Simchat Torah in the USA After WWII

Until the 1950s the holiday was a part of the Jewish men’s preserve. As the participatory rights of women grew, Simchat Torah changed at Reform and Conservative services.

In the 19th century, the initial references to Simchat Torah in the USA were from New York, Boston, Chicago and Philadelphia, but as the Jewish population grew in the western sector of North America, the joyous holiday was celebrated there as well.

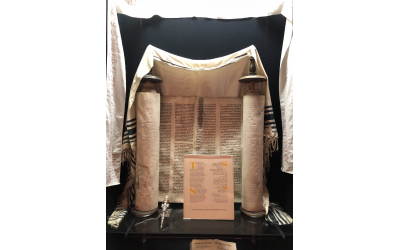

This story appeared in the San Francisco Call newspaper Oct. 5, 1879: “On Simchat Torah, all the sephorim, scrolls of the law, were taken out of the Ark, curled in procession around the synagogue.”

In Atlanta, my uncle, Rabbi Samuel Geffen (z’’l), had the Shearith Israel religious school kids primed to sing “Sisu V’ Simchu B’ Simchas Torah” on the eve of the holiday 1936, for the first time over WSB radio.

Get The AJT Newsletter by email and never miss our top stories Free Sign Up

While the country had weathered a depression, Geffen’s Simchat Torah celebrations were so innovative each year, they influenced 60 new families to affiliate with Shearith Israel by 1936.

As he left to study for ordination, the Southern Israelite weekly Anglo-Jewish paper, noted: “Samuel Geffen is a very talented educator. The children increased their Judaic knowledge through classes, organized assemblies for each holiday, and performances of Hebrew and Yiddish songs on WSB radio. We wish Mr. Geffen well; it is certain he will be a real success in the Judaic field.”

The observance of Simchat Torah in synagogues rose in the 20s and 30s in the USA. Then the catastrophic Holocaust pushed the holiday into the background.

“Now that the war is over,” Rabbi Hyman Friedman noted in January 1946, “the most enthusiastic celebration of Simchat Torah and other holidays will again be possible. When the time comes, we should all get our dancing shoes ready.”

Simchat Torah can be characterized as the holiday that was not supposed to be. In the second Temple period, the Torah text was followed: Just one day of observance at the end of Sukkot, Shemini Atzeret. The day after that began as Isru Chag (bind the holiday) and ultimately earned the name Simchat Torah for the manner in which joy and Torah were combined.

Until the 1950s the holiday was a part of the Jewish men’s preserve. As the participatory rights of women grew, Simchat Torah offered the opportunity for innovative additions in the services at the Reform and Conservative synagogues.

Rabbi Stuart Geller of Jerusalem, a Reform rabbi in USA before retiring and making aliyah 14 years ago, offers a description of what a standard ritual was like in many synagogues like his: “The major observance of the chag in our Reform Temple on Long Island was on erev Simchat Torah. At the service we completed the reading of the Torah and then began with Bereshit. However, people did come to the morning service because we chanted the Yizkor prayer for loved ones.”

Geller notes further: “The scrolls were paraded around the synagogue for one hakafah, and then we marched out the doors into the street. The police were accommodating by blocking off the area around us from moving traffic. About 500 people were present; the volunteer choir sang many songs, sometimes using world-famous melodies with Hebrew inserted into them.”

He explains what happens next: “The many scrolls were returned to the ark of the synagogue; just one remained outside. We carefully unrolled it, giving adults a chance to hold the scroll and listen to sections read. Of course, we finished Devarim and started with Bereshit. Then the Torah scroll was rolled up and there was much Israeli-style dancing, starring the children who formed a long line for ‘Yesh Lanu Tayish.’”

Food was there too. “Finally, back into the ballroom for an elaborate Kiddish. I stood in the sukkah for everyone who wanted to bench lulav, usually about a hundred people.”

What was fascinating in the 60s, 70s and 80s was how the spirit of Simchat Torah was used to bring more American Jews into the battle, forcing the former Soviet Union to liberate Jews held behind the Iron Curtain and permit them to go to Israel or other countries. Certain individuals in the United States, in particular the Lubavitcher Rebbe and Rabbi Pinchas Teitz, had been secretly sending tallitot, tefillin and siddurim to the refuseniks who so wanted to practice their Judaism openly.

When Golda Meir was in New York for Simchat Torah in October 1969, she spoke movingly before the United Jewish Appeal and other national agencies, giving an “overwhelming tribute” to these forgotten Jews. She labeled Simchat Torah as an International Day of Solidarity and called on all the Jews in the USA and throughout the world to stand up and be counted in this “war.”

The following year, with a great deal of planning, Rabbi Haskel Lookstein and his wife appeared in Moscow for Simchat Torah. With much help from refuseniks and the American embassy, Lookstein assembled thousands of Soviet Jews outside the main synagogue of Moscow and led them in singing and dancing.

During Chol HaMoed Sukkot in 1971 a Simchat Torah Freedom Procession marched to the Soviet Mission in Glen Cove, Long Island. As the New York Times reported, “100 Torah scrolls were carried; Hebrew songs were sung with gusto; freedom slogans were shouted over and over.”

On Oct. 12, 1971, Simchat Torah itself, 10,000 Jews in New York marched. The hakafot created tremendous energy in “publicizing their concern for the plight of Russian Jews.”

In 1974, Simchat Torah, Oct. 4, witnessed rallies in 50 American cities: New York, Chicago, Dallas, St. Louis, Philadelphia and many more, to intensify the campaign to free Soviet Jews. From then on, year after year, the holiday rallies grew and grew, until 1988 when the doors were opened.

My wife, Rita, and I were in the former Soviet Union in August 1988, visiting refuseniks in little towns like Bendery. At the hotel where we stayed in Kiev, we witnessed the first visit by Israelis who had parents and siblings living in the Ukraine.

Certainly, the growing interest in the hatan Torah, hatan Bereshit, and the kalat Torah and kalat Bereshit raised those annual Simchat Torah honors to a higher level. Honoring sisterhood and brotherhood presidents as the kalot and hatanim infused Simchat Torah with an aura never previously seen.

The energy of women who have become a dynamic part of the Simchat Torah celebrations is found in Rabbis Jill Jacobs and Jill Hammer. Jacobs once wrote, “The image of ‘dancing in the face of darkness’ as Jewish women became liberated on Simchat Torah meant much to me because in my synagogue we burst out into the chilling fall night air dancing with the Sifrei Torah. As we danced, we were fortified with strength and energy for the challenges ahead.”

In her guide and commentary to Simchat Torah, Rabbi Hammer wrote, “I have never in my adult life missed Simchat Torah. I have danced with the Torah in student chapels, in formal synagogues, in the seminaries and in the streets of New York and Boston.” Then she stressed how important the holiday has been to her.

“To join a dance circle, I have run down 40 or more stairs. I have crept through crowds to make sure I was dancing. Simchat Torah is the holiday I look forward to all year … not only because of its celebration of joy, motion and music, but because it’s a celebration of G-d as changemaker. For me, Simchat Torah celebrates the possibility of rereading the Torah in a new light.”

comments