Judaism Inspired Schwartz’s Pursuit of Justice

The attorney was known to say, “We don’t help individuals in need because they are Jews. We help people in need because WE are Jews.”

Dave Schechter is a veteran journalist whose career includes writing and producing reports from Israel and elsewhere in the Middle East.

“It is not your duty to complete the work. Nor are you free to desist from it.” (Pirke Avot)

Dale Marvin Schwartz did his duty and left a legacy for those who continue the work.

The attorney praised for his advocacy on behalf of immigrants, in support of civil rights, and to clear the name of Leo Frank, died Aug. 27, one week after his 79th birthday.

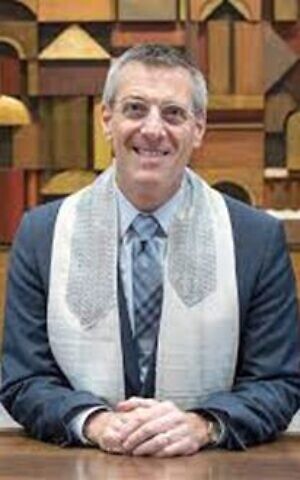

Schwartz was “a giant in the Atlanta Jewish community,” said Temple Kol Emeth Rabbi Emeritus Steve Lebow, who worked with him on the Frank case. Schwartz’s communal credits included leadership roles on the boards of the Jewish Federation of Greater Atlanta, Jewish Family & Career Services of Atlanta, the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society, and the Anti-Defamation League.

Judaism was integral to his life and work.

“Dale lived and breathed tikkun olam daily. Countless immigrants, law students, legal colleagues, and victims of prejudice and bigotry benefited from Dale’s generosity of wisdom and relentless pursuit of justice. Underneath his easy-going, gregarious exterior was a man who worked incredibly long hours. He had a positive impact on more lives daily than others accomplish in a life-time,” said Lauren Levin, a former ADL colleague who credits Schwartz with inspiring her to become an immigration attorney.

Schwartz’s father operated a clothing store in Winder, Ga., where, despite threats, he hired and served African Americans as customers. “I think that is prescient and symbolic and emblematic of where Dale came from and what he did with his own life,” Lebow said.

Schwartz eventually received bachelors and law degrees from the University of Georgia, but in February 1960 he was a Vanderbilt University freshman and a pledge for the Alpha Epsilon Pi fraternity. Responding to a telephoned request from an African American student at Fisk University, Schwartz and other AEPi members turned out to support students from Black colleges who were holding sit-ins to desegregate the Woolworth store lunch counter in downtown Nashville.

In a 2020 article for the AEPi magazine, Schwartz recounted: “The waitresses were prepared and put up a CLOSED sign on the lunch counter. One of the waitresses poured a vanilla milkshake over the head of one of the students, turned around, and left. A few minutes later the Nashville police arrived. They mocked me and my Brothers and called us ‘N****r Lovers.’ … One short, fat white man walked up to the back of one of the young women sitting at the counter and put his lighted cigar into her back.”

“We jumped that man and beat him up,” Schwartz wrote. “But the Klan types turned their full attention to beating us kids. I got hurt so badly that I was taken to Vanderbilt Hospital’s ER for treatment. The local policemen stood by, doing nothing to stop the beatings, and just laughed at us. Luckily, nothing on me was broken. My mother and father got to see me being beaten on the national network news that evening, as photographed by the local TV stations, which arrived shortly after the rednecks. The university threatened to kick us AEPi Brothers out of school for ‘inciting a riot.’ We dared them to do that, and they backed down.”

That incident came full circle 30 years later, when Schwartz’s law firm purchased a table at a birthday party and fundraiser for Congressman John Lewis at a downtown Atlanta hotel. A video of Lewis’ life was shown. “They found an old black and white film clip from one of the networks, and there I was, for all of two seconds on the screen, being beaten up. My wife let out a scream when she saw me, and John Lewis, who was sitting a few tables away from us, came right over to ask my wife what was wrong. When she told him, he asked us to stay after dinner ended,” Schwartz wrote.

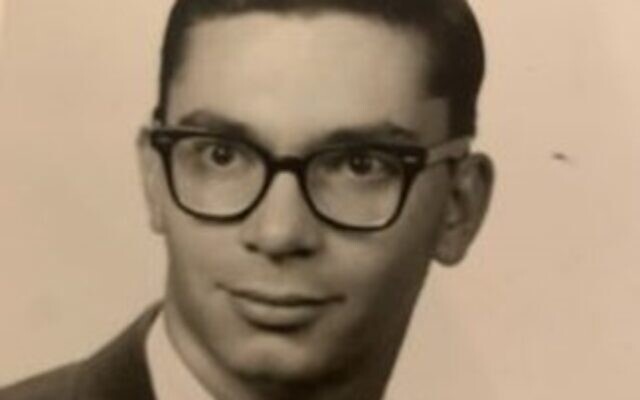

Lewis asked the video technician to replay the video “and stop on the frame when my face appeared, replete with my pompadour and big, black Buddy Holly glasses. John hugged me and remarked that we had known each other for more than 30 years, but never realized we were together at that lunch counter in Nashville,” Schwartz recalled.

