gather us from the four corners of the world and bring us erect and proud to our land. (Emphasis added).

No wonder that Zionism was founded on hope, as it is expressed in Israel’s national anthem, written a century before this dream of an independent Jewish country was realized. The “Hatikvah,” the expression of our old hope to return to Zion and Jerusalem, was central to our life since the Babylonian exile.

Our emphasis on the essentiality of hope in life was and is especially important to those of us who experienced the Holocaust and those of us who endured post Holocaust difficulties. Unlike Dante Alighieri’s statement written on the entrance to hell: “Abandon all hope ye who enter here” was and is an anathema to us. It was precisely in this hell-hole, the Holocaust, when hope was most needed, and indeed it was that human ideal that kept us, at least me, alive.

Would the Israeli heroes, who battled overwhelming odds to keep Israel, this new Jewish national home, alive and striving, if it were not for “our ancient hope” given to us by G-d?

Hope is, at least to me, the third covenant that we have with G-d. We all are aware of our covenant with G-d through Abraham. We know about our covenant with G-d forged at Sinai. But after reading Jeremiah, at least from my perspective, it seems that we have a third covenant – the covenant of hope.

Every year I read Jeremiah’s pronouncement in Chapter 31, namely, his promise of G-d’s gift of hope that He extended to Rachel, our quintessential matriarch, and through her to us Jews. The time when this occurred was 605 B.C.E., the years when our ancestors were being taken into Babylonian captivity. Jeremiah watches this scene from the high ground as the best of our people are driven out of our homeland, and does not see a future for her children. Finally, G-d speaks to her and commands her “keep your voice from crying, and your eyes from shedding tears, for there is reward to your efforts, there is hope for your progenies and they shall return from the enemy’s land and they shall live within their borders.”

Some time at the end of April 1944, after a stay in Birkenau, some of us, including members of my family, were sent to Warsaw to work on a project of rebuilding Berlin. There in the camps where people were subject to inhuman treatment, hopelessness could easily have become the dominant perspective. And yet, it was there that I was subject to an extraordinary experience that led me to reject negativism and become subject to hope.

To get from Birkenau death camp with its gas chambers and crematoria to Warsaw, we once again embarked the infamous trains on our way to Poland’s former capital. The 50 or so inmates in the freight car were guarded by two SS, and, in our case, one was a short Ukrainian-turned-Nazi who constantly threatened us with his gun. The other guard could have been a poster image of Hitler’s ideal of an Aryan about 6-foot-2, blue-eyed and blond. Every time the Ukrainian would threaten us, he spoke harshly to him and told us not to fear, that nothing would happen to us. But my greatest surprise came when the train stopped at a station. The German guard left us to reappear a half-hour later loaded down with containers filled with coffee.

Can you imagine that here in the midst of hatred, and of death, there was one righteous man, and in spite of being an SS, he was able to empathize with us and our condition? Should he have done these two acts, it would have been sufficient to call him righteous, but he went one step further. That same afternoon, the train stopped at another station, and as usual, he gathered all the pots and pans and came back in a half-an-hour, but before he gave anything, he profoundly apologized. He told us how sorry he was that he couldn’t bring us a hot drink because coffee seems to be available only before noon – the best he could do was to bring us water.

It was this event that reinforced in me a hope for the future. If an SS could become this concerned about us, surely there is hope to believe in the perfectibility of the human race – that is the ultimate of action of a person committed to tikkun olam [repairing the world]. I believe that such action brings about the idea of world and individual perfection that the prophets’ vision of the Messianic period that they called achrit hyamim [end of days] would be brought about.

comments