“John looked at me and my wife and said, ‘Every Black politician in America claims he was at that lunch counter in Nashville, but I’m the only one with a white witness.’ I will never forget that moment,” he recalled.

When President Barack Obama mentioned the Nashville sit-in during his July 2020 eulogy for Lewis, “It made me remember this story and reminisce how, when John and I were together over the years, he mentioned to me that he would never forget how we Jews, and especially Jewish kids (and AEPi men), were the only ones they could turn to for support and help in those early days. I am proud that my AEPi Brothers joined me that day. None of us will ever forget that day, or the reasons we were there,” Schwartz wrote.

Schwartz served as lead counsel in the effort to seek a pardon for Frank, the Jewish manager of a pencil factory in downtown Atlanta, who was convicted in 1913 of murder in the death of a 13-year-old employee, Mary Phagan. After Gov. John Slaton commuted his death sentence to life in prison, a group of Cobb County men, including prominent figures in Marietta — Phagan’s hometown — plotted and kidnapped Frank from the penitentiary in Milledgeville. They drove Frank to a Marietta woods, near what today is Frey’s Gin Road, and before dawn on Aug. 17, 1915, lynched him.

Schwartz described the pardon effort as being “like Sisyphus pushing that rock up a hill.” That rock included Atlanta’s own Jewish community. Schwartz recalled a meeting of 300-400 people at the Jewish Community Center at which the ADL, American Jewish Committee and the Jewish Federation of Atlanta — the organizations behind the appeal — were urged to leave the past alone. “People begged us not to do it,” he said in an interview several years ago.

In 1983, the Georgia State Board of Pardons and Paroles rejected a pardon application filed after 85-year-old Alonzo Mann told The Tennessean newspaper what he had witnessed while working at the factory on April 26, 1913, the day Phagan was murdered. Schwartz said Mann told him about anti-Jewish epithets shouted outside the courthouse during the 1913 trial. The state board determined that “it is impossible to decide conclusively the guilt or innocence of Frank.”

Three years later, Schwartz and his colleagues made, in his words, “not a legal argument so much as a political or emotional plea.” In granting that application, the board said it acted “without attempting to address the question of guilt or innocence and in recognition of the state’s failure to protect the person of Leo M. Frank and thereby preserve his opportunity for continued legal appeal of his conviction, and in recognition of the state’s failure to bring his killers to justice.”

Before the 30th anniversary of the pardon, Schwartz told the AJT, “I remember the great joy I felt when I got news of the pardon’s having been granted! We had worked on this case for over five years. I remember thinking that the Anti-Defamation League could finally close its case No. 001 after over 70 years. … I recalled the opening words of the brief written by Charles Wittenstein and me: Justice, Justice, Shalt You Pursue.”

Lebow said that in recent days he, Schwartz, and former Gov. Roy Barnes “were still working on a strategy to get Leo Frank exonerated.”

For his birthday this year, Schwartz sought donations to HIAS. When elected its board chair in 2013, Schwartz said, “HIAS is in my blood, part of my DNA. Not just because HIAS brought to America three of my grandparents and helped them establish new lives here, but because of the millions of other people – Jews and non-Jews – whom HIAS has rescued or resettled. To be a part of that effort – even in a small way – is both an honor and a precious gift from above.”

In a eulogy delivered at the funeral, HIAS President and CEO Mark Hetfield quoted Schwartz’s response to critics of the organization’s mission, which extends beyond the Jewish world: “We don’t help individuals in need because they are Jews. We help people in need because WE are Jews.”

Speaking of his long-time congregant, Temple Sinai Rabbi Ron Segal told the AJT: “Throughout his entire life, both professionally as well as through his active volunteerism, Dale tirelessly and boldly worked to establish laws ensuring the just and equitable treatment of every individual. He made an impression upon everyone he met, as well as an enduring difference in the world he left behind, and he will be dearly missed.”

- Dave Schechter

- News

- Local

- Dale Marvin Schwartz

- Leo M. Frank

- Steve Lebow

- Lauren Levin

- Mary Phagan

- Representative John Lewis

- Gov. Roy Barnes

- Charles Wittenstein

- Alonzo Mann

- Gov. John M. Slaton

- President Barack Obama

- Rabbi Ron Segal

- Mark Hetfield

- Cobb County

- Civil Rights

- Nashville

- Woolworth

- sit-in

- Lynching

- 1915

- marietta

- Milledgeville

- Tikkun Olam

- Justice

- Winder

- Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society

- Alpha Epsilon Pi

- Temple Kol Emeth

- Anti-Defamation League

- University of Georgia

- Jewish Federation of Atlanta

- Fisk University

- American Jewish Committee

- Georgia State Board of Pardons and Paroles

comments